A Study Across the Lines: An Exploration in Community

Reconciliation in Crumly’s Chapel

Serving as pastor in the outskirts of northwest Birmingham, Alabama has radically transformed my appreciation for Christian witness in community leadership. Social divisions and systems of othering continue to challenge the authentic witness of the church. I had the experience of witnessing the power of this divide firsthand when I as a young black man was appointed as pastor to the predom inantly white Crumly Chapel United Methodist Church (CCUMC). My very presence and appointment was a testament to the church’s growth—or to the bodacious leadership of some daring superintendents. A minority pastor had never been appointed to the church, and the church had a distinct reputation for being an exclusive white church in a community possessing a history of being unkind to people of color.

inantly white Crumly Chapel United Methodist Church (CCUMC). My very presence and appointment was a testament to the church’s growth—or to the bodacious leadership of some daring superintendents. A minority pastor had never been appointed to the church, and the church had a distinct reputation for being an exclusive white church in a community possessing a history of being unkind to people of color.

My experiences as pastor, studies in the D.Min Program at the Candler School of Theology and this study in community reconciliation led me to develop a model for bridging generational gaps and confronting racial tensions in the Crumly’s Chapel Community. The goal of this study was to implement model for cross-racially appointed pastors in the Crumly’s Chapel community to increase diversity sensitivity among youth and young adults and to encourage the development of more culturally sensitive youth and young adults. This study will help others better understand strategic methodologies for building inclusive churches in ethnically diverse communities. Through creating space to engage social justice related scriptures in multi-generational and interracial contexts, this model serves as a beta-test for a more inclusive church. To place this visionary model in context, I first examine the culture of othering at CCUMC. Then, I offer the project design with careful attention to the sample setting, methodology and module descriptions.

Assessing the Divide

CCUMC, like many other declining UMC churches located at the margins where urban and rural communities intersect, struggles to find viable strategies to increase worship attendance. Metrics used to measure church viability loom over the steeple of this struggling congregation as it faces the realities of closure if fails to increase worship attendance. Social stigmas and painful memories create barriers that stifle the church’s ability to build strong trusting relationships with its community. These relationships are further hindered when community leaders affirm divisions and support a culture where members treat the church like an exclusive country club as opposed the invitational body of Christ to welcome others. These models of exclusion limit the possibilities of community and lead to people functioning as consumers and not citizens. In the book, Community: The Structure of Belonging, Author and theologian Peter Block states that a citizen is “one who is willing to be accountable for and committed to the well-being of the whole. That whole can be a city block, a community, a nation, the earth.”[1] Citizens take ownership and actively participate in strategies that support the holistic development of all persons in community. Consumers on the other hand are only patrons of goods, constantly seeking to discover how assets in communities or organizations can serve them. Consumers take no responsibility for the future and as Block states, “They believe their needs can be best satisfied by the actions of others.” [i] When churches act like consumers, they give themselves permission to ignore the least, lost and left out persons living on the margins of community.

Race and Multi-Generational Trauma

Unfortunately, 155 years after the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation and fifty-five years after the Civil Rights Bill passed into law, the social cancer of racism continues to deteriorate the quality of life for many in the American context. Touching every aspect of community, racism impedes the development of trust. Racial tensions are high in and surrounding the Crumly’s Chapel Community.

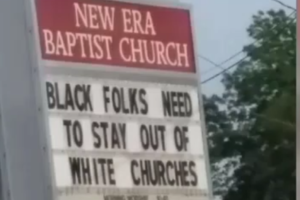

In Spring 2018, a very popular majority white congregation, released plans to launch a ministry campus in a majority black community near Crumly’s Chapel. Several black pastors in the area complained about the potential new church and the possibility of having more black people attending churches with white leaders. One pastor placed a message on his church marquee that read, “Black folks need to stay out of white churches.” The church plant was met with great resistance.

The community’s response revealed a habitus of resistance developed from a hermeneutic of suspicion often embodied by marginalized minority groups in the South. In The Post Black and Post White Church, Efrem Smith writes,

“The homogeneous church is not  without tension but there is a greater sense of cultural comfort then there is in the post black post white church. Sometimes leaders within the black church or more resistant to this kind of multi-ethnic and biblical discussion…Many argue that the black church is still needed – not because the white church is not welcoming to other churches, but because of a power dynamic that promotes assimilation.”[2]

without tension but there is a greater sense of cultural comfort then there is in the post black post white church. Sometimes leaders within the black church or more resistant to this kind of multi-ethnic and biblical discussion…Many argue that the black church is still needed – not because the white church is not welcoming to other churches, but because of a power dynamic that promotes assimilation.”[2]

Local pastors and community members’ responses further intensified preexisting racial tensions in the community. Unfortunately, the more deeply one embraces hermeneutics of suspicion the less likely they are to have compassion for persons of difference. This promotes the propagation of prejudice and preference and supports systems of othering. These systems and prejudices are compounded when embraced in social circles like families, churches and community groups.

Furthermore, CCUMC speaks of being prepared to open its doors to all people, but has not learned how to address the problems created by a troubled past. Several senior black community members carry painful childhood memories of riding their bikes and being run off the road by white people in Crumly’s Chapel. These elders also share heart-wrenching stories of having bricks and stones thrown at them if they left their predominantly black mining communities and walked anywhere near the more privileged Crumly’s Chapel. While these stories are shared by community members surrounding Crumly’s Chapel, they are still ignored by those who live inside. Despite this generational trauma, there has been little acknowledgement of the pain carried by disenfranchised community members. Without the church acknowledging the source of this pain, personhood fails to be affirmed and healing is thwarted.

Historical Tension

CCUMC was once the very center of this community. When the first four Caucasian families from Habersham, Georgia, established their small farming community in northwest Birmingham during the 1700s, they named the community Crumly’s Chapel. The families built a small wooden church to establish that structure as their central gathering space in the community. The church soon grew into a multi-functional facility for all community meetings and celebrations. This location also served as the community’s first schoolhouse.[3]

Shortly after the Civil War, Birmingham’s steel industry began to boom. The city saw exponential growth as mining companies attracted employees from all over the United States. Companies like the U.S. Steele Corporation and Drummond Company developed major mining camps in northwest Birmingham, and brought new families to the small rural farming communities. One of these mining camps, the Docena community, was placed just outside of Crumly’s Chapel. Their work radically impacted the lifestyles of those who called the area home. In the late 1800s, while performing an underground mining blast, a dynamite explosion ruptured the creek bed that furnished water to local farmers in Crumly’s Chapel. The effects of the blast on the water source created unexpected strain on the agricultural industry, forced community members to seek alternative means for economic stability, and led to increased resentment of the new neighbors.

Age and Othering

The average age of persons living in the community has steadily increased. This presents additional challenges for historic institutions seeking to connect with aging community members. Erik Erikson’s life cycle theory offers insight on how to understand the implications of aging on a community. Erikson asserts that as individuals age, they face a tension described as “integrity vs. despair.” In this stage, the individual becomes more settled in their identity and affiliations and concretizes their sense of identification with and participation in humanity. According to Erikson’s developmental theory, the older a person becomes the less likely they are to make significant overarching commitments to changing the way they socially posit themselves in relation to other persons, organizations or institutions in the community.[4]

Each of these social tensions undergird a culture of othering that shows up among majority and minority populations, fostering hate, instilling fear and propagating distrust. In the midst of this culture, CCUMC had to ask, “Who is our neighbor and how do we learn to love our neighbors?” The church has also been forced to realize that the aging population surrounding the church will be less likely to make new commitments with this congregation.

The Study Process

Study Participants

I extended an open invitation to local high school seniors and young adults (ages 17-25) living within three miles of CCUMC to join an open dialogue bible study that would discuss community tensions. Study Modules averaged approximately forty-three participants each week. Module participants consisted of eleven CCUMC senior adult members, two African –American middle-aged adults, one twelve-year-old female and approximately twenty-five to thirty youth and young adults. Of the youth and young adult participants, there was one African-American female each week, two Caucasian males (17 and 18) and the remaining participants were African-American males ranging in ages from seventeen to twenty-five. Senior adults were in the room during the modules, but they were not the subjects of analysis.

This process of hard community building conversation over meals was inspired by earlier research. In 2010, during my Masters of Theology degree, I devoted a year of study and experimentation on creating restorative initiatives for young minority males who were victims of sexual exploitation. Early in that study, I focused on ways that these victims of sexual abuse might be restored to community; however, after conducting several interviews, I realized that the work of restoration would not and could never be achieved solely by restoring these young men to the communities that surrounded them. Instead, they needed to be restored to the community and the community (or its stalwart pillars) needed to be restored to them. This revelation came as I listened to several stories detailing how police departments, schools, retail establishments, community centers and (of course) churches had become institutions of degradation for these young men. These places represented hope for many others, but for young marginalized minority males, those same institutions had come to represent hate, ignorance, fear, and damnation. This was particularly true of the church and its representatives.

Location

The Family Life Center was chosen as the location for the study because it provides recreational space and is strategically positioned in the center of the community. Although the Center is on the church’s property, it is located across the street from the main church and educational buildings, making it more welcoming to those who are less churched or have experienced pain from CCUMC. Additionally, this location lacks much of the traditional church architecture and images prevalent in other CCUMC buildings. Images depicting Jesus or celestial beings as white or black were intentionally removed throughout the interior of the Center.

Process

Crumly’s Chapel community youth enjoy cosmic basketball prior to their module study.

The program schedule included a time of recreational play that began at 5:30 pm. During this time, participants could enter the building, sign-in at the front desk and enjoy a host of activities. At 6:15 PM, all persons (from children to seniors) in the building were asked to assemble in the meal serving space for a community dinner. Before the meal was served, a youth or young adult was invited lead prayer and ask God’s blessing over the food and fellowship. When all meals were served, the intergenerational group sat down together for the discussion and meal.

The module discussions were designed around three research questions:

- Will Crumly’s Chapel youth and young adults participating in intergenerational dialogue about social problems that divide their communities increase their willingness to proactively address these issues?

- Can scriptural lessons affirming marginalized persons and supporting cross cultural initiatives inspire Crumly’s Chapel youth and young adults to express compassion for disenfranchised communities?

- Will youth and young adults in Crumly’s Chapel increase their willingness to identify strategies to help others after studying God’s story of divine redemption in scripture and hearing case studies of others who suffer in the world?

For six weeks the discussion and study followed a familiar pattern. After our communal meal, the study began with centering exercises where participants were invited to meditatively connect with themselves through breathing and sensory exploration. Next, participants began a process of thinking through their day, step-by-step, paying attention to the small but significant details. When this reflective portion was completed, the group listened to a case study of one person who either experienced hardship or celebrated a success that connected with the weekly theme. Study participants then read scripture highlighting hope for a marginal group or a cross-cultural encounter and discussed the three as a group. Each case study and scriptural component revealed deep human emotion and convictions, giving study participants opportunities to compare and contrast their personal experiences with those of others. While this practice was included to encourage empathy, I was more interested in hearing if participants would use their experiences to recommend strategies for serving others.

Six Modules

There were six modules that framed the study:

- Theme: Prejudice and Misperceptions

- Scripture: Jesus and Zacchaeus (Luke 19:1-10)

- Case Study: A reflection from a man experiencing homelessness on the streets of Birmingham, AL.

- Lesson Highlights:

- Stereotypes lead to misrepresentation of others in community and can make their lives difficult.

- Prejudice heavily influences our perceptions of others.

- Theme: Crossing Cultural Barriers

-

- Scripture: Jesus Outside Samaria (John 4)

- Case Study: A young girl reflects on being involuntarily displaced after war causes her hometown to become unsafe.

- Lesson Highlights:

- God meets us at in difficult places in life.

- Christians have a responsibility to cross barriers to reach others who may have experience trauma, misfortune or bad choices in their past.

- Good things can happen when we are cross barriers to engage new life.

-

- Theme: Finding Hope and Affirmation

- Scripture: The Story of Hannah (I Samuel 1)

- Case Study: A reflection from a from a Chinese-American daughter who celebrates her mother’s hard work to provide for their struggling family early in their immigration process.

- Lesson Highlights:

- Bullying can create short-term and long-term psychological effects.

- Bullying can take place on an individual or community level through systemic oppression and cultures of othering.

- Failure to acknowledge the reality or depth of others’ pains can be a form of bullying and can lead to psychological abuse.

- God acknowledges those in distress.

- Theme: Civil Responsibility

- Scripture: The Parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10)

- Case Study: Personal reflections of moments the leader and/or participants felt compassion from others.

- Lesson Highlights

- Ignoring others can be just as impactful as intentionally choosing to serve.

- Acknowledging others’ suffering and strategically assisting in the alleviation of that suffering is owning one’s place as a citizen in community.

- Theme: Character and Compassion

- Scripture: Parable of the Sheep and the Goats (Matthew 25:31-40)

- Case Study/Exercise: Envision an ideal community and reflectively identify the social stigmas and prejudices evident in your personal ideals.

- Lesson Highlights:

- All persons possess prejudices. We should learn our own and be willing to challenge or commit to changing them.

- Participants learn the definitions of social isms prevalent in the immediate community: ageism, classism, ableism, patriotism, sexism and ethnocentrism.

- Theme: Community-Building and Envisioning Change: Putting Theory to Practice

- Discussion: A critical thought exercise that asked participants to focus on others in the community and how they might mobilize their networks to bring people together

- Lesson Highlight: Participants were asked to 1) identify which social groups have the capacity to impact community challenges; 2) identify strategies each group could use; 3) identify in which of the named social groups they hold membership and 4) explain why they did or did not hold membership in the groups. All persons possess prejudices. We should learn our own and be willing to challenge or commit to changing them.

Major Themes Emerge

Rich discussion and sincere vulnerability revealed significant insight for churches seeking to cross social barriers in multi-ethnic communities like Crumly’s Chapel. Three major thematic findings stood out in the study: 1) Marginalized Crumly Chapel youth and young adults are more likely to participate with the church when they are invited as citizens, not consumers; 2) Authentic Christian witness requires intentional consideration of others; and 3) CCUMC must be willing to own its theology and participate in theophany.

Marginalized Crumly’s Chapel youth and young adults are more likely to participate with the church when they are invited as citizens, not consumers

Each participant came to the study with some level of history and experience with a church. Most of them had been invited to join congregations, but they had never been invited to take part in discussions pertaining to the development of the mission, external relationships, or the strategic direction of any church. Youth and young adult participants indicated that they took part in the study because they were asked to participate in an open dialogue. The invitation to participate in this dialogue was also extended by someone who had developed community rapport. In this process we learned that the church must extend invitations for others to be citizens of God’s kingdom who find places of belonging and connection within the church’s fellowship. This means that the church must choose “to be accountable for the whole (community), creating a context of hospitality and collective possibility, acting to bring the gifts of those on the margin to the center.”[5] It is not enough for the church to invite others to be consumers of its ministries. It must intentionally show genuine concern for others in community and create space for those others to partner with the church.

Authentic Christian witness requires intentional consideration of others.

The church must be willing to be a citizen within its community and reject practices that classify it as a consumer of the community or solely a vendor to its community. Transformation was revealed in the study when the Church became vulnerable and offered opportunity for others to speak and participate in its fellowship as partners, not patrons. I expected that youth and young adults would draw back and become silent as senior adults offered their perspectives during the study modules. This is how they had behaved in the past. To my surprise, the youth spoke up. They offered alternative perspectives to the adults’ perspectives. Youth and young adult participants admonished senior church members by explaining how senior members’ language was often offensive and/or would be misinterpreted when heard by youth at the local high school. On a few occasions, the young adults took special time to explain how the senior adults’ perspective clashed with themes of justice and inclusion that were revealed through scripture. They then took time to explain how Jesus’ example for all to be loved and respected might be encouraged in local community settings.

This was an important commitment for CCUMC. The language, contexts, understandings and misunderstandings revealed through module discussions were painful, but eventually empowering for CCUMC congregants. This act of vulnerability and possibly self-sacrifice for the sake of including others produced stronger relationships across generational and cultural barriers. In this. I saw the image of Christ on the cross.

The church must be willing to own its theology and participate in theophany.

When senior congregants and youth and young adult participants discussed scripture promoting cross-cultural dialogue for the sake of helping others gain access to power and privileges, the conversations quickly shifted into discussion of how churches have not been and can be more intentional about connecting with others. The goal of the church is to recognize God’s revelation without idolizing the mediums, the revelation itself, or its place in time. The church must be intentional about being alert and receptive to the many possibilities of God’s revealing—even if God gives revelation through marginalized youth and young adults. The church must show up in places unexpected and be an articulation of God’s presence in the world. It must not only seek to acknowledge historic theological revelation, but to consciously choose to see modern revelation, a promulgation of the aha moment exemplifying the character of God and the practice of God compassionately crossing barriers to connect with others.

Recommendations

The study served as a great introduction to building relationships and initiating critical dialogue across barriers in community. To continue this work, I recommend CCUMC and similar churches assess the context feasibility and implement the following strategies to strengthen their witness to others in community. Develop and implement missional objectives reflective of the church’s call to connect and minister in the local community. This can be done by churches developing cross-generational and cross-cultural leadership focus groups to discuss how the church understands its mission and can measure its effectiveness in achieving that mission. Secondly, the church should create space for faith-based discussion of scriptures focused on reaching/ministering to others outside of the dominant demographic represented in the local congregation. Hosting bible studies where texts affirming communication across barriers and the empowerment of marginal citizens reminds congregants of their responsibility to advocate for justice and mercy. Thirdly, the church should plan quarterly opportunities for non-member youth and young adults to dialogue about the nature of the church and community. These opportunities should include discussion of relevant current events, social relationships and the theological nature of the church. In this type of environment, listening and learning are critical.

Next Steps

My ministry assignment at CCUMC, this research project, and the entire D.Min. program have informed and reframed my ecclesiology and vision for the church. Chief among these revelations is my belief, “The church has to be the Church…for all people.” The need for the church to be the church for all people is complex and requires an ever-evolving process to assess and meet the needs of our continuously evolving communities. As technology expands our reach and exposes the diversity of those encountering our Christian witness, the church must be intentional about seeking to understand others in the world and diversifying its strategies to dialogue with them.

Next steps for this project include refining module discussion questions, seeking additional case studies to cover more of the diverse experiences people bring to community and running a similar beta-test for the larger congregation to determine if the larger CCUMC congregation produces the same indices of transformation reflected in youth and young adult participants.

[1] Peter Block, Community: the Structure of Belonging, (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 2008), 63.

[2] Efram Smith, The Post-Black and Post-White Church: Becoming the Beloved Community in a Multi-Ethnic World (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2012), 67-68.

[3] Ida Varnon, Transformation of a Wilderness (Birmingham: DeArman Printing Service, 1952), 13-14.

[4] Donald Capps, “Life Cycle and Pastoral Care,” in Dictionary of Pastoral Care and Counseling, ed. Rodney Hunter (Nashville: Abingdon Press, 2005), 248-249.

[5] Block, 63.

[i] Peter Block, Community: the Structure of Belonging, (San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc., 2008), 63.