This week we began to tease out elements of of ‘the body’ in the title of our course. On Monday we engaged questions of sinfulness, Christianity, relationality, race, imperialism, colonialism, and coloniality to ‘flesh bodies’ with Mayra Rivera. On Wednesday we read two very different pieces by Padilla and Barreto that added questions about submission, family, self-negation (or abnegation), ethnicity, history, gender, and comunidades de fé, among others. The story of the Guadalupe (which we shall return to when we discuss migration and the diasporic communities of Guadalupanas in the US and México) illustrated the complex network of angles and perspectives that must be engaged to grasp the purity and strength of Latinas in Religion.

With this in mind, write a reflection on which of these issues, questions, and stories inspired a better understanding of ‘the body’ of Latinas in religion.

Try to post your reflection by Saturday at 8PM, remembering that this is a suggested deadline, so you can then pass the page and move on to the next set of questions we’ll contemplate next week.

13 replies on “31 August-2 September. Fleshing Bodies”

This past week, after reflecting on the readings, discussion in class, and videos, I have gained a better understanding of ‘the body’ of Latinas in religion. The reading, “Latinas and Religión: Subordination or State of Grace?” by Laura M. Padilla particularly struck me because it gave more historical background of the role of religion in Latinas and “deconstructed” Latinas, culture, and religión. In particular, I found Padilla’s statement about religión seen as a paradoxical form of strength and subordination to be interesting (974). Padilla states that Latina cultural tendencies are accepting their “fate of suffering with dignity…” which is rooted from the belief that it is God’s will (ideas of predestination etc.) (974). This “acceptance of suffering” could be seen through the documentary about the femicides women endured in Honduras. Something I found astonishing is the fact that much of the violence committed against women (body and mind) were committed by family members (husband etc.) However,

another prevailing belief is the reverence for the strength of family (which may also have been influenced from religión; Virgin Mary etc.). Once again, a paradox of strength and oppression may be visible. However, one sees that spiritual “faith” communities or families may also play a role in providing a source of strength against such oppression.

One thing I wonder is, are the Latinas who find strength from religion the same Latinas who find religion as a system of oppression? Do those who find the strength see themselves as oppressed? Perhaps they don’t see the religión as the one who oppresses but some other force at play. Furthermore, what is “religion” mentioned by Padilla? Is it the “system” or the faith community? Is it the laws that dictate a certain belief? When Padilla states that religión is paradoxically the source of strength and oppression, are the Latinas who find strength and those who feel oppressed by religión speaking of the same meaning of religion? For instance, Padilla states that “Latinas’ God is a personal, living God with whom they converse daily—upon awakening, while driving to work, booting up a computer, reprimanding children and wondering how they will possibly get through another day..” (Padilla 978).

I find it interesting that there is “umbrella” term for religión, but the image evoked may depend on one’s personal experience or understanding of religión.

Laura Padilla’s “Latinas and Religion: Subordination or State of Grace” really helped me think about the role of resilience and strength in the religious/spiritual lives of Latinas. Padilla’s focus on how Latinas negotiate with oppressive and often suffocating structures within religious institutions as they grapple with their faith helped me interrogate how the body and the spirit/soul of Latinas have an interesting negotiation with endurance. Why do Latinas endure and struggle through the subjugating forces of the Church? Does the faith they find within these structures offer them a sense of relief or escape from the daily struggles of white patriarchal supremacy they face? How is endurance and resilience a result of living in a world with limited options of “being”? Padilla’s analysis and these questions inspired a better understanding of “the body” because she breaks down religion in a way that reveals not only how the daily lives of Latinas inform how they worship or find faith, but also explains how religion is rooted in a history of colonialism and violence. Both of these constructs are inseparable and complicate the journeys of Latinas who are trying to find possibility and faith in a world where violence and oppression feels inescapable.

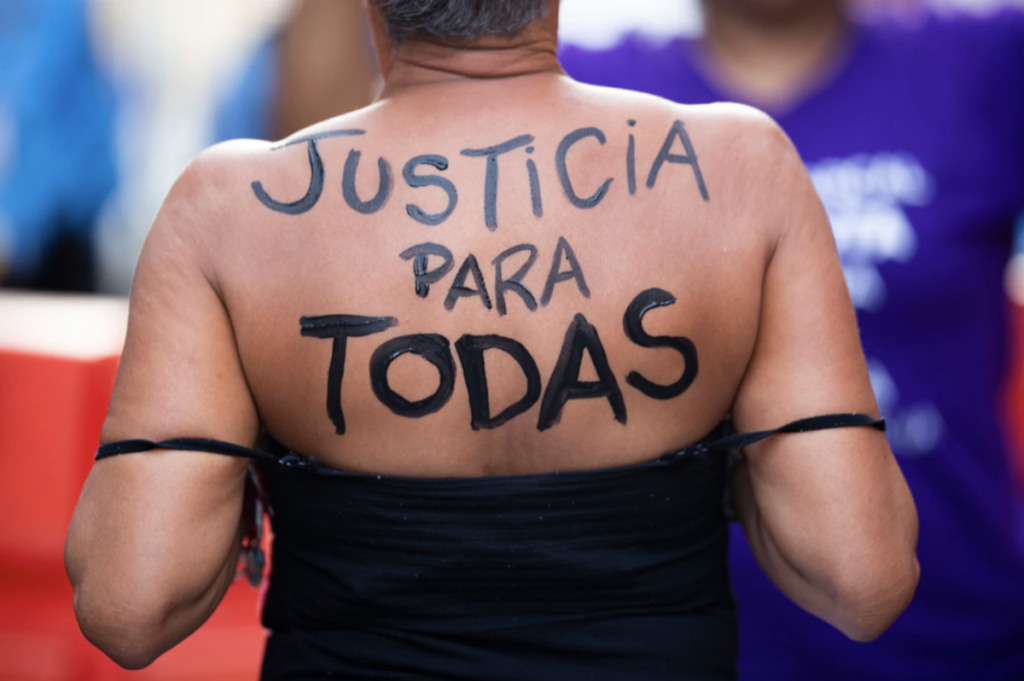

The video about femicide in Honduras really allowed me to shape my questions because it allowed me to see how our institutions of “justice” were failing Latinas who were being abused and murdered. Seeing the daily struggle and impotence that Latinas were facing allowed me to think about how a lack of faith in the institutions that are supposed to protect us could inspire a revival of hope and faith in a world that exists beyond the one our bodies occupy. Could religion be providing this sense of abstract/transcendental possibility for Latinas? The relationship between body and spirit/soul is directly connected to what we subjugate ourselves to as Latinas in order to feel whole or healed (or at least getting close to what that wholeness and healing feels like). What do we do to heal our spirits/souls in a world that dictates and controls how our physical bodies navigate?

On Monday, we were able to discuss the ways the body and flesh are seen through a religious lens and how religion, or more specifically the church, treats a woman’s body in turn. I think the one idea that best helped me differentiate flesh and body this week are the words “the flesh is weak,” and “your body is a temple”. In my understanding, flesh in religion refers to mortal things. It is more about one’s physical body and can relate to sin and death or the absence of the divine. Body, on the other hand, refers to something more. It can be a holy or unholy but has something spiritual about it. This being said, I am interested in the idea of how the church in turn may use this, flesh as a conditioning identity, to blatantly discriminate against women while still holding up traditions and faith belonging to religious figures that are women. One example that comes to mind is that the church will not always allow women to hold positions of leadership within the church yet will trust in the Virgin and follow her guidance.

I really like how Claire elaborated on how strength and subordination go together in religion. In a generalizing way and based on my personal experience, I’d say most women and Latinas would like to see more progress within religion and the church when it comes to defining a woman’s role. Further, I believe the church, though perhaps indirectly, has a big influence in the way a Latina’s fleshing body is treated today. We see this in countries like Honduras where many people would consider themselves religious or faithful and women explain that their bodies and their lives are worth nothing. How could an atrocity like Femicide be stopped if the police are unable to control it and the church demonstrates an ideology that women have no power and no say?

To end on a more lifted note, I think both our readings and our discussions helped with being able to deconstruct the concept of Bodies and Religion. I look forward to next week’s discussions and the new things we will learn.

I developed a better understanding about “the body” of Latinas from the reading of Mayra Rivera’s framework of the sociocultural influence on the imagery of the body, and I was able to see how that image could be played out as a source of strength and violence by the reading from Laura Padilla.

The reading from Mayra Rivera, “Introduction. Both Flesh and Not” (Poetics of Flesh) gave me an understanding of how the dynamics between language and body governs the body’s social relation. She brings to light the way representations of gender and race become systematically used to affirm social hierarchies of power. Rivera describes that flesh has been associated with connotations of sin and lust, but minorities and women have also been linked to living according to the flesh. The body can be viewed by the naked eye, but flesh does not have this visibility. In formulating the dynamics of the body, Rivera says that “bodies enter into the constitution of the world….and social discourses divide the world and mark bodies differently” (Rivera, 2). She highlights that both gender and race significantly determine the way in which our bodies are affected by the construction of social norms. Rivera describes poetics as the linking source for human expression in illustrating the transformation of flesh into becoming the state of a body’s relation to the world.Historically, theological texts have illustrated the body of women in the nature of submission,while the male body in a dominant nature. Rivera implores that the body is natural, but influenced by sociocultural constructions and representations both biological and ideological. In monotheist religions, powerful figures such as the divine are generally depicted in the form of a male. She explains feminist theologian interest in deconstructing the relationship between divinity and materiality that depcits God in a masculine body.

Through Laura Padilla’s work in “Latinas and Religion: Subordination or State of Grace”, I gained an understanding of the history behind the way culture and religion are active in Latinx communities. I felt this reading gave me insights to the first posting I made about my interest in the influence of religion in the decision making and domestic life of Latinas. Padilla says that Latinas are socially conditioned to believe that they must accept suffering in a dignified manner, and they should not let others interfere in their problems. As previously established, Latina is a fluid term that can not entirely encompass a uniformed cultural representation for the inhabitants’ various countries. Therefore, I am not sure if we can assert this cultural statement by Padilla for all Latinas, and she does mention in the beginning that her essay reflects Latinas of Mexican American descent that she is most familiar with. Padilla says that this social conditioning leads Latinas to take unfavorable roles in domestic life as they were “preordained” for them. I can see how this social conditioning can cause woman like the ones on the “Femicide” clip to stay in domestic violence relationships or be frightened to seek for help earlier in their trouble. She also states that Latinas culturally share a high reverence for family, and also share an intimiate relationship with God. Padilla beautifully describes Latinas’ growing visibility in Church involvements, and elobrates how Laitna’s draw strength from communidad de fe. She sates that personal survival is intertwined with community, and implores that Latinas can redefine the Church as a safe place for social liberation and strength.

After this last week, I think that Padilla’s article on religion and Latinas gave me greater insight on how religion and the body are interconnected. As Padilla notes, “religion simultaneously subordinates Latinas while serving as a source of strength” (974). I especially like this statement since it reflects back on the concept of neplanta that we discussed last week; religion does not have to occupy a totally defined space in a Latina’s life. This especially comes into play later when Padilla points out how “Latinas [have a] cultural tendency to accept their fate of suffering with dignity” (975) alongside Latinas’ “reverence for family (977). Latinas are willing to work for their family, instilling in their children the very religious doctrine that willingly subordinates them. However, despite their faults, Latinas still seek family and religion as sources of strength during times of hardship. It’s a very interesting dichotomy: family and religion as both a pillar a strength and a source of contention. The lines become increasingly blurred as we consider strong women that are revered by the Catholic faith, like the Virgin of Guadalupe, who is a symbol of strength for many societal outsiders, like the natives during colonization, while also embodying an impossible standard for women.

I believe this all comes into play when we watched the video on feticide in Honduras. The cultural tendency to disregard Latinas has lead to a toxic societal tolerance in Hispanic cultures for women’s suffering. While religion does hold a special place in the lives of many Latinas, we can also not forget all the harm that is has caused many Latinas too.

This week, it was extremely interesting to include the body (or flesh) in Religion, as they are not commonly positively associated with one another. Rivera’s piece about the “poetics of flesh” was compelling, especially with its emphasis on flesh as a changing, ‘slippery’ concept. Rivera’s distinction of the body, which has a naturalized illusion of ‘wholeness’ and flesh, which represents the constant change of subjects and is marked by arrangements of power and social practices, offered a useful analytical category. I enjoyed the more vague, ambiguous term ‘flesh’ as it has the potential to incorporate a more immaterial (or at least less physical) representation of the body, as is a term that embraces change, something integral to studying the body discursively. The reading reminded me at multiple moments of Audre Lorde’s “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power”, especially in the author’s dealings with the dualism between mind and body in religion. It made me wonder how Lorde’s ‘erotic’ fits into a religious practice, as well as forced me to reflect on the many ways that the body and mind come together in the practice of religion, especially for women. Over quarantine, I read “The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao” by Junot Diaz, and in it, many female characters have long spells of praying and conversing with God that are as much physical as they are mental, and this reading made me go back to the novel and reflect on the author’s description of their flesh and bodies while praying.

Padilla’s “Latinas and Religion: Subordination or State of Grace?” was harder for me to get through, but once I got a grip of the language and style there were many questions I wanted to deal with. More than anything, I was fascinated by how the author painted a picture of religion and theology that had radical, subversive potential. It was challenging to conceptualize of religion as both a source of strength and a source of subordination for women, despite this duality being something I witnessed often as a child. More than anything, I found Padilla’s ‘tenets’ of liberation theology to be extremely fascinating, especially how the reform of institutions liberates not only the oppressed, but the oppressor as well. Does this mean that roles of being oppressed and being the oppressor are preordained? What does liberating the oppressor look like and how does it complicate liberation for oppressed people?

Reflecting upon the most recent topics and themes derived last week’s readings, I would identify key takeaways from our discussions that successfully contributed to my expanding knowledge in Latinas and Religion, and in the particular theme of last week being flesh. On Monday, one point of discussion I appreciated having as we transitioned into Mayra Rivera’s text, ‘flesh bodies’, I thought the class discussion on the opening of the text was important, “Flesh carries memories of theological passions. In Christianity, flesh evokes a creative touch, divine love, and suffering. More prominently, it alludes to sin, lust, and death. To be described as living “according to the flesh” as Jews, women, and sexual minorities have been being to be considered trapped in sinfulness” (1). Here, Rivera ties together certain connotations to flesh as well as meanings and symbolic associations. The topic of flesh, and especially its relationship to religion has previously not crossed my mind before, yet Rivera introduces the variety of connections to flesh that remains historically, culturally, and personally. Moreover, the idea of flesh versus the body was interesting to understand that there are complex qualities that convey the individuality of fresh, evolving relations, different interpretations, and discourses over the topic. Additionally, I thought the comparison to the body functioning was interesting as it was brought up with the mentioning of Theologian Sharon Betcher’s book, “This book seeks to unsettle the reifying tendencies of “the body” by evoking carnal interdependence, vulnerability, and exposure” (5). Overall, this week I can truly reflect on the interesting discussions on flesh and its relationship between the socio-cultural, historical, and personal components of our life and its theological evolution.

While reflecting back on Mayra Rivera’s piece, I think that her discussion at the beginning on the difference between flesh and body. She discusses flesh and body all throughout the piece but her description of flesh and body towards the beginning struck me the most. Rivera describes flesh as “formless and impermanent”, while the body is “an entity complete in itself and visible to those around it.” I understood it as flesh constantly changing without society noticing (could possibly be more metaphorical), while the body is on its own journey to change that’s a lot more visible to society. This could be right, this could be wrong, I’m not quite sure if I understood it correctly but I hope so.

When we talked about the body in class, we talked more about changes in body. For example, we talked about the subordinated woman being in her “natural” state. Her natural state being in poverty or including violence. I think that changes in the body would mean coming out of that idea that the body must be abused and continue to be abused as the natural state. Women’s bodies should be in unnatural states, always. Bodies in the unnatural state would allow for liberation (of the body), I hope.

Lastly, I think the idea of deconstruction has helped me come up with a new way to approach our readings. In class, we discussed how deconstruction means going to the root of a problem or reading perhaps and looking at what’s left of it in present times. Looking at what’s left and in our present circumstances with help us propose another solution or reading of the problem. When we’re discussing future topics, I want to approach my readings with the deconstruction idea.

Looking forward to this week’s discussion!

Prior to our readings this week, I had viewed the term flesh in the religious context as the exact opposite of purity. My experience with religious conversations about flesh and the body were very similar to those that Rivera describes, where it is strongly attached to sinfulness such as lust. Women were the main problems with this, although these things were more implied than spoken; messages to young women in the church was “save yourself for marriage and maintain your purity”, while men were instructed to flee and avoid sinful and seductive women. I have thought a lot about gender roles in Christianity, but I did not recognize some of these more subtle forms of enforcing subordination until after I read Rivera and Padilla. I had always known that the body was one of the primary ways to instill patriarchal ideals among Christians, but I had never explored ways of interpreting flesh.

One of the things that I liked about Rivera’s concept of the flesh as flexible and moving is something that connects with Padilla’s interpretation of religion as potentially empowering. By viewing the body as the more common Christian definition of flesh, which is entirely sinful and wrong, a person who chooses to abstain from sex until marriage has the same body and flesh the day before and after their wedding, so physiologically, nothing has changed. But I think that by interpreting the flesh as a changing entity, one can find it empowering or liberating to consider how their flesh and being has shifted as they transition to various stages of their lives.

Monday’s discussion revolving around contradicting gender labels and expectations, alongside Eric Barreto’s Reexamining Ethnicity: Latina/os, Race, and the Bible and the ABC story about femicide in Honduras all helped me better understand ‘the body’ of Latinas in religion. The double-edged implications that Latinas must live with, within a religious context, was first introduced to me in Monday’s discussion regarding the importance of a masculine God and the strong but feminine Virgin Mary. I knew about the implications that a masculine God had on societal viewpoints on gender but I had never thought about the role of the Virgin Mary and how her image has continually constructed and reinforced harmful cultural attitudes and practices around Latina womanhood. This is not because it never occurred to me but rather due to the fact that I wasn’t raised in a religious household. How the body of the Latina has had both forced and innate implications placed upon it was clarified when we talked about the desire of the virgin woman and the desire of a mother, but how the desire for both sets Latinas up to fail from birth. In relation to this, the largest point I took from Eric Barreto’s Reexamining Ethnicity: Latina/os, Race, and the Bible was the extreme clarity but simultaneous ambiguity of ethnicity and race in regard to Latinx folk and how both reinforce and originate from biblical scripture and understandings. The body of the Latina, therefore, is brought into a space even more ambiguous then what we explored in Monday’s discussion as her body not only reinforces and is sustained by gendered expectations but is also both defined yet undefined by the messy overlapping and clear distinctions between race and ethnicity. The ABC news story on femicide in Honduras, then, made me think about the disposability of the Latina body despite the theological importance the Latina has. More specifically, all together, it made me think about the everyday violences placed upon the Latina body brought upon by unrealistic gender expectations, which then become exacerbated when thinking about Honduran women of darker-skin tones as racial/ethnic violences are then allowed to enter her sphere.

In my opinion, Rivera’s and Padilla’s piece together provided a better understanding of ‘the body’ of Latinas in Religion. Flesh constitutes both a boundary and gate to freedom in the sense that it contains a negative connotation of sinful desires. For the Latina woman, flesh is this sign of purity that involves a nature of submission, This contributes to the idea of women being weak and vulnerable. In this sense, flesh is a boundary to the true freedom of independence. On the other hand, flesh may be a gate to freedom provided that the individual embraces its true potential. The third space of the Carribean helps us understand flesh better by providing us with a middle space where there is an entanglement between both body and flesh. Again, this contributes to a struggle for identity as mentioned before in class. iLe’s Triángulo represents these questions by illustrating the two distinct possibilities for flesh: obstacle or gateway to freedom. Within the music video, one can see an enraged woman allowing her body to serve as a gateway for freedom. These thoughts relate to subordination and grace. In this case, a state of grace is equal to a state of purity. This is specifically related to Latina’s subjectivity where a state of grace is a state of liberty. In the past, the Bible has played a role in recommending women’s subordination, especially to men. However, as demonstrated with Padilla’s piece, the Bible may be interpreted in a way which Latina women/women are actually empowered.

One of the main concepts that stood out for me after last week’s readings was the difference between “flesh” and “body that Mayra Rivera’s piece “Poetics of the Flesh” elaborated on. Before ever exploring this topic, I had the same definition for body and flesh since it’s what I was taught growing up in a Catholic environment. The word flesh’s interpretation/meaning is more malleable, and it can have various connotations, such as “lust, instinct, sinfulness and death” (Rivera, 10). Rivera also emphasizes that the word flesh is feminized after associations that derive from Christianity’s views on flesh, linking it with carnality and impureness. As Anna mentioned, this also reminds me of Lorde’s “The Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power,” which was focused on utilizing the erotic as a form of change and power. Since White-Western- Male-dominated hierarchies, including religion, have been implemented for various centuries, they have established patriarchal models in sexuality and education, promoting the idea of purity and virginity as well as opposing and considering immoral any woman who is outside of these categories or is not submissive to men. These ideas are also reflected in Latinx societies and communities, which can be seen on ABC News report on Femicide in Honduras. Femicides reinforce the idea that women are just bodies, and since they are objectified, these bodies can be disposable and easily replaced. The permeation of these ideas unfortunately promotes gender-based violence and tries to justify the objectification and violence towards women.

Padilla’s article, “Latinas and Religion: Subordination or State of Grace” stuck with me the most and really helped define ‘the body’ and the role the church plays in a Latina’s relationships. It changed my perspective on religion that I had been a part of for all of my childhood. Padilla goes through the ways that Christianity has been built to keep women as subordinates; by their limited roles in the church and their limited say over their bodies (according to the rules of the church – contraception, and abortions) for example. I had never noticed how much power a church-run by men had on my body: I couldn’t get birth control (not even with help with hormonal issues), I couldn’t have sex, I couldn’t get an abortion if I did happen to get pregnant. The church takes away the body and tries to fit it into an impossible-to-fit mold. The Virgin Mary sets unrealistic expectations of the female body, it should be pure and innocent, but also strong enough to endure suffering. Latinas have had to look to this religion for answers and hope and have had to shape their own self to begin to attempt to fit these roles. We see in the video about the Femicidio how women are being disproportionately violated and murdered and the image of women that the church helps to paint doesn’t help with these numbers.