A conversation with Dr. Kwame Phillips, co-author of “The People Who Keep on Going”: A Listening Party, Vol. I.

The Futures of Black Radicalism featuring an essay/mixtape by Kwame M. Phillips and Shana L. Redmond entitled “The People Who Keep on Going”: A Listening Party, Vol. I, is being promoted this Summer as a free e-book by publisher Verso Books. The mixtape playlist “is a people’s songbook, a soundtrack to the improvisational life and living of Blackness under the control of white supremacy. It is an effort to pull forward and give a name to what our bodies tell us with every needle drop, to hold tight that which combines individual voice and people’s rebellion . . .” (Redmond & Phillips, 2017:207).

Dr. Kwame Phillips is Assistant Professor in the Department of Communications at John Cabot University in Rome, Italy and an Emory Anthropology PhD (2014). Dr. Debra Vidali and Dr. Phillips have collaborated on several multimodal projects over the years, and she decided it was a good time to have a conversation with him about mixtape scholarship.

Debra Vidali: This is a phenomenally powerful project. Verso Books is promoting The Futures of Black Radicalism big time this summer, three years after the release. Congratulations! Can you say a few words about how the book speaks to the present moment?

Kwame Phillips: I think with the very visual global movement for Black liberation that is happening now, and the current push to share Black voices and authors, the book finds itself being particularly resonant. Black Lives Matter and other such organized movements are very much connected to the Black radical tradition, and anti-racist organizing is very much attuned to the historical and ongoing contexts of these struggles, which really is what the book speaks to.

DV: Your essay “The People Who Keep on Going”: A Listening Party, Vol. I, co-authored with Dr. Shana L. Redmond is deeply multi-layered and multimodal. The argument exists both in the book and on the mixtape. Inviting the listener to undergo an experience is foremost for the project. What do you hope people get/experience/do with this work? And why did you decide to call it a party?

the invitation is to first, recognize the role that Black music has played in social justice movements . . . [and] second, experience the specific curation of music chosen to articulate the Black radical tradition

KP: Well it’s specifically a listening party, which implies an invitation to gather and share in a curated experience. The chapter is the articulation and curation of that experience. And the invitation is to first, recognize the role that Black music has played in social justice movements, something Redmond articulates in her book Anthem when she says “These sonic productions were not ancillary, background noise – they were absolutely central to the unfolding politics because they held within them the doctrines and beliefs of the people.” And the invitation is to second, experience the specific curation of music chosen to articulate the Black radical tradition. So what we hope people get from the listening party, through the text and the mix, is, citing Robin D. G. Kelley in his book Freedom Dreams as we do in our chapter, an understanding of how music creates “a world of pleasure, not just to escape the everyday brutalities of capitalism, patriarchy, and white supremacy, but to build community, establish fellowship, play and laugh, and plant seeds for a different way of living, a different way of hearing.”

DV: Yes, “a different way of living . . and hearing.” So, together you create an elegant and hard-hitting flow of historical analysis, cultural critique, musicological-aesthetic evaluation, and celebration. Alluding to early 20th century phonographic reproduction, you call it “a hypothesis in wax” (207). Could you talk about the origins of the project, and your collaboration with Dr. Redmond?

This time the collaboration was more involved since the mixtape and the chapter exist symbiotically. I’d argue that the mixtape and the chapter are a single multimodal entity.

KP: Dr. Redmond approached me to collaborate. She has done extensive and highly praised scholarship on music, race and politics. She had the idea in mind to do something multi-modal with the chapter, and it is something we had done before for her book Anthem which explores how the genre of anthemic music, emblematic of Black solidarity and citizenship, contributed to the growth and mobilization of the modern, Black citizen. For that collaboration, she asked me to make a mixtape accompaniment to the book. This time the collaboration was more involved since the mixtape and the chapter exist symbiotically. I’d argue that the mixtape and the chapter are a single multimodal entity.

DV: Nice. What about the disciplinary and technical expertises that each of you brought into the collaboration? What was the research process and what was the production process? And where, for you, does being an anthropologist fit in?

KP: We both explore music, race and politics; her methodology is maybe more analytical and mine more artistic, but we’re both capable and versed in each other’s processes. The research process starts with brainstorming possible songs. It’s really an exhaustive search for what we think will be the right and appropriate playlist. She trusts me to do that work and then we are in constant contact about it. It involves a lot of reading, archive searches, conversations with friends and colleagues, whatever it takes really. I usually end up with as many as 200 songs, that I then narrow down to a rough playlist of 15-20. I listen to talks, interviews, other sound sources that might be relevant to mix in, and then it’s the long process of mixing and creating an articulated perspective through sound.

The anthropology of it, is that it’s an articulation of culture and human experience, as it relates to the Black radical tradition and the role of Black music, through extensive research of extended music archives, presented in a non-traditional form.

DV: There’s a lot of buzz about experimental ethnography, multimodality and creating an “anthropology otherwise.” I’m thinking of Chin’s work, and work by Dattatreyan and Marrero‐Guillamón (2019), McTighe and Rashig (2019), and so many others. Do you see your work in that conversation? Or are there other conversations you are engaging?

One of my commitments in academia, as a scholar, has been to utilize archives and voices and epistemologies and methodologies that may not often get regarded in academia as being valid. In my work, I quote rappers alongside theorists because I genuinely believe Black Thought of The Roots and Bourdieu are equally valid.

KP: One of my commitments in academia, as a scholar, has been to utilize archives and voices and epistemologies and methodologies that may not often get regarded in academia as being valid. In my work, I quote rappers alongside theorists because I genuinely believe Black Thought of The Roots and Bourdieu are equally valid. I interrupt text with image in my work. I’m trained as an ethnographic filmmaker, and I’ve moved more into broader sensory media work as of late, specifically working with sound, so multi-modality has always been what I do, has always been the method I thought most appropriate for my work. I’m accustomed to answering whether my work is experimental or artistic, and I challenge any notion that makes what I do sound alternate. I don’t think of what I do as being an alternate form, or the use of art and the aesthetic as being an alternate form, it’s just one that hasn’t historically been thought of as traditional. That’s something that Anna Grimshaw taught me, “It is not a question of exchanging “anthropology” for “art” or of pursuing “formalism” for its own sake, [but] increasing recognition that it is possible to work more expansively with the notion of the aesthetic itself” (Grimshaw, 2011).

As it relates to the concept of “anthropology otherwise,” I’m not sure how much of what I do currently is about producing new worlds or new ways of being. I think what I do is reveal existent worlds and existent ways of being. To the extent that the works challenge and resist similarly existent oppressive worlds and speculate about free spaces, maybe that is the ‘otherwise’ of it. But this is truly a tension I fight with a lot. I’m not sure I see my work as hopefully speculative, as much as I tend to feel it as angrily present and cathartic.

DV: That’s powerful. So to bring up another anthropology question: Is your work a way of “doing ethnography” in/with/through music?

But the music is never untouched. I am manipulating it, I am mixing it, I am remixing it, reordering it, sequencing it, adding to it, putting it in conversation with other sounds, creating an entire soundscape, and using an aesthetic of the mixtape that is connected to a history of subversion and ‘do-it-yourselfness’ that operates outside and on the margins of dominant power structures.

KP: I see it as more doing ethnography though sound, and music is one of those sound sources. But the music is never untouched. I am manipulating it, I am mixing it, I am remixing it, reordering it, sequencing it, adding to it, putting it in conversation with other sounds, creating an entire soundscape, and using an aesthetic of the mixtape that is connected to a history of subversion and ‘do-it-yourselfness’ that operates outside and on the margins of dominant power structures. So, as R. Murray Schafer would say, soundscapes have the power to create the sensation of experiencing a particular acoustic environment. I’m trying to convey sonic narratives of the disenfranchised, the under-represented, and the marginalized in a manner not bounded by academic tradition or traditional form.

DV: I’m really interested in hearing you talk more about the different ways that people are producing scholarship in sound. For example, there’s our co-authored Kabusha Radio Remix project which engages issues of media politics, elder authority, and public intimacy in Zambian radio advising, as well as the haunted nature of archives. It exists as a physical installation, a mixtape, an audio publication about sonic collisions, web-hosted material, and more. Your mixtape works with a music playlist which has a historical, thematic, and aesthetic logic. This logic is amplified with both the music sampling and the interspersing of other audio elements such as recordings of scholarly analysis and public speeches. How do you think about these different sonic possibilities for developing theories and arguments? And where can we go further with this?

I’d love to live mix a conference talk. I’d love to give a conference talk all in rhyme. I’d love to write a whole academic text in rhyme.

KP: I think, at least I hope, there are infinite sonic possibilities. I once saw Cathy Lane give a keynote presentation, and it was a seamless mixture of her speaking, her remixing her voice, her adding sounds. It was amazing and inspiring. I deleted all my conference PowerPoints after that. There are certainly ways to present theory that foreground sound. And I’ve started to experiment with conference presentations in this regard. I presented at one conference and didn’t speak at all, and instead played a 20 minute what I called a visual mixtape that explored repetition and the meditative impact of mantras. I’d love to live mix a conference talk. I’d love to give a conference talk all in rhyme. I’d love to write a whole academic text in rhyme. In terms of developing theories and arguments, knowledge production through sound is obviously a choice we can make if we learn to appreciate how sound informs our meaning making. I teach a sound design course, and each year students are asked to create a collaborative sound map of our campus neighborhood, but do so without depending on a visual component to guide the listener. So it really forces them to understand the spaces they inhabit from a sonic perspective.

DV: Yes! Sign me up for the next Remix Conference, or DJ’d conference paper session! Any new listening parties in the works?

KP: I’m currently fine tuning the visual mixtape called “The Imagined Things” that explores repetition and the meditative impact of mantras in Solange Knowles’ music. I’m writing a chapter on that for an edited collection called Diva coming out on Bloomsbury Academic. I most recently published The Social Distancing Mixtape, which is more of a playful work about the Covid-19 experience.

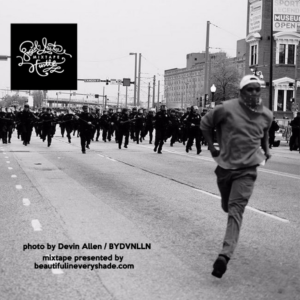

But in terms of work that is closer to “The People Who Keep on Going,” there is Pleasure/Liberation, which is a collaboration with Dr. Mark Anthony Neal and Redmond that explores themes of pleasure and liberation in Black political music. There is the Social Justice Hustle Mixtape, a collaboration with Carlton Mackey, founder of the grassroots movement “Beautiful in Every Shade” and multidisciplinary artist Christy Namee Eriksen, created as part of a campaign to inspire a global movement for social justice. There’s the Anthem mixtape, and there’s “50 Shades of Black Music: The Mixtape,” another collaboration with Carlton Mackey, and graphic artist C. Flux Sing, which is more of a comprehensive curation of the history and diversity of Black music traditions. All of these are hosted on my Dreadstar Movement Soundcloud site. Dreadstar is a moniker I used in college when I used to DJ. I retained it because it forces me to merge worlds between art and academia, anthropology and activism. I want everything to share space, hence I now make scholarly mixtapes.

DV: Thank you for this great exchange! And for your work. What track should we use to close out?

KP: Arg. The hardest question yet. In keeping with the aspirational nature of anthropology otherwise, I’d say Donny Hathaway’s version of “Someday We’ll All Be Free.” The most beautiful voice. The most beautiful dream.