Spread along Buford Highway, Plaza Fiesta is a 33,000 m2 shopping mall which aims to replicate the atmosphere of Mexican traditional markets—it is described on its official website as “the heart of one of metro Atlanta’s most diverse communities”. It is set in the city of Brookhaven, which has a significant Latin American foreign-born population: the U.S. Census Bureau’s five-year ACS estimate from 2021 indicates that 53% of the foreign-born population and 11% of the total population in Brookhaven stems from Latin America. While the stores in Plaza Fiesta mostly sell items with a utilitarian value (food, clothing, tech…), a few establishments provide their customers with home entertainment and cultural products: Cine Latino sells inexpensive (roughly $7) copies of mainstream movies, and the community-oriented library Fiesta de Libros lends children’s literature. The cultural practices of immigrant communities (whether on the production or the consumption side of it) were the focus of Art in the Lives of Immigrant Communities in the United States, a collection edited by DiMaggio and Fernández-Kelly (2010) in which they note that scholarly accounts of immigrant lives usually underestimate the significance of art:

The absence of research on this topic has been costly to both students of immigration and students of art and cultural policy. Research on the former has focused on economic and political institutions and social relations, paying less attention to the cultural life of new immigrants.” (1)

The present study seeks to explore the multilingualism of art-related products in Plaza Fiesta through two different types of media (DVDs and books), as well as the location that showcases them. I hope it sheds light on how the cultural landscape reflects the language practices of linguistic minorities and how it might differ across age-specific cultural markets (the DVD stand includes content targeting adults while Fiesta de Libro specifically provides children with “age-appropriate” content).

As previously noted, DVDs and books were the bulk of the material I researched. For time-related reasons, I did not collect data about the DVDs inside the Cine Latino store and rather looked at the DVDs exposed on a stand in front of the shop; I expect this sample to reflect the cultural products that are to be found in the shop (Fig. 1). I tried to be as efficient and expeditious as possible, so as to let the shop operate as usual. My research of Fiesta De Libros was especially limited, considering the library happened to be closed. I still managed to view the contents of the store through the metallic grate.

I used a simple notebook, using a different page for each category—Spanish-only titles, Spanish titles with some English, English titles with some Spanish, English-only titles. I divided each page into two parts: one for the DVDs in front of Cine Latino and one for the books in Fiesta de Libro. My notation was fairly simple in that I simply tallied how many examples of each title were present. Nonetheless, I also used the other side of each page to write about instances that I found particularly noteworthy, which proved especially useful in the case of Fiesta de Libro where eye-catching examples were at the core of my data.

The DVD stand in Plaza Fiesta featured 83 products, with at least one product pertaining to each category. The results can be summed up as follows:

| TYPE OF MEDIA | NUMBER OF DVDS | PERCENTAGE | EXAMPLE |

| Spanish-only titles | 35 | 42% | La guerra del planeta de los simios |

| Spanish titles with some English | 7 | 9% | La Vida es bella (Life is Beautiful) |

| English titles with some Spanish | 11 | 13% | Under the Same Moon (La Misma Luna) |

| English-only titles | 30 | 36% | Scarface |

The DVD stand featured films of all genres and for every sensibility and age—from children’s animated movies to horror flicks. Most DVDs were releases of Hollywood productions, but Latin American films could also be found (e.g. Amores Perros by Academy Award-winning director Alejandro G. Iñárritu).

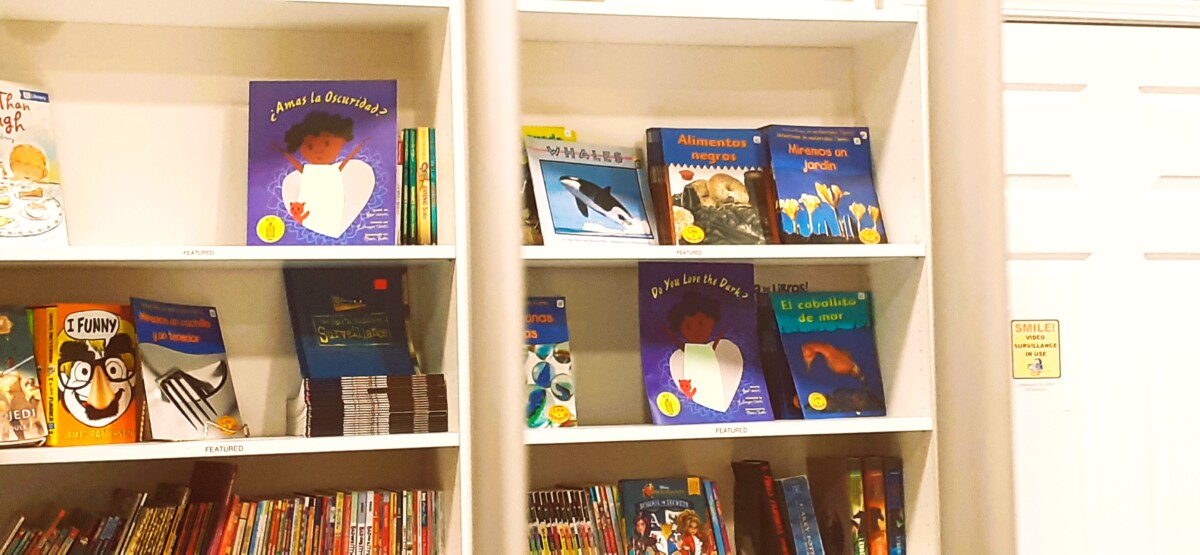

In the case of Fiesta de Libro, I had to limit myself to the most conspicuous displays of “books”: large printed reproductions of book covers that were showcased on the top bookshelves. This resulted in a small sample of 8 books (2 books in Spanish and 5 books in English and one bilingual book, albeit with an English title). Among the books in Spanish, I noted a translation of Dr. Seuss’ Green Eggs and Ham (now Huevos verdes con jamón). In order to expand my data collection, I gathered information on some non-artistic elements of the library that aimed to guide its potential users: the larger sign indicating in broad terms how the library functions was written both in Spanish and English, in a similar font size but with a different color for each language (navy blue for Spanish, as in the title of the sign, and orange for English). Conversely, the “Sistema de Honor” sheet was written exclusively in Spanish and in a much somber layout. The material I have gathered also includes the books that I could discern on the other shelves of the library (Fig. 2). Most books in Spanish seemed to be direct translations of the Read and Learn collection (now “Lee y aprende”) that was published by Heinemann—a “publisher of professional resources and a provider of educational services for teachers” (“About Heinemann”). In some cases, a Spanish book was a direct translation of an English book that was also present in the shop (e.g. Maya Lawrence’s Do You Like the Dark? and its translation ¿Amas la Oscuridad?). Overall, the vast majority of books in Fiesta de Libros were written in English.

What struck me about the DVDs when looking at the stand was that they seemed to have been produced informally, lacking the glossy look that official home video releases generally have. In his book Locked Out: Regional Restrictions in Digital Entertainment Culture, Elkans (2019) notes how the circulation of region-free DVDs and, ultimately, bootleg DVDs allows for a more bottom-up circulation of artistic products that both reflects and influences their customer’s cultural practices: “By serving particular, localized, and usually ethnically specific populations, diasporic video stores are saturated with and help structure the cinematic tastes and broader cultural matters of the surrounding community” (p.135). The predominance of Spanish content on the DVD stand seems to reflect how implanted the language is in the broader community, with both adult and children entertainment being featured in the Spanish language (such as the Stephen King adaptation Ojos de Fuego (Firestarter) and the Disney animated film Tinker Bell y la bestia de Nunca Jamás (Tinker Bell and the Legend of the NeverBeast)). This might imply that the language is spoken—or, at least, understood—across generations.

On the other hand, the predominance of English books in Fiesta de Libro, as well as the presence of English on the gaudy, child-oriented sign (Fig. 3) seems to hint at the mostly English cultural landscape of second- or third-generation immigrants.

Conversely, the more sober honor system sheet (Fig. 4), probably addressed to the children’s parents, was entirely written in Spanish, which might imply that the Spanish language is the best medium to convey information to the adult population.

I also noticed that the books in English that were showcased on top of the bookshelves were often primarily concerned with the immigrant experience and the preservation of Latin American culture: Amy Novesky’s Me, Frieda, Duncan Tonathiuh’s Diego Rivera: His World and Ours, the bilingual 3,585 Miles to be an American Girl and Maria Marquardt’s young adult novel Dream Things True. This seems to reflect the need for aspirational children’s literature intended for a Latin American audience. At the same time, it might hint at broader trends in the publishing industry. In her 2021 Newsweek article “Writers of Color Are Being Pigeonholed Into Writing About Race and Identity”, Groft (2021) deplores that the overwhelming majority of published books by people of color are centered around a limited set of subject matters:

…when I looked at the author-speaker lineup for the week of October 23-31 [of the Texas Book Festival], I was heartened to see it included many wonderful Black, Hispanic, and Native American authors, as well as a few from Bangladeshi, Chinese, Indian, and Iranian backgrounds. Yet when I reviewed the stories by these authors, I noticed that over 75 percent of them were about race and identity.

It is not entirely surprising that the publishing industry would pick up its general trends and sanitize them for the children’s market. Still, it raises the question of how comprehensively Latin American experiences are depicted in children’s literature and whether second-generation immigrants are provided with diverse-enough stories—not in terms of ethnic representation but in terms of themes, genres, tones and overall sensibilities.

Works Cited

“About Heinemann.” Heinemann, Heinemann, 2023, https://www.heinemann.com/aboutus.aspx.

DiMaggio, Paul, and Patricia Fernández-Kelly, editors. Art in the Lives of Immigrant Communities in the United States. Rutgers University Press, 2010. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hhz22. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

Groft, Desiree Prieto. “Writers of Color Are Being Pigeonholed into Writing about Race and Identity.” Newsweek, Newsweek, 18 Oct. 2021, https://www.newsweek.com/writers-color-are-being-pigeonholed-writing-about-race-identity-opinion-1639041.

Elkins, Evan. “Region-Free Media: Collecting and Selling Cultural Status.” Locked Out: Regional Restrictions in Digital Entertainment Culture, vol. 14, NYU Press, 2019, pp. 119–48. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv12fw629.8. Accessed 12 Apr. 2023.

“Home.” Plaza Fiesta, Plaza Fiesta, 2022, https://plazafiesta.net/.

3 Comments

Add Yours →As seen in the table, the Spanish titles consist of 42% while the English title consisted of 36% . I think this makes sense, since the demographic consists of a diverse population, with mainly Spanish speaking individuals, but English is necessary to expand the business’ target audience.

A great analysis of entertaining media and language at Plaza Fiesta! It was so interesting to learn about the types of books, and what languages they were printed in, available at Plaza Fiesta.

Really insightful dive into a niche linguistic subject, which should be further examined due to the role of media in childhood language development. I liked how despite the broad diversity in authorship for these books, the homogeneous subject matter reflects a sort of commodification and pigeonholing of diverse experiences. I would like to see how this looks to a young audience growing up when most of the English books published by diverse authors are about the racial experience rather than say giving a mouse a cookie, or how this affects heritage language retention in future generations.