Introduction

Public spaces are constructed not only through architecture but also through the semiotic resources that fill them. Linguistic landscape (LL) studies explore how language appears in public signage and other forms of communication to reflect identity. However, there is often a gap between what is seen and what is heard. This project investigates the relationship between Emory University’s signscape and soundscape to understand how multilingualism is experienced, represented, or left out in public spaces.

Several studies have shaped the framework for this project. Specifically, Pappenhagen et al. (2016) critique the visual bias of traditional LL research and introduce the concept of the linguistic soundscape as a way to see how spoken language creates meaning. In their study of the St. Georg district in Hamburg, Germany, they show how minority languages like Turkish and Arabic were frequently spoken, although being almost absent from the visible landscape. In addition, Spolsky (2020) argues that public signage functions as a form of language policy, reflecting who has the authority to speak and be seen in public spaces. He emphasizes that signage reinforces dominant languages and ideologies, even in linguistically diverse environments. These scholars have inspired my focus on the disconnect between written and spoken language at Emory.

This project is situated at Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia. According to Emory International Student and Scholar Services, “Emory is home to nearly 3,300 international students and more than 1,000 international scholars from over 100 countries” (Student & Scholar Data: 2024 IIE Open Doors Report, based on Fall 2023 data). As an international student myself, I have experienced how Emory’s rich linguistic diversity is audibly present in everyday interactions, but not always visibly reflected in the signage around campus. This contrast raises questions about how the university’s public language practices reflect, or fail to reflect, the realities of its student body.

Therefore, this project aims to analyze whether Emory’s visible signage remains predominantly monolingual while its soundscape reflects a more multilingual reality, and whether some groups remain linguistically invisible in the university’s public representation. The goal is to examine the relationship between institutional language practices, student experiences, and linguistic inclusion in shared university spaces.

Method

To investigate the relationship between Emory University’s signscape and its soundscape, I collected two types of data: a signage audit and a series of soundwalks.

Signscape:

Following Backhaus (2006, p55), this study defined a sign as “any piece of written text within a public space, excluding private or personal communication.” This included permanent signs (e.g., building names, university-issued signs), temporary signs (e.g., posters, flyers), and directional signs (e.g., restroom signs). I recorded data by taking notes and organizing them into a chart by location and language. The signage audit was conducted over two days (April 14 and 15, 2025) between 11:30 a.m. and 2:00 p.m.

I surveyed signs in four central campus locations:

- Callaway Center:

- The primary classroom building for humanities courses

- Student Center:

- The large multi-purpose building that has the main dining hall, a cafe, and meeting rooms for students and student organizations

- Robert W. Woodruff Library:

- The main central library on campus

- The Quad:

- The large green open area at the center of campus

I chose these areas because the student population is large, and these areas have the highest foot traffic of any locations on campus. In each location, I recorded:

- The total number of signs

- The languages used on each sign

- Whether the sign was institutional or student-created

Soundscape:

I conducted 15-minute sound walks in each of the same four campus locations. These were completed during class breaks when public interactions are most likely. No recordings were made for privacy reasons. Instead, I took detailed field notes on what languages I could identify, and the context in which they were being used (e.g., casual conversation, phone call, group work).

I listened for:

- The number of different languages spoken

- Approximate number of speakers per language

- Evidence of code-switching or translanguaging

Results

1. Signage is mostly Monolingual

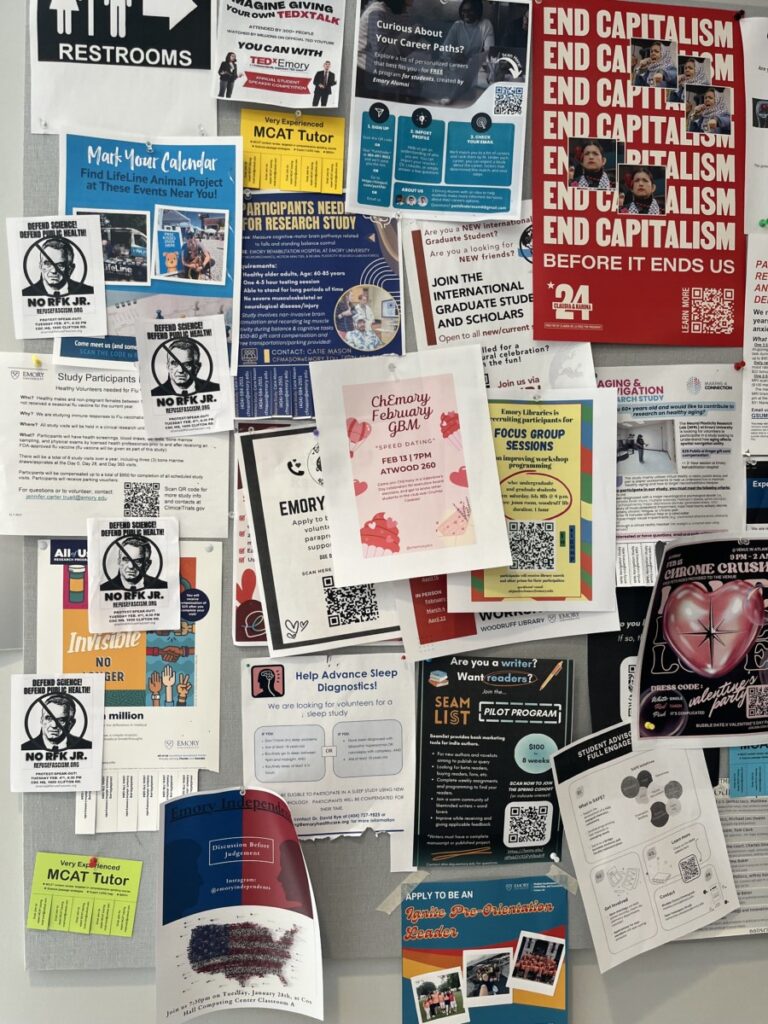

Across the four campus locations, I recorded 101 signs (see Figures 1-5 for examples).

- English only: 82 signs (81.19%)

- Bilingual: 16 signs (15.84%)

- Chinese & English

- Spanish & English

- Portuguese & English

- Monolingual Non-English: 3 signs (2.97%)

Chart 1. Signage Language Distribution by Location

| Location | Total Signs | English Only | Bilingual | Monolingual Non-English |

| Callaway Center | 29 | 23 (79.3%) | 5 (17.2%) | 1 (3.4%) – Spanish |

| Student Center | 18 | 15 (83.3%) | 3 (16.7%) | 0 (0%) |

| Woodruff Library | 21 | 19 (90.5%) | 2 (9.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| The Quad | 33 | 25 (75.8%) | 6 (18.2%) | 2 (6.1%) – Chinese & Spanish |

| TOTAL | 101 | 82 (81.2%) | 16 (15.8%) | 3 (3.0%) |

2. Soundscape is multilingual and fluid

During the 15-minute class breaks at each location, I identified 6 different spoken languages:

- English (62.03%)

- Mandarin (10.76%)

- Korean (6.33%)

- Hindi (4.43%)

- Spanish (4.43%)

- Swahili (0.63%)

- Code-switching (11.39%)

Chart 2. Spoken Languages Observed During Soundwalks

| Location | English | Mandarin | Korean | Hindi | Spanish | Swahili | Code-switching | Total |

| Callaway Center | 14 54% | 3 11.5% | 1 3.8% | 1 3.8% | 2 7.7% | 1 3.8% | 4 15.4% | 26 |

| Student Center | 29 63% | 6 13.0% | 3 6.5% | 2 4.3% | 1 2.2% | 0 0% | 5 10.9% | 46 |

| Woodruff Library | 20 63% | 4 12.5% | 4 12.5% | 1 3.1% | 0 0% | 0 0% | 3 9.4% | 32 |

| The Quad | 35 67.3% | 4 7.7% | 2 3.8% | 2 3.8% | 3 5.8% | 0 0% | 6 11.5% | 52 |

| Total | 98 62% | 17 10.8% | 10 6.3% | 7 4.4% | 7 4.4% | 1 0.6% | 18 11.4% | 158 |

Based on the data, I found that code-switching (11.4%) appeared consistently across different campus spaces, especially among international students. In many cases, students would start a sentence in English and then switch to their native language during conversation when talking to peers from the same background.

As a result, my data suggests that the soundscape is consistently more linguistically diverse than the signscape. Multilingualism is alive in casual, spoken exchanges, even when it is almost invisible in formal, written signage. Although English was the dominant language across all four locations, its presence was slightly lower in the Callaway Center (54%) compared to other areas like the Student Center and Woodruff Library (both 63%) and the Quad (67%). Overall, there were no major differences across locations in the general pattern of English dominance with multilingual speech diversity.

Discussion

This project aims to explore the relationship between Emory University’s visible signscape and its soundscape, and whether there is a gap between the two, which reflects a disconnect between institutional language practices and the linguistic diversity of the student body. Based on the data collected, the results support the initial hypothesis: Emory’s visible signage remains predominantly monolingual, while its soundscape reflects a much more multilingual reality.

The findings align with the previous scholarship in the field. Pappenhagen et al. (2016) argue that public signage often privileges dominant languages and erases minority voices, even in multilingual settings. Similarly, Spolsky (2020) sees signage as a reflection of power structures, shaped by institutional decisions to decide which languages are made visible. At Emory, both top-down institutional signage and bottom-up student-created signage overwhelmingly favor English. This pattern suggests that English is seen as the default language for public communication, regardless of who produces the sign. Meanwhile, the diversity of languages heard in the soundscape suggests that multilingualism is an active part of student life.

The results showed that over 80% of signs were monolingual in English, and fewer than 3% displayed only non-English languages. In contrast, the soundscape included six different languages, and code-switching was observed in 11.4% of interactions. Code-switching can be seen as a marker of multilingual identity, often associated with international students, heritage speakers, and second-generation bilinguals. On one hand, these students’ ability to shift easily between English and other languages might suggest that English signage is sufficient for daily communication, potentially justifying the institution’s reliance on a monolingual signscape. On the other hand, the noticeable presence of code-switching indicates an active multilingual reality that remains largely invisible at the institutional level. Although institutional signage reflects top-down monolingual policies, most student-created signage is also monolingual. This shows that English is considered the default language for public communication. This is possibly because English is the language most accessible to a wide audience, or because students are unconsciously mirroring institutional norms that prioritize English. Thus, both top-down and bottom-up signage contribute to reinforcing English as the dominant public language at Emory. This phenomenon suggests a need for more inclusive language representation in public signage to better acknowledge the linguistic diversity of the student body.

To pursue these issues further, subsequent studies could be expanded to include the following components. First, the signage audit was limited to four campus locations, and other areas may reflect different language practices. Additionally, the soundscape observations were conducted during several short class break periods and may not fully capture the linguistic activity on campus. Furthermore, I was the only person recording the soundscape audit, and I might have missed or misidentified languages I don’t speak or recognize. Thus, future research could expand the range of times and locations for data collection and involve collaborators from different linguistic backgrounds to provide a more comprehensive analysis.

Despite these limitations, the findings are meaningful. The result suggests that while Emory’s student body is linguistically diverse, this diversity is not fully reflected in the university’s visual space. When certain languages are absent from public signage, it can contribute to feelings of exclusion or invisibility among students who speak them. This mismatch between the soundscape and the signscape subtly reinforces dominant language ideologies, showing which voices are recognized and which are marginalized. More broadly, it raises questions about language policy, representation, and belonging in society. Both top-down institutional signage and bottom-up student-created signage overwhelmingly favor English, which shows that monolingual norms are embedded across different layers of campus communication. Emory has an opportunity to embrace the multilingualism already present within its community, not only through its student population but also through its public-facing spaces. This would be a step toward greater linguistic and cultural inclusivity.

Bibliography

Emory International Student and Scholar Services. Facts & Figures. (n.d.). https://isss.emory.edu/about/facts_and_figures.html

Spolsky, B. (2020). Linguistic landscape: The semiotics of public signage. Linguistic Landscape, 6(1).

Peter Backhaus (2006) Multilingualism in Tokyo: A Look into the Linguistic Landscape, International Journal of Multilingualism, 3:1, 52

Pappenhagen, R., Scarvaglieri, C., & Redder, A. (2016). Expanding the linguistic landscape scenery? Action theory and linguistic soundscaping. Negotiating and contesting identities in linguistic landscapes (pp. 147–162). Bloomsbury Academic.