Introduction

Plaza Fiesta, a hub of Spanish-language multiculturalism, located on Buford Highway in Atlanta, Georgia, has a particularly rich semiotic landscape to explore. Our focus was the visual landscape outside the Plaza, specifically the bumper sticker landscape on cars in the parking lot. Bumper stickers have not been a common theme in Linguistic Landscape research, however previous studies that have investigated this landscape demonstrated that bumper stickers are a unique form of self-expression which allows drives to share their opinions, beliefs, and even identities succinctly to other drivers (Jaradat, 2016). Jaradat (2016) investigated car bumper stickers in Jordan and focused “mainly on the themes of the stickers” (p. 253). The researcher hypothesized that car bumper stickers in Jordan “reflected a wide range of topics including social, economic, and political” (p. 253). As such, we were motivated by the following research questions while investigating the “stickerscape” of Atlanta residents who frequent Plaza Fiesta:

- Do the bumper stickers visible on cars in the Plaza Fiesta parking lot reveal specific social, economic, and political topics of interest to consumers at Plaza Fiesta?

- Do bumper stickers, as a means for outward expression, act as a possible proxy for the lived space of the residents in the community, which under normal circumstances would be hard to gauge without direct interaction with the residents?

- Does the visible landscape, as manifested in the bumper stickers, reflect accurately the multilingualism in Atlanta?

Methods

Our data set was gathered on a busy Saturday afternoon in the early spring, when both the Plaza and the surrounding parking lot were at full capacity, thus ensuring a large sample size for the study. We initially began by walking together and gathering data as a group but quickly realized we would be more efficient and less conspicuous if we each worked alone. Part of the reason why this was necessary was because our initial idea to tally different categories of bumper stickers did not account for the diverse range of stickers we saw. We instead opted to take photos of every sticker, which drew more attention to our data collection. We captured images of every car that had bumper stickers on it in all sections of the parking lots surrounding Plaza Fiesta.

Cars were selected for the dataset if they had at least one discernible sticker somewhere on the vehicle; it did not necessarily have to be on the bumper. For cars with multiple stickers, individual stickers were counted and categorized separately based on the identifiable borders that separated them, despite being on the same vehicle. In cases where multiple stickers seemed to be making up a larger image or message, they were counted as a single sticker. For example, in Fig. 1 below, we identified the three words “Hanging Dog, NC” as one sticker, the images constituting a moon and tree as one sticker, and the two individual stickers of bear paws as a singular set of paws.

Figure 1

After the initial collection of the data, the images were sifted through and tallied to determine the number of cars and number of stickers. Then, each each sticker was categorized into different categories. The broader categories we identified were based on the Jaradat (2016) study which observed “social,” “economic,” and “political” types of stickers. We decided to include an additional category known as “other” to encompass stickers that we deemed fell outside the initial three categories. Within these broader categories, we also identified several more specific and descriptive subcategories to best capture the range of ideas and concepts present in the stickers. Stickers were identified as “social” types if they generally referred to people, places, and things that presumably foster some type of social connection for the driver and for the viewer. This can include stickers referring to family (Fig. 2), a location or tourist site, a reference to popular media such as famous characters or people, or to other social bonds such as religion (Fig. 3), sports, and school.

Figure 2

Figure 3

Stickers were identified as “economic” if they included branding for large businesses, such as logos or slogans, or promotional material for local businesses and events generating profit.

Stickers were identified as “political” if they contained text or imagery that supported a certain political stance, viewpoint, or institution, such as the military, or if they displayed a particular political or national affiliation using flags (Fig. 4).

Figure 4

Lastly, stickers were identified as “other” if they were not able to easily fit into the categories outlined above. This includes miscellaneous images or phrases that have no apparent affiliation, such as butterflies, stars or comedic sentences, or organizations that are independent of political association and do not generate money to be considered a business, such as non-profit organizations.

In addition to identifying the types of stickers present, we also took into consideration if each sticker consisted of an image, text, or both. If the sticker contained text, we determined the language that was most dominant and noted that as the language of preference (Fig. 5). We also considered the origin of the license plates on the cars to ensure that we were surveying the local population as best as possible and also to make note of any license plates that were not local to Georgia.

Figure 5

Results

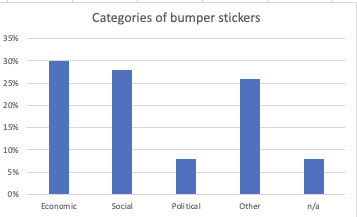

In total, our sample size consisted of 125 cars and a total of 271 bumper stickers, with an average of 2.2 stickers per vehicle. After collecting and analyzing the data, our study found that of the four major categories outlined above, the largest category was “economic” stickers which formed 30% of the observations, followed by “social” stickers which formed 28%. “Other” stickers made up 26% of the data, and “political” stickers constituted 8%. 21 of the 271 observations (8%) could not be categorized and were labeled as “unknown” or “n/a” (Fig. 6). Some cars had multiple stickers that fell into two categories but were only assigned to one category.

Figure 6

Taking a closer look into the economic category, the most frequent occurrence were ‘business’ type stickers, appearing twice as often as ‘promotional’ stickers, the other type of economic sticker. The business stickers largely consisted of big corporations such as Apple and Supreme. The most prevalent business in this category was car and truck dealerships with many vehicles often displaying stickers in support of the car manufacturing company that made their vehicle, such as Toyota, Subaru, Carmax, Carland, Texano’s trucks, and other local dealership businesses. Although the promotional type was not as common, there were several instances of stickers which promoted a local business or event that were very heavily represented in comparison to the amount of cars that had any promotional stickers present. In other words, every occurrence of the promotional stickers originated from two vehicles and thus may have mischaracterized how prevalent this type of sticker was in the Plaza Fiesta community

Investigating the political sticker category shows that a majority of the stickers belonging in this category were military or military-affiliated. The vehicles consisted mostly of stickers for the U.S. Marines, often accompanied by text saying “the proud parent of a U.S. Marine” or “proud mom of a U.S. Marine”. There were also several instances of stickers for the U.S. Army, Navy as well as for combat medic support, but they were usually only images of the logos of these branches of the military rather than actual text. Flags were the next most common sticker type and were almost always images instead of text. The flag stickers were typically used to show support for a country and were mainly American or Mexican flags. One interesting observation is the prevalence of the blue line U.S. flag which is often associated with the Blue Lives Matter response to the Black Lives Matter movement. Lastly, the least common stickers seen in this category were blatant proclamations of political leanings and support, with the few instances we noted showing support for Biden/Harris and a statement saying “no farms no food”.

The social sticker category had the most variation of subcategories and as such, is not disproportionately influenced or weighed by any particular sticker type. The three most frequent observations of social stickers were affiliated with religion, school, or family. The religious stickers were overwhelmingly representative of the Christian faith and often contained imagery of crosses, rosaries, the ichthys fish, Jesus Christ, and the virgin Mary. These stickers were often just images, but whenever both images and text were present, the language observed was usually Spanish (Fig. 7).

Figure 7

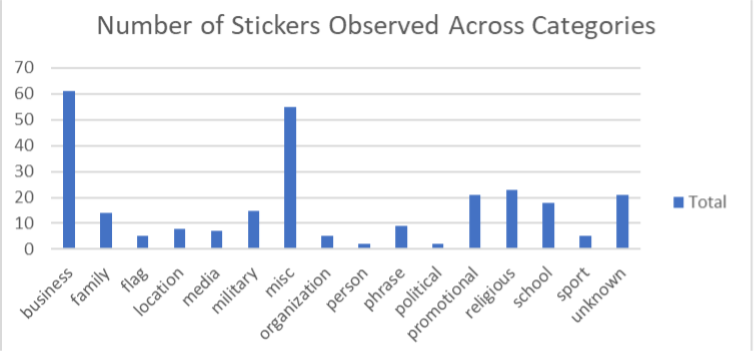

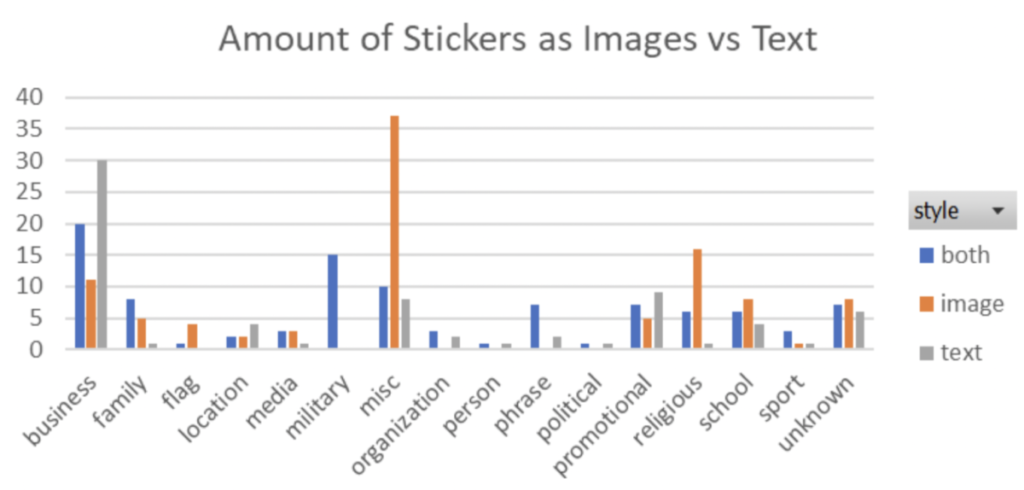

Following closely behind the religious sticker type, school-affiliated stickers were also quite prevalent. School stickers were almost always stickers that represented the school of interest using the school’s logo and were nearly always images. The schools represented through these stickers were frequently Georgia Tech and the University of Georgia, although there were also University of Houston and Notre Dame stickers. Although most of the stickers in this subcategory were university stickers, there were a couple instances of stickers for high schools or institutions at a lower educational level. Family stickers in this subcategory were typically cartoon images of a family and declarations of the family present in the vehicle, with the most salient example being stickers saying “baby on board”. Location stickers, like Michoacan (Fig. 5), were diverse and spanned multiple states or even multiple countries in this instance. Sports stickers were largely in support of football, with basketball teams following behind closely as well. Lastly, popular media stickers usually referred to animated characters, such as Hatsune Miku, a well-known anime character, and Stitch from the Disney animated film Lilo and Stitch, although there were a couple instances of famous people as stickers. Figures 8 and 9 provide an overview of the distribution of the types of images and texts found on cars’ bumper stickers.

Figure 8

Figure 9

The ‘other’ sticker type was dominated by miscellaneous images and texts. These stickers were often random depictions of symbols, cartoons, and pictures that could be used in humorous or comedic ways. The phrases subcategory often consisted of text that depicted popular turns of phrase or inspirational quotes that are readily present in everyday life. One of the organizations noted in the data is El Refugio which is a non-profit organization and thus did not fit into any other category outlined above.

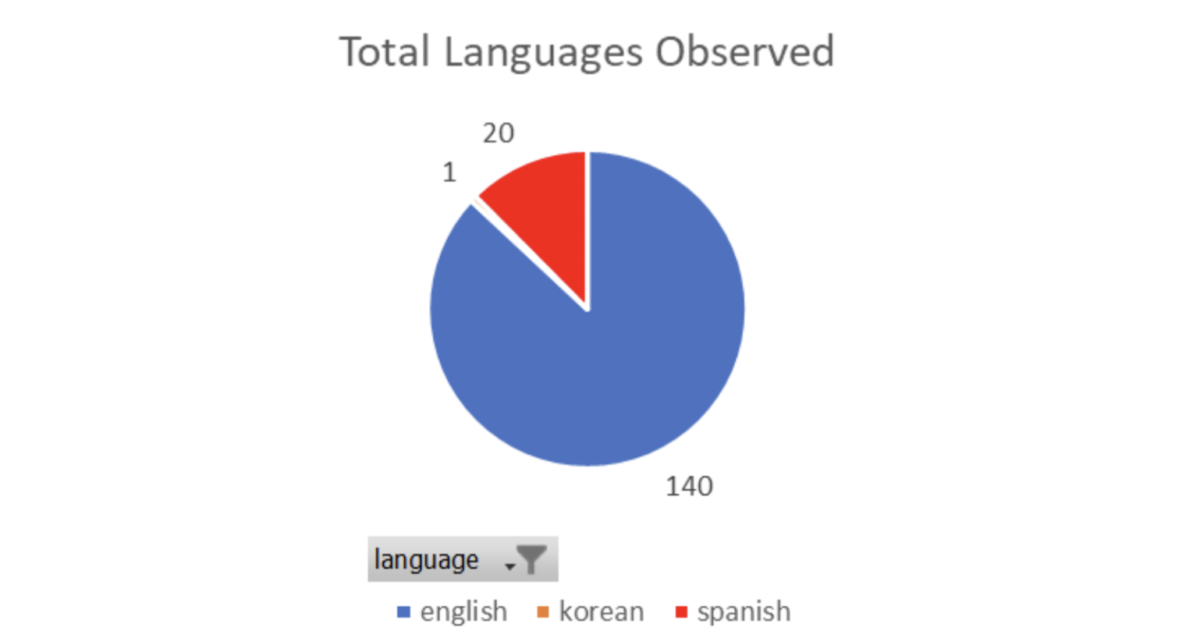

As stated by the US Census Bureau, DeKalb County’s primary languages are English and Spanish. The language of the stickers correlated with the census data since most stickers were in either English, Spanish or a mix of both (Fig. 10).

Figure 10

Discussion

Firstly, our results demonstrate a pattern that is reflective of the county’s most spoken languages. As stated by the US Census Bureau, DeKalb County’s primary languages are English and Spanish, respectively. The stickers contained mainly English language and were followed by the Spanish language.

When first organizing the experiment, the group expected to find a majority of Spanish stickers, in addition to stickers that reflected a Spanish-speaking geographical location. However, we found a select few stickers that demonstrated a connection to Spanish-speaking geographical locations, such as Mexico and Michoacán (Figure 15). In addition, only six percent of the stickers with text on them fell under the category of ‘Spanish’.

The largest category that stickers fell under was ‘Economic’. In a day and age where most advertising is digital, stickers remain one of a few tangible forms of advertisements available to businesses. Due to their low cost of manufacturing and distribution, both small and large corporations distribute stickers to customers and potential customers to advertise their products and services. A portion of the ‘economic’ bumper stickers we saw were likely received by customers and placed on their cars to demonstrate appreciation for a particular brand or business.

Furthermore, some of the stickers appeared to be placed on cars belonging to individual business owners and their employees, who utilize their vehicles to promote their businesses. One way to improve our experiment and find answers to our unanswered questions is by surveying the population and interacting further with the community in order to find the motive for such stickers and explanations as symbols. This would allow us greater access into the lived space (Malinowski, 2015).

References:

Jaradat, A. A. (2016). “Content-Based Analysis of Bumper Stickers in Jordan.” Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 7(6), 253-261. http://www.journals.aiac.org.au/index.php/alls/article/view/2937

Malinowski, D. (2015). Opening spaces of learning in the linguistic landscape. Linguistic Landscape, 1(1), 95–113.