“Twelve lines of dialogue,” “two and a half hours of runtime,” “world’s saddest flirting,” and “Academy Award-winning glance choreography.” These are some of the similarities SNL found between Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019) and Ammonite (2020) in their fictional trailer called “Lesbian Period Drama.” In this skit, SNL highlighted the apparent trend in queer filmmaking that restricts lesbian narratives to the 18th century.

Though SNL was just trying to be funny, “glance choreography” is an aspect of the critical concept that I call the queer lens.

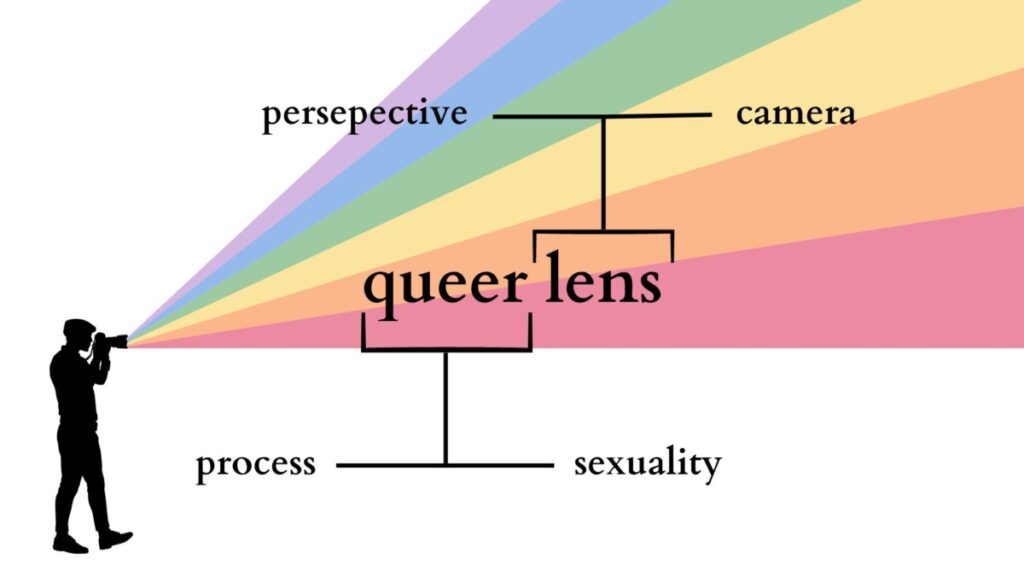

There are numerous theorists who specialize in the study of the “glance” in cinema, or more specifically the gaze, notably Laura Mulvey, Jacques Lacan, and bell hooks. Filmic gazes, however, emphasize spectatorship and the inherent power dynamics within. Rather than focusing on spectatorship theoretically, I think it more fitting to consider the role of the camera that singles out the hidden details that fuel queer tension and desire, the details found most often in the form of these looks and gazes. That’s why I call it the queer lens; the duality of the “lens” serving as one of the camera’s and as one of a perspective (Fig. 1).

In this blog, I will take you through a little journey of how the queer lens works in the filmmaking world with Céline Sciamma’s 2019 Cannes Best Screenplay-winning film, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, as our case study.

To start off with a brief summary, Portrait is set on an island in Brittany, France, in 1770. The film is about a painter, Marianne (Noémie Merlant), who is commissioned to paint a wedding portrait of Héloïse (Adèle Haenel), a reluctant bride-to-be who has just left the convent. Due to Héloïse’s resistance for the marriage and subsequent refusal to sit for a portrait, Marianne must do so without her knowing. She observes her carefully by day, acting as a companion on Héloïse’s walks so she does not follow the same fate as her deceased sister, and painting her secretly.

The women in Portrait engage in an equal, reciprocal relationship, favoring feminine ways of looking that is often negated in hegemonic, patriarchal narratives and ways of looking. The queer lens allows such looking amidst oppressive environments through the use intentional cinematography. Let’s take a look at how Sciamma and her director of photography, Claire Mathon, made this work.

Marianne’s POV Shots

Throughout the beginning of the film, Marianne and Héloïse’s walks consist of close shots of Heloise’s face from behind, so as to show Marianne’s point of view trailing behind her. The fact that Marianne cannot get ahead of Heloise subtly hints at the difficulty Marianne encounters with memorizing Héloïse’s face to paint later at night by candlelight or in the morning. But perhaps more importantly, the fact that Héloïse is always ahead opens the possible interpretations for the several seemingly furtive glances towards Marianne – is Héloïse curious? Scared? Suspicious? Maybe even interested? The fluidity of such an aesthetic mirrors the fluidity of queerness itself, both in its ever-changing meaning in academia and its fluctuation of sexuality (Fig. 2).

A Look is Worth a Thousand Words

Even when the two sit next to each other – a tight medium close-up shot’s distance apart – Marianne can’t just turn and stare at Héloïse discreetly without drawing suspicion to her real mission (Fig. 3). In some ways, however, the consistency of such glances and gazes contribute to the underlying, budding connection and desire between the two women. The tightness of the shot forces Marianne and Héloïse’s proximity much closer together than one might expect between two women who had just met, especially in the 18th century. Every time this occurs, they hardly break eye contact and look each other up and down carefully; Marianne perhaps because it’s her job and Héloïse perhaps due to her continued curiosity or interest.

It is the queer lens that offers this perspective in a world where the women can transport out of the restrictive reality and destinies they are bound to. The camera’s lens is queered in the looks rather than the dialogue, as “what remains unsaid remains most poignant” and most illuminative. SNL’s joke about the “twelve lines of dialogue” in the “two and a half hours of runtime,” though exaggerated, hints at exactly these looks that do all the talking to promote the growing attraction between the women. Consider this: queer during this time period meant “strange or eccentric,” so it’s not like Héloïse really had the option to ask Marianne, “Wait, are you queer?” It’s the camera’s role in the queer lens to consider this question in-explicitly.

Transformative Shot-Counter Shots

After Marianne reveals her true purpose to Héloïse, showing her the first rendition of the portrait, Héloïse resents Marianne’s failure to really see her and capture her vitality (“Is that me? Is that how you see me?”). I interpret this narrative development to suggest that Héloïse had sensed an attraction growing between them – as made evident from the looks leading up to this moment – but now wishes to be seen for who she really is, more so by Marianne than by the Milanese gentlemen whom she is predestined to marry. This inspires a collaboration between the women, as this time Héloïse agrees to sit for Marianne’s painting.

Mathon uses conventional shot-counter shot composition with a focus on medium close-up shot variations to govern the love relations fueled by looking in these moments that the women collaborate for the painting. She does so in a new, transformative way that bridges the gap between the painter and the muse. It becomes evident that the sexual attraction that the queer lens builds is not built on domination or ownership; rather, it is “grounded in mutuality and understanding.”

Additionally, it’s important to acknowledge the considerable amount of time, energy, and most importantly, looking required for drawing, sketching, and painting (Fig. 4). So it’s one thing that Marianne sketches Héloïse sleeping later at night, but it’s another thing when Héloïse wakes up to notice her, and they inevitably share a gaze and a smile. To capture someone’s presence and vitality on a piece of art is to not just see them, but to understand them – something Marianne achieves better than perhaps the future male recipient of the portrait ever will.

Queering the Period Drama Setting

The 18th century setting wherein Portrait takes place inherently incorporates motifs often associated with romance, such as low lighting coming from natural sources like candles and a fireplace that warm up the atmosphere when Marianne sketches Héloïse. As Mathon said in IndieWire’s Filmmaker Tookit podcast, “[Céline Sciamma and I] were talking about re-inventing and enhancing our 18th century image to current realities.” I interpret this as the film not just showing a painter painting, but it becomes a painting (Fig. 5). There is an abundance of softness, both in terms of the lack of hard shadows and the texture of the actors’ skin suggesting that of an oil painting. “We often discussed the faces in terms of the landscapes,” Mathon mentioned, elaborating on the detailed and heightened color choices.

Sciamma and Mathon’s meaningful choices in the mise-en-scène – a term for everything in front of the camera, from costumes and make-up to lighting and blocking – transports us to this reinvented, queered 18th century reality where the once illegal and unacceptable desires are allowed to exist. Echoing the nature of the queer looks necessary for painting the portraits, the painting-like nature of the environment queers the 18th century setting. This offers Marianne and Héloïse a space for agency to navigate their lives that they perhaps would not have found otherwise – at least for a couple weeks before the patriarchy inevitably reminds them of the reality they live in. As depressing as it is to consider the parting between the women, would it really be realistic to have a happy-ever-after ending given the 18th century conditions for queers? Unfortunately yet pragmatically, I think not.

So despite SNL calling Marianne and Héloïse’s budding romance “the world’s saddest flirting,” we are left feeling love and despair for their circumstances. The multifaceted dimensions of the queer lens guides our eyes and hearts to understand queer desire with a new perspective, even when queer cinema shifts to lesbian period drama trends.

Bibliography

Photos:

Fig. 2. Site:

Fig. 3. Site:

Image Address:

Fig. 4. Site:

https://www.tvguide.com/movies/portrait-of-a-lady-on-fire/2000203733/

Image Address:

Fig. 5. Site:

Image Address:

Texts:

Bianco, Marice, Ph.D. “In ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire,’ a feminist politics of love.” Women’s

Media Center, February 27, 2020. https://womensmediacenter.com/news-features/in-portrait-of-a-lady-on-fire-a-feminist-politics-of-love.

Chan, Jeremy. “Unprocessed thoughts: Céline Sciamma’s ‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire.’” Literally

Left-Handed (blog), February 26, 2021. https://literallylefthanded.com/2021/02/26/unprocessed-thoughts-celine-sciammas-portrait-of-a-lady-on-fire/#:~:text=There%27s%20not%20much%20dialogue.,latter%20half%20of%20the%20film).

Dawson, Leanne. “Introduction: Queer European Cinema: Queering Cinematic Time and Space.”

Studies in European Cinema 12, no. 3 (2015): 185–204. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17411548.2015.1115696.

O’Falt, Chris. “‘Portrait of a Lady on Fire’ Cinematography: The Perfect 18th Century Digital

Painting.” IndieWire, February 28, 2020. https://www.indiewire.com/features/craft/portrait-of-a-lady-on-fire-cinematography-claire-mathon-celine-sciamma-1202214143/.

Petkova, Savina. “Regardez-moi: Brush Strokees and Visibility in Portrait of a Lady on Fire.”

Girls on Top (blog), February 28, 2020. https://girlsontopstees.com/en-us/blogs/read-me/regardez-moi-brush-strokes-and-visibility-in-portrait-of-a-lady-on-fire.

Saturday Night Live. “Lesbian Period Drama – SNL.” Uploaded April 11, 2021 to YouTube, 2:56.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XgaLlP0xmqE.