Introduction

Plaza Fiesta, a shopping mall situated on Buford Highway houses an incredibly ethnically and racially diverse community along a stretch of the seven-lane highway, Georgia State Route 13. Its technical address is located in Brookhaven/Dekalb County, Georgia. Drawing from Census Data this plaza is centered in a community that has a large Spanish-speaking population with leading countries of origins being Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, Honduras, and Spain.

Because of the large Spanish-speaking population in the area, I was interested in examining the visible and audible languages in Plaza Fiesta. Specifically, I focused on the main drag/aisle and food court of the Plaza in order to find out which languages the consumers versus the vendors preferred. I was particularly interested to see if there was a preference for bilingual language use in order to understand the importance of multilingualism in commercial spaces in Atlanta and in diversifying markets.

Previous scholarship that models this question can be found in studies like Pappenhagen et al’s (2016) investigation of ‘Linguistic Soundscaping’ in Germany. They were curious about when and why “immigrant languages” were used versus German. They discuss the implications of language to shape society and public spaces.

Methods

My criteria for counting signs was “any piece of written text within a spatially definable frame” (Backhaus 2006: 55). This meant that, in addition to formal and official signage on vendors’ store fronts, I was also looking for signs that were taped onto the windows of stores or on stick-it notes.

Entering the Plaza, I walked for about 10 minutes through the main aisle, taking about three routes back and forth while taking photos and noting conversations as I went along.

Some difficulties I encountered were taking photos with people in the shot who did not consent to this photography. I tried my best to take photos discreetly and respectfully, especially when workers or children were in the store.

For the conversations, I noted the conversations I heard during this route and also during the 25 minutes I spent in the food court. Any time I heard Spanish between a vendor or consumer or between private parties, I would mentally take note of this, afterwards, quantifying them on my phone. This meant that even if I passed by a party of Spanish speakers, I counted that as a conversation in Spanish.

Aspects of the site that I did not include were the digital moving signs on the televisions scattered around the Plaza; these were mainly advertisements.

Results

Visual landscape

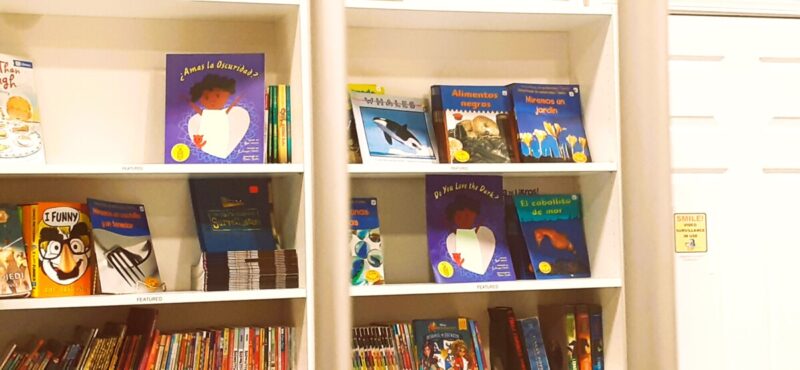

For the visual landscape, I saw a wide range and mix of bilingual and monolingual signs, both in English and Spanish. Figure 1 captures this variety of signage. Signs that were official and immovable from the space like the Non-Smoking sign were completely in English. That contrasted with posters custom made for the stores that were bilingual. Or, if they were the name of a store that was not necessarily in Spanish or needed translation, these official signs were solely in English.

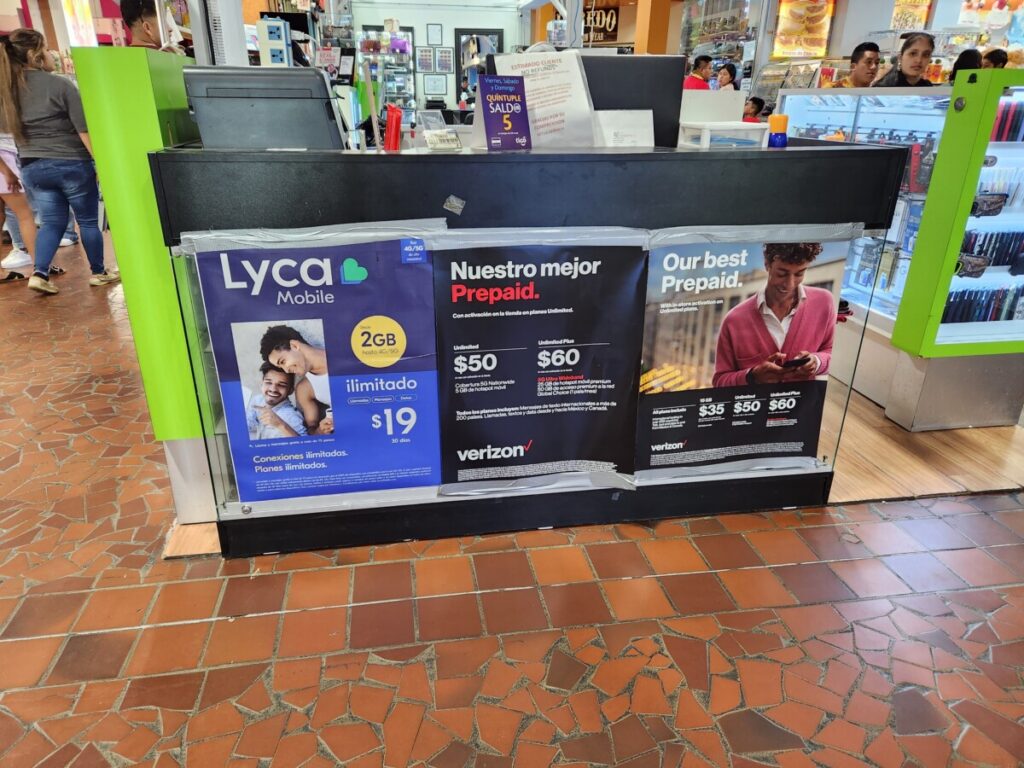

Bilingual posters typically offered services for beauty products and services or phones. I took note of monolingual posters placed next to each other making a bilingual environment but without the codeswitching in the same contextual frame. I primarily saw this with the vendors in the middle of the aisles, typically selling phone plans or makeup services as well (Figures 2, 3, and 4).

Figure 4

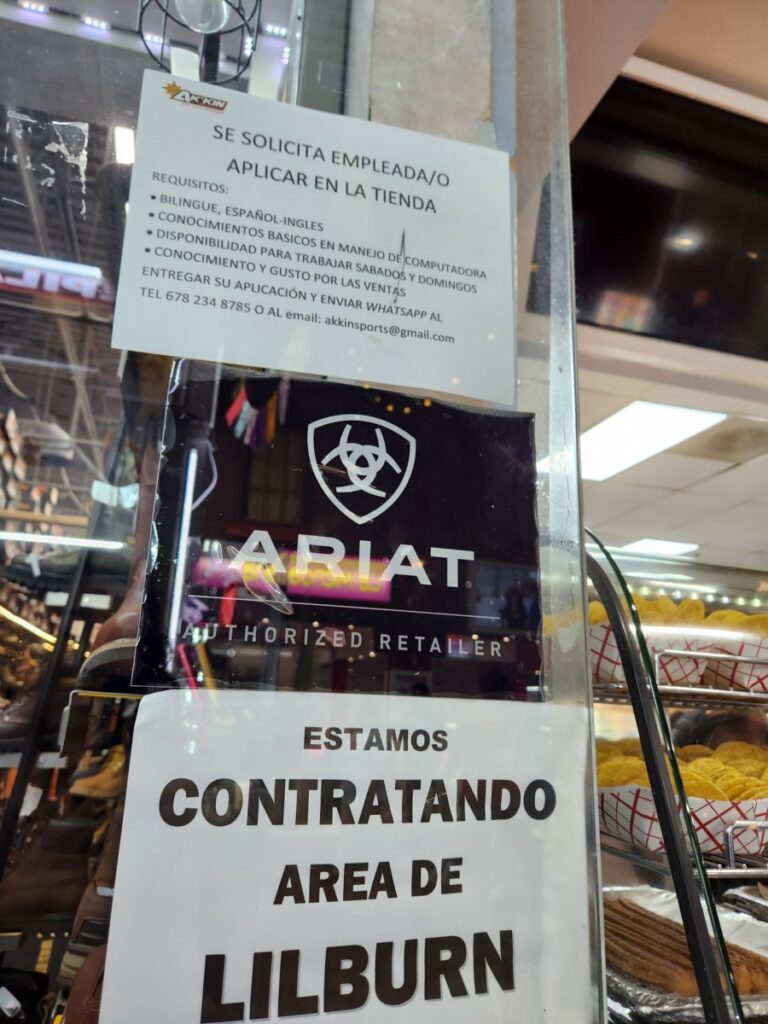

Some highlights were the smaller, informal signs advertising work that were found on printed paper that could be easily removed; the preferred language was Spanish. One of the more common signs of this type were “No Touch” signs that had “No Tocar” in the preferred and more salient position at the top of the sign and above their English translation (Figure 5).

Others also showed salience and preference for Spanish over English, such as some monolingual and informal signs reading “Hacemos pagos de metro,” advertising for employment with the assumption that its monolingual Spanish sign would attract completely fluent Spanish speakers (Figures 6 and 7).

One exception to this pattern of informal signs being monolingual and Spanish was an anti-ICE, pro-immigrant sign, taped onto a seemingly random pole in a nearby aisle. This flyer was completely in English, perhaps intended for a monolingual audience yet it exists in a Spanish dominant space (Figure 8).

Aural landscape

Most, almost all, conversations were conducted in Spanish, either between vendors and consumers or between personal friends and families. For English, I heard only seven conversations or phrases in the entire hour I was in the Plaza Fiesta. Two of them were interactions between me and another stranger, one where I apologized for bumping into them and the other when the cashier asked me for a receipt. One of the conversations in English was between a father and son (middle-aged and youth) but the others were between solely between youth. In other words, there was never a conversation in English between speakers who could be considered as adults. The English conversations were conducted between same parties and never between consumers and vendors; all of these interactions were in Spanish, even the announcement of meals in the food court would be announced first in Spanish and then occasionally in English.

Discussion

Based on this visit to Plaza Fiesta, Spanish plays a clear informational role in this space. Its use carries little overt symbolic value; Spanish serves as the lingua franca of Plaza Fiesta, utilized by its majority Spanish-speaking population in the day-to-day functionalities of the market that are mainly transactional between businesses and consumers. Arguably, English is equally informational for people who might not be Spanish speakers but is less present. Its presence not only implicates Plaza Fiesta’s general existence in America but also that it is not exclusionary towards the patronage of monolingual English speakers.

The saliency of Spanish in more informal signs, though, reveals that Spanish as the dominant and preferred language. There is an assumption that all employees can and will speak Spanish with almost all of their customers and that products will culturally also be in Spanish language and useful for those who desire native Spanish products.

For the aural landscape, again, unlike some studies that find that the dominant mother country language is used between vendors and consumers and then paternal home languages used between the consumer parties (e.g., Pappenhagen, et al, 2016), Spanish is the dominant and preferred code of communication of all conversation types, colloquially and formally.

For further research and expansion, as mentioned in the Methods section, it would be important to investigate the wardrobe landscape. Even though I heard almost only Spanish, a lot of the clothes worn by consumers and passersby contained or displayed English. Or their clothes referenced items, such as local sports teams, that indicated their location in Atlanta. Furthermore, although I did not count the language used on the TV screens placed throughout the Plaza, I think with the rise of technology and moving advertisements, further research into language use in the media landscape could illuminate the flexibility and fluidity of language in changing and burgeoning landscapes.

2 Comments

Add Yours →I thought you did a very insightful and comprehensive investigation into the soundscape and signscape of Plaza Fiesta. It was an interesting method to focus on conversations present in the location as well as signage because that allows you a deeper insight into the lived space of this community. I also thought your observations of the salience of English as the language of preference in official signage relating to the space as opposed to Spanish as the language of preference for personal and promotional signage was intriguing and you provided a good analysis of that. In addition to possibly looking into clothing and the language on tv monitors, I think an interesting possible future direction for this project would be looking into the soundscape outside of conversations and including things like radio, music, or announcements. Overall, this project was very well done!

Your project provides an insightful analysis of the linguistic landscape and practices in a shopping mall located in an ethnically and racially diverse community. The focus on the use of language in the main aisle and food court of the plaza, as well as the visual and aural landscapes, allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the role of language in this commercial space. I also liked that the findings that Spanish is the dominant and preferred language in the plaza is not surprising given the demographic makeup but the lack of English conversations between vendors and consumers struck me. Overall, your project provides an important contribution to the study of linguistic diversity and multilingualism in commercial spaces in diverse communities.