A workshop leader asked the predictable question to a room full of ministers, “What is the purpose of the church?” One brave person honestly answered, “To survive.” This is the sad reality for many rural churches. These churches are living in the tyranny of the moment. All their energy goes into keeping the lights on or the minister paid. The Faith in Rural Communities project successfully assisted churches in thinking more strategically about their missional engagement work. These churches created a pathway to revitalize both their church and community. Churches are stronger when they see their ministry beyond the walls of their building and use their assets to positively impact the whole community.

Project Design

The goal of the Faith in Rural Communities project was to equip lay leadership with the vision and tools needed to build an innovative and strategic missional engagement strategy. The project worked with teams of six to ten lay leaders from eight rural, United Methodist churches. It began in the summer of 2018 and continued with a second cohort of churches in September 2019.

The Faith in Rural Communities participating churches worked with a coach through six sessions. The coach walked the church teams through three phases of discovery. First, the church discovered and celebrated their assets. This included the individual gifts of the church members and the overall church assets. The individual assets were broken into heart, head, and hands. Each church member was encouraged to answer the following questions:

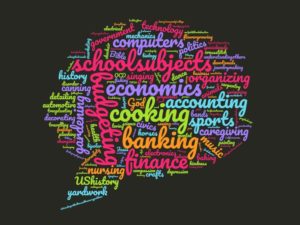

- HEART (Passions and Interests) – What do you love doing? What are some things you care a lot about?

- HEAD (Knowledge) What is something you know a lot about? What do you know so well that you could teach it? ( For example, how to change the oil in your car or how to grow tomatoes)

- HANDS (Skills) – What is something you can do with your hands? (For example, baking bread, playing the piano, fixing things around the house, taking care of older people)

The team also listed the church assets including their financial resources, physical assets, such as the church building, and their connections to community organizations or institutions.

Every church regardless of size or location had a long list of assets at the end of this step. This is important because it is common for small membership, rural churches to be distracted by what they are not. They compare their empty nursery to the days when the church was filled with children and youth. They compare their traditional worship service to the new church meeting in the local school with a full parking lot. This project focused on the belief that every church has assets to offer their community and the church’s missional engagement work needs to come from these strengths.

The second phase of discovery was for the church team to explore their community. Surprisingly, many people can live in the same area for decades or their entire life and still not know their community. The church team was asked to interview community leaders and people struggling in their community. They were given a list of possible people to interview including the local school counselor, a member of law enforcement, a local paramedic, and  several other people. They also focused on interviewing people whose voices are not always heard including people of color, young adults, immigrants, and other people commonly not invited into the conversation It was important for the churches to push themselves out of their comfort zone and talk to new people in this process. The team studied the demographic information for their county including poverty rates, health outcomes, economic development opportunities, and population trends. This exploration produced a long list of community challenges.

several other people. They also focused on interviewing people whose voices are not always heard including people of color, young adults, immigrants, and other people commonly not invited into the conversation It was important for the churches to push themselves out of their comfort zone and talk to new people in this process. The team studied the demographic information for their county including poverty rates, health outcomes, economic development opportunities, and population trends. This exploration produced a long list of community challenges.

The final phase was for the coach to help the team see where their church’s assets overlapped with their defined community needs. Churches looked for where they were being uniquely called to work with their community. The coach helped the team address the systemic causes of multiple community challenges instead of solely trying to respond to one need at a time. For example, one church worked with a community food pantry. The food pantry was successfully providing food to local families. This church team asked the deeper question of “why are people hungry in our community?” The answer led them to a partnership with the local community college to provide classes in their church fellowship hall. The church’s goal is to help people increase their skills so they can find a higher paying job and will no longer need food assistance.

Results

At the conclusion of the six coaching sessions, the churches developed a plan for their missional engagement work. Each church chose to focus on the area where their church’s assets connected with a community challenge. The plans included a summer camp focusing on healthy eating and fitness, a community meal that included English language classes, a middle school-aged suicide prevention program, and a summer reading program for early elementary-aged students.

Church leaders participating in Faith in Rural Communities project report their church realized a stronger sense of community within the church; a better understanding of the needs, assets and resources in the community; and greater awareness of their congregational gifts and how to use them strategically. These churches moved from the charity model of offering short-term fixes to community challenges to tackling the systemic causes of these challenges. This project showed that when a church is assisted in thinking more strategically and relational about their missional engagement they become places of community transformation and transform the relationships within the church.

A formal evaluation with the project participants discovered two factors played a significant role in the success of this project. The first factor was churches appreciated the coaching model of learning. The church leaders shared that many previous church training programs focused on successful models and encouraged the churches to follow prescribed steps. They said they left these trainings discouraged because they could not duplicate that model at home. By bringing the coach to the church and their community, it said the church was valued and worth investing in. It was also much easier to motivate lay leaders to participate if they did not have to travel to another town. It was important that the coach was able to adjust the pace of work to match the skill of each church team. The coaching model allowed the project to be relational and respond to the unique needs of each church team.

The second factor that contributed to its success was the focus on the church leaders and not just the minister. This took the pressure off the minister to always be creating the next new idea and allowed the church members to take ownership of the work. From the beginning of the process, we stressed that the minister was part of the team as a spiritual guide but the laity needed to be the ones doing the work. Even with the focus on the lay leaders, the minister was essential to the success of the project. Two of our eight churches had a pastoral change after the first year and their projects did not develop as well as the other churches.

This project continues now with a second cohort of twelve churches. The long-term planning for this cohort has been interrupted by COVID- 19 crisis. The church teams are applying the lessons learned about strategic, relational missional engagement to respond to immediate COVID-19 needs in their community. Many of these churches are responding creatively and having a tremendous influence on the community’s response to the pandemic.