For most of us, it’s work.

Our work schedules dictate when we wake and when we sleep. They define when we make plans for various appointments. When conflicts come up with work schedules, be it for personal or family reasons, we fret and stress over making adjustments to those work schedules as we accommodate family to our work.

This is, of course, not how we would choose to spend our time. We want our time defined by our highest priorities; for most of us, God and our familial relationships. And yet, this is often not how our lives go. In more lucid moments, we might be bold enough to think to ourselves:

There must be a better way.

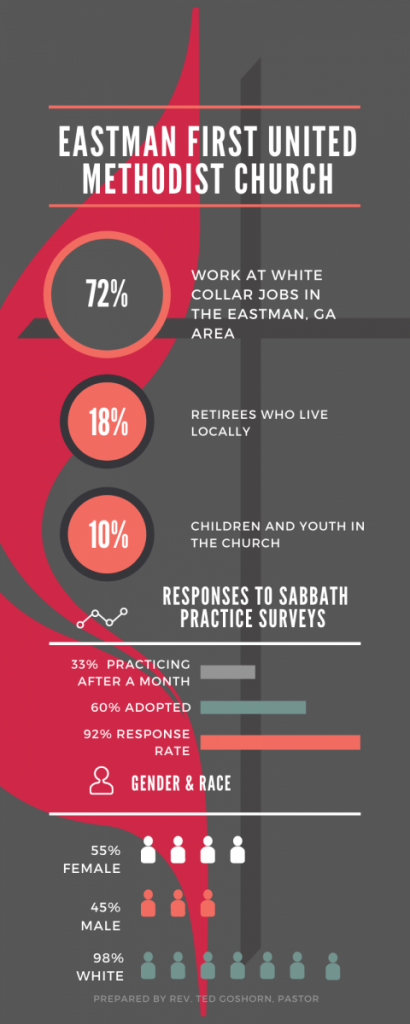

Families at Eastman First United Methodist Church (FUMC) in Eastman, Georgia, where I serve as pastor, approached me looking for that better way.

This congregation of mainly white collar workers in a small, rural, town in Central Georgia, recognized that priorities for God and family, for church and children, rarely defined their time. Work, instead, defined their time even though they felt that work was and should be a lower priority. They wondered in conversation with me how they could live their lives differently or, indeed, if they even could. I knew the answer is yes, based on my family’s experience, for:

God has provided a better way; a way called sabbath.

My family and I learned about that way from our pastor in 2012. As we faced significant challenges to our schedule and family time posed by my work, we decided to give sabbath practice a try. For us, that meant ceasing work from dinner on Friday until waking Sunday morning. Now in our ninth year, sabbath is a cherished family spiritual discipline; the center of our week. Our time revolves not around the demands of our work but, rather, sabbath forces us to make adjustments to our work schedules to accommodate sabbath itself.

In other words sabbath, rather than work, defines our time.

That includes defining time for our children. They call sabbath “Family Home Day,” a time they have come to cherish:

Video by Ted Goshorn, used with permission.

For our children, sabbath defines how they spend their time. While both enjoy school, they know that no matter how challenging Pre-K and fifth grade can be, they have that respite at the end of the week to renew and refresh, preparing them for the week ahead.

Our familial experience formed the basis for my Doctor of Ministry project on sabbath at Eastman FUMC. I wanted to share with families at the church the experience we had as a family discovering the power of sabbath to align time with stated priorities, just as church members had noted they wanted. The underlying assumption of my project was:

Sabbath can be taught as practice.

To teach sabbath as practice, I initiated a five-part sermon series aimed at teaching about and calling the church to keep six hours a week as set-aside time for rest, family time, and self-care. [1] During the sermon series, the pandemic interrupted church and life itself, forcing many families into the kind of quarantine common during the late spring of 2020.

While I was forced to pause the sermon series as we learned to do church in a post-COVID-19 reality, I realized that quarantine itself offered a great opportunity to simulate sabbath as practice; an opportunity for families to practice what I was preaching. Utilizing a series of lay leaders, surveys, and engagement via text and phone calls, I encouraged families to find that six hours a week in their schedule to practice sabbath, defined as taking time away from work and obligation to instead focus on family and doing things that brought them joy. After Easter, I reengaged in the sermon series, with the quarantine simulation now dovetailed into those sermons.

Surveys at the end of the project revealed that over a third of all church families, from those with young children to those retired and single and everyone in between, chose to adopt sabbath practice and all those families kept the practice after one month. One such family is the Eason family, consisting of Lacey, Ken, and their daughters ages four and almost two:

Video by Lacey Eason; used with permission.

Sabbath practice extends beyond work as defined by a paying job to any obligation that taxes. A retiree, active in the church and community, found sabbath to be just as freeing and helpful as families working full-time, paying, jobs. Martha Wright, aided by her grandchildren, speaks to her experience:

Video by Martha Wright; used with permission.

For several in the congregation, learning about sabbath as practice meant redefining their conception of sabbath. Prior to this Doctor of Ministry project, Leigh Law, a member of Eastman FUMC and our Children and Youth Director, thought of sabbath only as going to church on Sunday. As she heard the sermons, that conception changed, encouraging her to adopt sabbath practice and granting her a new view on how she spends her time:

Video by Leigh Law; used with permission.

Sabbath thus redefines work and, instead, comes to define time for the practitioner. Where before work may have set schedules and defined how and when they gave time to family and other priorities, sabbath comes to define time instead, placing limits on work and prioritizing family and faith.

Whether retired, young with children, or at any phase of life, sabbath provides freedom from the devouring nature of work.

Theologian Karl Barth put it just that way when speaking of sabbath. He notes that work, by its very nature, “tends to devour.”[2] The antidote for such is sabbath; and yet, Barth would argue that antidote is the wrong term. That’s because sabbath does not exist for the sake of work but, rather, for the sake of human life and flourishing.[3]

This is the reality noted by Hope College religion professor Angela Carpenter. For her, sabbath is the answer to the exploitative nature of the modern economy, where conveniences and an on-demand schedule create the illusion that “all time is available for work.”[4] When living under such an illusion, work defines how all time is spent and can even come to define the identity of the worker, resulting in self-worth becoming associated with productivity. This is the corrective offered by sabbath: not just release from the nature of work to devour time and identity, but to set humans free for “life and life abundant.” (John 10:10)

Rabbi Abraham Heschel, whose book “The Sabbath” is the gold standard on this subject, concurs that sabbath exists not as a corrective to work but for humans to enjoy life as God has designed.[5] He says that God created the sabbath on the seventh day of creation to provide a central day that would define time for humanity. All of life should be lived leading up to the sabbath (looking forward to it like Family Home Day for my children and the Eason family) and lived away from it (taking the joy and repose of the day into the demands of work, like Leigh Law and Martha Wright describe). Sabbath should be the hinge upon which our weeks turn; so central to our existence that it comes to define our time.

When sabbath is central to life, it has the effect of aligning our time with our priorities.

Yet, we don’t practice sabbath to achieve that. The alignment of priorities is rather the natural consequence of sabbath practice. While it may seem like semantics, the importance is real: when sabbath functions as a means to an end (alignment of priorities or respite from demands of work), sabbath becomes yet another thing to achieve, much like tasks at work or any other obligation. When sabbath is instead embraced as a gift, provided by our creator to define our time and how we spend our lives, we not only discover that our priorities align but we find joy and peace throughout our lives.

Sabbath, then, must define how we spend our time. It must be the centerpiece of our schedules; the hinge upon which our weeks turn. When practiced solely for the sake of having a scheduled respite from work, a disservice is done not only to sabbath itself but also to the practitioner who is unable to access the gift that sabbath is.

God has given sabbath as a gift to define how we spend our time, rather than as simply a respite.

For our nuclear family, for Martha Wright, Leigh Law, the Eason family, and indeed even for several of those at Eastman FUMC who did not adopt sabbath practice, sabbath as gift rather than respite or antidote for work was a revelation. Preaching that reality helped several families at the church discover sabbath and make it the defining and central part of their week, as evidenced in the videos above. Sabbath should be the hinge upon which our weeks turn. More than simply the antidote for the devouring nature of work, sabbath should define our time, granting us the gift of a flourishing life if we will choose to practice it on a weekly basis.

Which leaves only this question for you, the reader:

What defines how you spend your time?

Resources for further reading

Sermons on Sabbath by Rev. Ted Goshorn

Sermon 1: Make Our Lives Have Meaning | Scripture, February 26, 2020

Sermon 2: Work/Rest Rhythm | Scripture, March 1, 2020

Sermon 3: Building Godly Families | Scripture, March 8, 2020

Sermon 4: On-Demand Lifestyles | Scripture, April 19, 2020 (Note: the gap in dates indicates the interruption of the pandemic and initial quarantine, as indicated above)

Sermon 5: Whatever You Do, Do It In Love | Scripture, April 26, 2020

Suggested Reading List

For Church Classes

Marva J. Dawn’s book Keeping the Sabbath Wholly provides a robust and accessible overview of sabbath in its entirety. Unlike many other mass media publications, Dawn does not reduce sabbath to an antidote for the busy lifestyle but, rather, proclaims it as central to human existence, just as noted above.

Full citation: Dawn, Marva J. Keeping the Sabbath Wholly: Ceasing, Resting, Embracing, Feasting. Grand

Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1989.

Walter Brueggemann writes from the perspective of economic systems that entrap and snarl workers into valuing themselves and their lives based on what they can produce. While somewhat academic in language, the book provides thought-provoking discussion into the nature of work and how sabbath has provided release and freedom to live as God has designed.

Full citation: Brueggemann, Walter. Sabbath as Resistance. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press,

2014.

For Academic Research

Karl Barth provides a global perspective on the relationship between divine creation, as in Genesis 1, and the sabbath. He notes how God created the sabbath, providing not an end to the work but also a beginning. In doing so, he illuminates both traditional interpretations of sabbath via the creation narrative and reception history.

Full citation: Barth, Karl. Church Dogmatics, Vol. III: The Doctrine of Creation, Part One. Edinburgh: T. & T.

Clark, 1958.

The gold standard on the topic of sabbath from rabbi and scholar Abraham Heschel. While some examples are dated, his discussion of sabbath provides an in depth overview of sabbath, starting with its relationship to space and time and then moving through its implications for practice. Both philosophical and practical, Heschel gives tremendous insight into the nature of sabbath.

Full citation: Heschel, Abraham Joshua. The Sabbath: Its Meaning for Modern Man. New York: The Noonday

Press, 1951.

Patrick Miller expounds upon sabbath as understood through the fourth commandment as noted in Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5. Comparing and contrasting the two, he offers an understanding of the ethical implications of sabbath in particular.

Full citation:

Miller, Patrick D. The Ten Commandments. Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2009.

Notes

[2] Karl Barth, Church Dogmatics, Vol. III: The Doctrine of Creation, Part One (Edinburgh: T. & T. Clark, 1958), 214.

[3] Angela Carpenter, “Exploitative Labor, Victimized Families, and the Promise of the Sabbath,” Journal of the Society of Christian Ethics 38, no. 1 (2018): 84.

[4] Carpenter, “Exploitative Labor,” 82.

[5] Abraham Joshua Heschel, The Sabbath: Its Meaning for Modern Man (New York: The Noonday Press, 1951), 10.