In my experience, the vast majority of philosophy courses use one, and exactly one, assessment technique: papers (and occasionally a participation grade). At times an instructor will require a summary of the reading (to demonstrate comprehension), and at other times, a critical response (to demonstrate both critical and creative thinking). Though the prompts vary, however, the format remains the same. While I am generally pretty good about having them write drafts and then improve upon those, I still have trouble getting students to craft a sound and reasonable argument. This class is providing me an opportunity to examine the grading rut I have fallen into, but unfortunately I’m having trouble seeing a better way to assess student learning and critical thinking than having them write papers.

My goals for my students, when they complete an assessment, are as follows:

-that they demonstrate that they understand the texts we’ve read,

-that they can think about the text as an argument,

-that they spend time carefully considering the argument as a whole,

-that they think critically about the argument,

-and that they formulate their own thoughtful response to it.

Source: Vanderbilt’s Center for Teaching

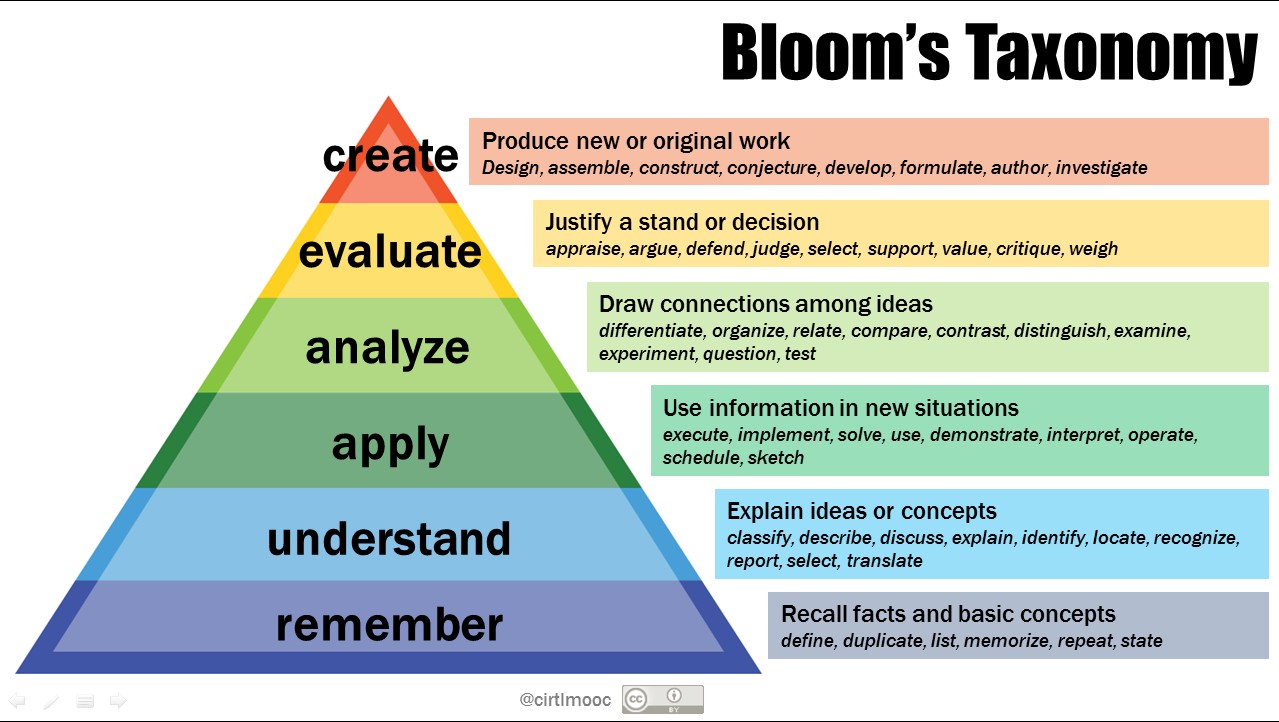

Essentially, my goal is for them to work their way through Bloom’s taxonomy, and in writing a paper, to show me how they did it and where they ended up. I do sincerely believe that writing a paper is one of the best ways to do that, because it forces them to slow down and think.

However, I can think of two things that might improve their learning outcomes.

- Taking them through the stages of Bloom’s taxonomy paper by paper. In other words, require that the first paper be a summary, the second paper be an application, the third paper be analysis, the fourth paper be a critique, and the fifth paper be an original response. In this way, I can lead them through the process step by step, rather than just throwing them in the deep end.

- Using Voice Thread to break the argument into pieces for them, presenting them with a one part of it per frame, and then allowing them to respond to individual sections of it (bonus: getting to incorporate images for the visual learners). I think this might prevent them from getting overwhelmed by the task of taking on the argument as a whole, and instead break it into comprehensible, manageable chunks. It would also keep them from misunderstanding the text and then trying to base their whole response on a misunderstanding (which is a particularly frustrating paper to grade).

Both of these hinge upon breaking both the material and the students’ responses to it into smaller pieces. I think it’s a reasonable goal and one that would greatly benefit my students.

I find the Voice Thread idea intriguing. You would break down a philosophical argument into different ideas/parts, to allow students to better understand it? And then they would be allowed to also respond to your Voice Thread posts incrementally? Can you clarify/elaborate?

Yes, since every argument is composed of premises and a conclusion (and possibly a few sub-conclusions), I was thinking I’d break down the argument and put each piece on its own slide. To use Mill’s argument for utilitarianism as an example, the slides might be divided up like this*:

Premise 1: The only proof that a thing is desirable is that people actually desire it.

Premise 2: Each person desires happiness for herself.

Subconclusion 1: Each person’s happiness is desirable for herself.

Premise 3: What is desirable is a good.

Subconclusion 2: Each person’s happiness is a good to that person.

Conclusion: General happiness is a good to the aggregate of all persons.

Principle of Utility: The best action is that which produces the greatest happiness for the greatest number.

If students were able to see and discuss the argument laid out like this, they might have an easier time formulating objections. Premise 3, for example, is low-hanging fruit when it’s laid out explicitly—most students are able to point out that we desire lots and lots of things that we probably wouldn’t call “good” for us. So in my hypothetical class, they’d start a discussion on that Voice Thread slide discussing whether or not all desirable things are good, what exactly “good” means here, etc.

*The actual logical structure of Mill’s argument is the subject of much debate, but this is a reasonable approximation.

Ah, okay, makes a lot of sense. The same structure might be valuable in other fields as well, for example when we think about teaching ENG 101. Breaking down the elements of a strong paper could be a good idea, even though formulaic lessons are not always ideal. I guess Voice Thread would give students and instructor the chance to qualify particular ideas.