The history and contention surrounding the commercial sex trade is reflected in its most basic form: its terminology and definitions. These definitions, terminology, and their direct relation to where perceived power reveal just how difficult it is to talk about the issue without confronting the legacy of the feminist sex wars of the 1970s and 1980s.

The feminist movements of the 1970s and 1980s were marked by passionate debates surrounding sexuality, pornography, and the sex industry, collectively known as the “Feminist Sex Wars.” These ideological clashes among feminists significantly influenced contemporary discussions on prostitution and commercial sex work.

In navigating this legacy, the feminist sex wars are often reduced to a black-and-white debate between “exploitation” versus “empowerment,” (Comella, 459) conceived of as a straightforward conflict between antipornography feminists on one side and pro-sex feminists on another, respectively.

(Photo credit: Kim Samuel)

This polarization, tied directly to media narratives surrounding sexuality (Bracewell, 24), often portrays sex workers as either “helpless victims or empowered escorts with unfettered agency” (Comella, 459). Through this framing, the complexities of sex workers’ lives and experiences are ultimately reduced to something eye-catching, inflammatory, and palatable. So let us explore what are these ideas that still influence policy:

1. Autonomy and Choice:

The most notable spark of contention within the Feminist Sex Wars is the terminology between “sex work” and prostitution.”Anti-pornography feminism argued that pornography and certain sexual practices, including sex work, were forms of violence against women. They believed that these activities perpetuated harmful stereotypes, objectified women, and reinforced patriarchal power structures (Catharine MacKinnon and National Organization for Women). Sex-positivist feminists, on the other hand, including activists like Gayle Rubin, sought to challenge this more conservative and moralistic attitude within feminism. They emphasized sexual agency, autonomy, and the right of individuals to make choices about their own bodies and sexual practices without moralistic judgments, viewing prostitution as sex work and inherently an “occupation” (Rubin, 150). The discourse between these two branches of feminism, antipornography and pro-sex, established many of the core arguments used in contemporary sex trade discourse, and their respective terminology directly relates to where on views power, consent, and agency within the commercial sex trade.

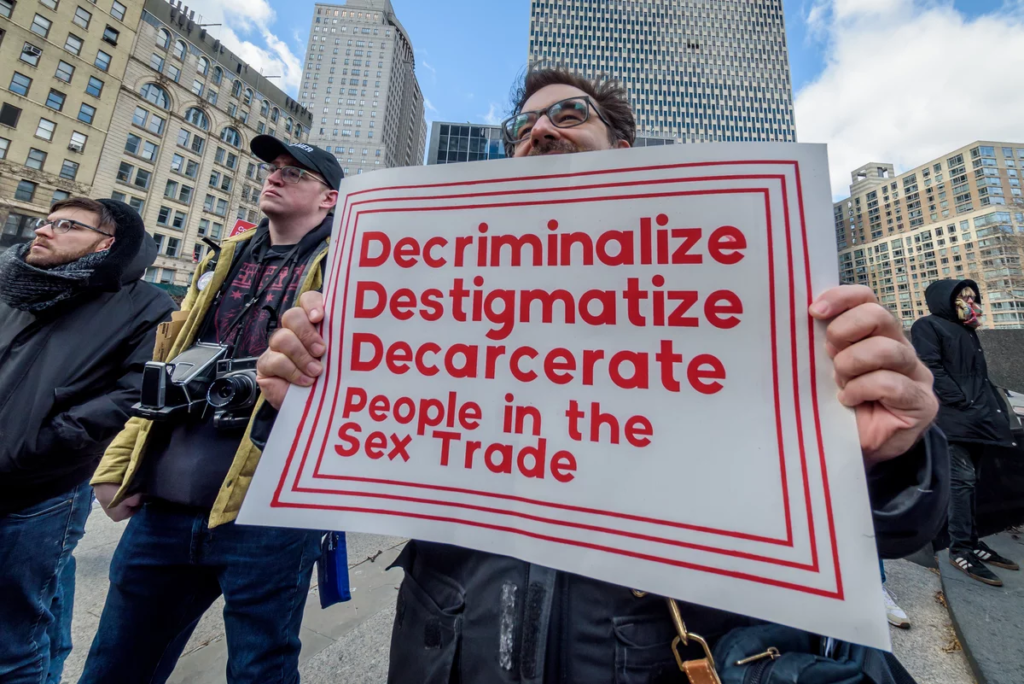

2. Legal Frameworks and Decriminalization:

The sex-positive feminist stance has contributed to the push for decriminalizing sex work in various parts of the world. Activists argue that decriminalization would enhance the safety and well-being of sex workers by allowing them access to legal protections and basic labor rights. Conversely, anti-prostitution feminists often contend that decriminalization could perpetuate gender-based violence and exploitation. Anti-pornography feminists Andrea Dworkin and Catherine MacKinnon, in contradiction to decriminalization, argued that the law could be used in the protection of women to work against gender-based violence.

3. Sexuality and Empowerment:

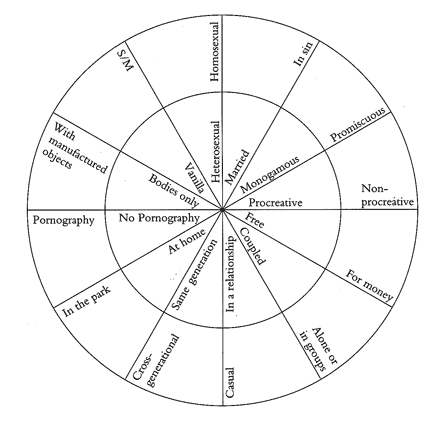

The sex-positive feminist perspective has influenced contemporary discussions by emphasizing the importance of recognizing and respecting diverse forms of sexual expression and labor. This viewpoint challenged the traditional narrative that frames all sex work as inherently degrading and disempowering, promoting the idea that some individuals may find empowerment and economic independence through their work in the sex industry. A key example of this is the charmed circle by Gayle Rubin, that critiques dominant sexual norms and the hierarchy of sexual deviance versus sexual acceptance.

Let us continue with Gayle Rubin’s Charmed Circle…

The charmed circle depicts the hierarchy of dominant, acceptable sexual norm. Heterosexuality, monogamy, and “free” (Rubin, 157) are deemed not only acceptable but the only acceptable sexualities according to dominant sexual norms. Other sexualities that can be perceived as deviant to this, like homosexuality, BDSM, and sex for money (prostitution) are marginalized, stigmatized, and placed on the outskirts of our society, as shown by their placement at the outer layers of the circle. (Photo credit: Rubin, 157).

Rubin’s arguments against the moralistic condemnation of non-normative sexual practices, including sex work, advocate for a more inclusive and tolerant approach that moves beyond previous conservative feminist ideas that sex workers are helpless and without agency.

This outlook was and continues to be questioned: If a woman begins working in prostitution before they are an adult, participate in it due to fear of violence from their pimp or partner (Giobbe 33), or are participating in the trade due to dire financial circumstances (including prostitution being the sole option for financial independence) (Monto, 162), is it a choice?

The Feminist Sex Wars was, in many ways, the beginning of the critical feminist and legal interrogation into where consent and power lies in the commercial sex trade. The Feminist Sex Wars of the 70s and 80s played a pivotal role in shaping the contemporary discourse on prostitution and commercial sex work. The clashes between anti-pornography feminists and sex-positive feminists have left a lasting imprint on the feminist movement, contributing to a more nuanced and complex understanding of the issues surrounding sexuality, agency, and empowerment within the context of the sex industry.

References

Bracewell, Lorna Norman. “Beyond Barnard: Liberalism, Antipornography Feminism, and the Sex Wars.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 42, no. 1 (2016): 23–48.

Carmon, Irin. “Who Actually Lost the Sex Wars?” The Cut, August 12, 2022. https://www.thecut.com/2022/08/the-sex-wars-sexual-culture-today.html.

Comella, Lynn. “Revisiting the Feminist Sex Wars.” Feminist Studies 41, no. 2 (2015): 437–62.

Garsd, Jasmine. “Should Sex Work Be Decriminalized? Some Activists Say It’s Time.” NPR, March 22, 2019, sec. Business. https://www.npr.org/2019/03/22/705354179/should-sex-work-be-decriminalized-some-activists-say-its-time.

Giobbe, Evelina. “An Analysis of Individual, Institutional, and Cultural Pimping.” Mich. J. Gender & L. 1 (1993): 33.

Lancaster, Roger N. Sex Panic and the Punitive State. Univ of California Press, 2011.

MacKinnon, Catharine, and National Organization for Women (NOW). “MacKinnon Q & A NOW’s Views on Decriminalization.” National Organization for Women, 2019. https://now.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Comms-Team-QA-1.pdf.

Monto, Martin. “Female Prostitution, Customers, and Violence.” Violence Against Women 10, no. 2 (2004): 160–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801203260948.

Rubin, Gayle S. “Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality.” In Culture, Society and Sexuality, 143–78. Routledge, 2002.

Samuel, Kim. “The Stigmatization Behind Sex Work.” Samuel Centre For Social Connectedness, May 4, 2018. https://www.socialconnectedness.org/the-stigmatization-behind-sex-work/.

Weeks, Jeffrey. Sexuality and Its Discontents: Meanings, Myths, and Modern Sexualities. Routledge, 2002.

“Why Sex Work Is Real Work | Teen Vogue.” Accessed December 10, 2023. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/why-sex-work-is-real-work.