Lord, Open Our Lips: Reclaiming the Daily Office in The Episcopal Church

By: The Rev. Marshall A. Jolly

A short fifteen-minute drive north from downtown Cincinnati, in the quiet suburban Ohio neighborhood of Glendale, is the Community of the Transfiguration. “The Community” is an Episcopal order of consecrated religious women living together in community under the traditional vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Enclosed within an eight-foot-tall stone wall is The Community’s convent, retreat center, school, and the Chapel of the Transfiguration—an English country-style stone church with an elaborate wood-carved quire, marble high altar, and an impressive pipe organ. Since its founding in 1898, The Community has educated thousands of children in its school, cared for hundreds of ailing people in a nursing home run by its sisters, and has served as a wellspring of spiritual nourishment for countless people seeking rest, refreshment, and space for discernment. Since my ordination to the priesthood in 2012, I too have made annual retreats at The Community.

The rhythm underpinning everything that happens in The Community is soaked in and shaped by prayer. Whereas much of my own life is an effort to try and fit the sacred moments in and among secular demands, the Community operated in reverse—or, perhaps, in proper order. Here, the secular demands are worked in among the sacred discipline of prayer. The Community stands as both a witness to the Blessed Apostle’s admonition to “pray without ceasing,”[1] and a portal through which the faithful are brought into communion with an ancient tradition and discipline of daily liturgical prayer.

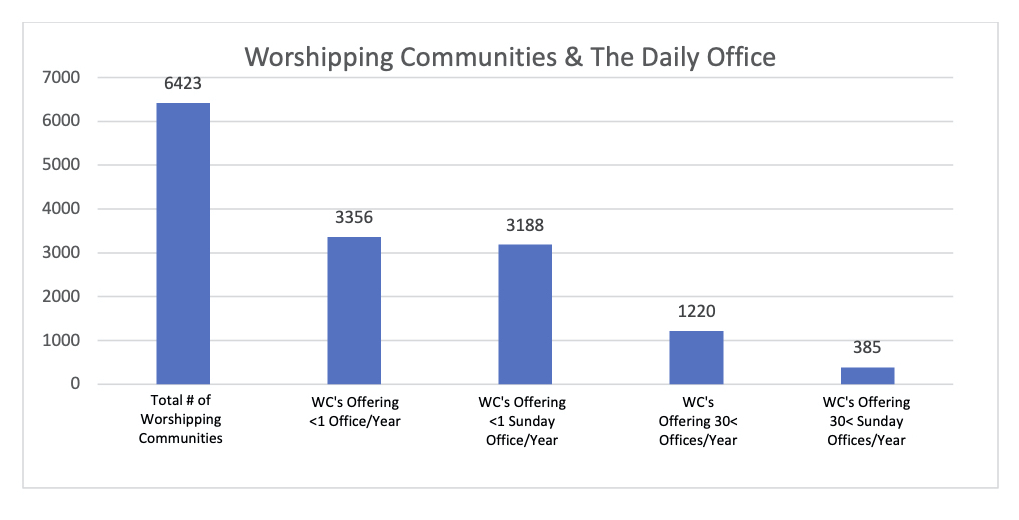

However, in recent years—especially following the adoption of the 1979 edition of the Book of Common Prayer—devotion to the Daily Office has diminished. As recently as 2017, The Episcopal Church’s Office of Research and Statistics reported that fewer than half (49%) of all Episcopal parishes offer the Daily Office on Sundays at all.[2] In terms of a regular* practice, the statistic is even starker: Only 19% of all worshipping communities offer regular service of the Daily Office, and only 6%–fewer than 400 worshipping communities—offer a regular service of the Daily Office on Sundays.[3]

One possible explanation for this shift can be found in the liturgical emphasis of the 1979 prayer book. In the preface of the prayer book, entitled, “Concerning the Service of the Church,” the first sentence reads, “The Holy Eucharist, the principal act of Christian worship on the Lord’s Day and other major Feasts, and Daily Morning and Evening Prayer, as set forth in this Book, are the regular services appointed for public worship in this Church.”[1] While close and complementary association between the Eucharist and the Office may have been the prayer book’s intention, in practice, directing that the Eucharist be the principal act of Christian worship on the Lord’s Day has created a de facto hierarchy, where Eucharist is primary and normative, and the Daily Office is secondary and subordinate.

One possible explanation for this shift can be found in the liturgical emphasis of the 1979 prayer book. In the preface of the prayer book, entitled, “Concerning the Service of the Church,” the first sentence reads, “The Holy Eucharist, the principal act of Christian worship on the Lord’s Day and other major Feasts, and Daily Morning and Evening Prayer, as set forth in this Book, are the regular services appointed for public worship in this Church.”[1] While close and complementary association between the Eucharist and the Office may have been the prayer book’s intention, in practice, directing that the Eucharist be the principal act of Christian worship on the Lord’s Day has created a de facto hierarchy, where Eucharist is primary and normative, and the Daily Office is secondary and subordinate.

This project asks how The Episcopal Church might begin to reclaim the gift and heritage of the Daily Office as a regular part of its worship by examining my own ministry setting as a case study.

Like nearly 75% of all Episcopal churches, Grace Episcopal Church in Morganton, North Carolina has an average Sunday attendance of fewer than 100 people. I am the only full-time staff member, and the only stipendiary clergyperson serving the congregation.+ We are a thoroughly Eucharist-centered parish. In 2018, for example, 204 services of public worship were conducted. Of those 204 services, 184 were services of Holy Eucharist, and the remaining 20 were from the Daily Office. Given the limitations of time, priorities, and staffing, what strategies and practices could I employ in order to introduce my parish to the Daily Office, with an eye toward establishing a regular practice?

I began by asking my parish to complete a 10-question survey, which was distributed online and in person over a period of approximately three weeks. The survey helped establish a baseline by answering four broad questions: How and how often do my parishioners pray? What are the barriers to their prayer? Why do they pray? How can Grace Episcopal Church serve as a resource for enhancing the prayer life of its parishioners?

The survey revealed important and somewhat surprising findings. I discovered that although our communal liturgical life underemphasizes the Daily Office, more than 10% of respondents noted that they included at least one of the Daily Offices in their prayer practice—many of them noted specifically praying Compline. Furthermore, 11% noted incorporating the daily devotional Forward Day By Day, which is purchased and made available by Grace Episcopal Church, as part of their prayer practice.

I was also interested in learning how and why my parishioners prayed, and so I asked them to describe it in their own words. One parishioner’s comments illustrated a trend: “[My prayer life is] sporadic. I don’t think what I do could actually be called a practice. It’s more like random prayer…” 75% of respondents indicated that at least a portion of their prayer life had no discernable form. A further 34% of respondents noted that meditation and centering prayer were components of their prayer practice.

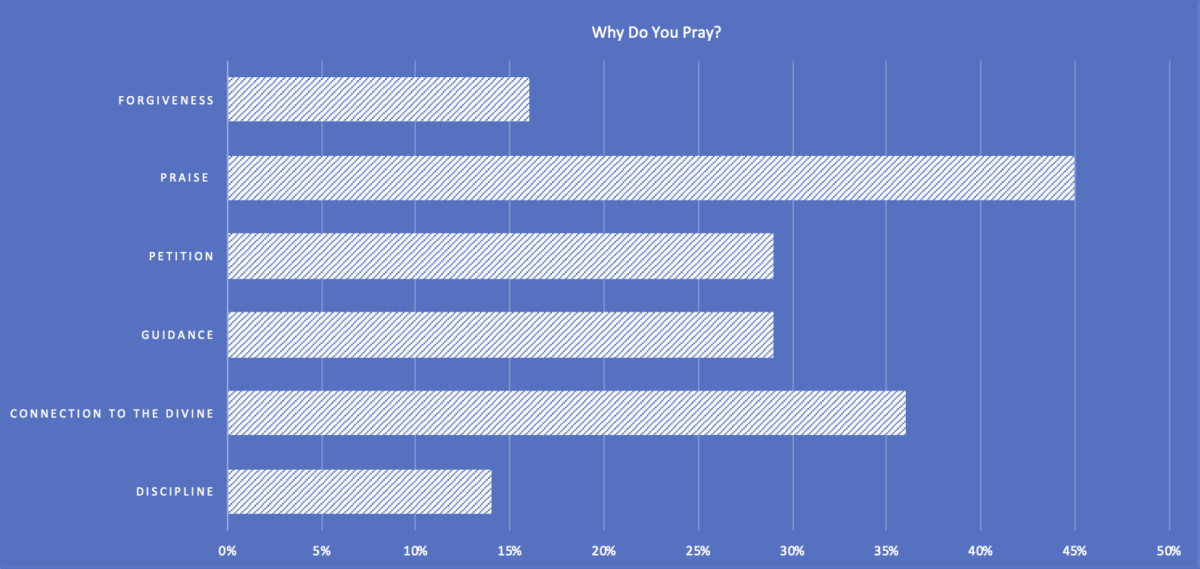

All but four of the respondents identified with at least one of the following six reasons for praying: discipline, connection to the Divine, guidance, petition, praise, or forgiveness. The majority of respondents (52%) noted that petitioning the Divine was a reason why they pray. Among the petitions were things such as health, strength, courage, and healing. A large plurality of respondents (45%) noted that praise and thanksgiving was a reason why they pray.

When asked to identify factors that kept them from praying, 77% of respondents noted lack of time and other distractions. 16% noted unfamiliarity with how to pray, and 9% noted having doubts about the efficacy of prayer. A surprising 29% of respondents noted no barriers to the frequency and intentionality of their prayer practice.

When asked to identify factors that kept them from praying, 77% of respondents noted lack of time and other distractions. 16% noted unfamiliarity with how to pray, and 9% noted having doubts about the efficacy of prayer. A surprising 29% of respondents noted no barriers to the frequency and intentionality of their prayer practice.

Instituting a new practice requires consistent repetition before it becomes a part of daily life. The same is true with daily liturgical prayer. Participants should understand what daily liturgical prayer is, why it is important, and how they can do it. I developed a two-part curriculum that further explains these three key elements, and offers a how-to guide for praying the Daily Office.

I also experimented with technological innovations that are making new modes of connection possible. A number of blogs and websites exist to aid the faithful in attending to their prayers. My community also experimented with offering Compline online on Sunday evenings. Parishioners received an email inviting them to a Zoom teleconference, accessible from a computer, tablet, or other web-enabled device, or by calling in on a telephone. Each night, attendees would log in on their phone or on their computers, pleasantries would be exchanged—just as they would be in the church prior to worship—and the service began at the appointed time. Links were provided to the readings, as well as to an online Book of Common Prayer for those who did not have access to a printed copy. This allowed participants to interact with one another in real time. It also allowed parishioners who were out of town to participate in a brief service of prayer with their community of faith.

My research confirms that one of the prevailing reasons that individuals desire a more robust prayer life is lack of time to devote to the practice. It is important to note that technology can be a helpful tool for connecting people in new ways. It can be particularly helpful in smaller and more rural communities, where in-person gatherings are not economically or geographically feasible. When it is used carefully and intentionally, technology can enhance relationships and practices. It stands to reason that the COVID-19 national emergency in early 2020 will cause further reliance on technology as a means of connection in communities of faith. My own community was better prepared for connecting in this manner during the pandemic because they were already somewhat familiar with online worship.

The final component of my project suggested several possibilities for revising the Book of Common Prayer that would make the Daily Office in particular and the prayer book in general more inclusive and more accessible. In brief:

- Offering a gender-expansive translation of the Psalter.

- Updating the current liturgical material to be more gender-expansive.

- Eliminating arcane language such as “versicle,” “invitatory,” “suffrages,” “venite,” “jubilate,” and “Phos hilaron” and offering the English translation of the Canticles rather than exclusively the Greek or Latin translations.

- Updating the rubrics and formatting of the Daily Office to give clearer direction about where Psalms, Canticles, Collects, lectionaries, and other liturgical materials can be found.

In light of the trends I have surveyed in this project, I believe that revision to the Daily Office should be considered carefully. Revision purely for the sake of revision is always a fraught proposition. The new is not always superior to the old, and there is no single prescription that will make the Daily Office a key fixture in the devotional practice of the faithful. Like all worship, the Daily Office possesses the power of conversion—the ability to transmit the unsearchable mysteries of God. Thus, the goals of liturgical revision in general and the revisions I have suggested in this section in particular are to facilitate an accessible means of devotion that is at once grounded in a particular time and context, and yet gives voice to the timeless tradition of daily liturgical prayer that spans two millennia.

The seismic shift taking place in Western Christianity invites new ways of thinking theologically about how the Church will respond to them and how these changes will affect the faithful. Put simply: How will the faithful remain faithful in the midst of a sea of changing norms, while also remaining open to discernment of how God is moving in and among us. Regardless of how one chooses to answer this question, the bedrock of what it means to be faithful to the God made known in Jesus Christ is found in prayer. Thus, an inextricable part of the answer to the question of how the faithful remain faithful can be put no more eloquently or plainly than in the 2,000-year-old admonition of the Blessed Apostle: Pray without ceasing!

[1] The Book of Common Prayer, 13, emphasis added.

+ The parish is fortunate to have a vocational deacon offering pastoral care and liturgical support, but this position is part-time and non-stipendiary.

[1] 1 Thessalonians 5:17, NRSV.

[2] “The 2017 Report of Episcopal Congregations and Missions According to Canons I.6, I.7, and I.17 (Otherwise Known as the Parochial Report)” (The General Convention of The Episcopal Church, 2017).

* “Regular” is defined as 30 or more occurrences in a given year.

[3] Iris DiLeonardo, “Congregations Offering the Daily Office in 2018,” Statistics (New York, NY: The General Convention of The Episcopal Church, October 1, 2019).

Marshall,

I am thankful for your leadership. Your research and the gleanings from it are helpful to those of us in denominations that are less steeped in tradition. Your focus on prayer and your desire to see the Daily Office become more widely used clearly comes from your own practice and the benefits of it. Prayer is indeed an important practice and the Daily Office can be a tool to a more faithful and abundant life with Christ. I pray blessings upon your ministry and am thankful for having gone through this program together.

Grace and peace,

Eric Sanford