There will be select opportunities to earn extra credit, limited to attending events related to the themes of the course. For example, events hosted by Emory’s Institute of African Studies, the Institute for Developing Nations, or the Interdisciplinary Workshop in Colonial and Post-Colonial Studies will count. To earn credit, write a response of 500 words or more discussing the event and how you would relate it to the course. Post this on our course site, under “Event reports.” If you are unsure if an event will count, ask me in advance. There will be no other ways to earn extra credit. Plan in advance if you anticipate wanting additional credit. The amount of credit awarded will depend on the response’s thoughtfulness, engagement with course themes, and quality of composition.

HIST 285 / AFS 270 | SPRING 2019

On Wednesday, I had the opportunity to visit the ‘Do or Die’ exhibition by Fahamu Pecou at the Emory Carlos Museum. Pecou’s collection can best be described as contemporary African Art, consisting of paintings, sketches, sculptures and a short film. My first impression of Pecou’s art is the boldness and avant-garde nature of the illustrations. Without a doubt the artworks contain traditional and mythological aspects of African culture, yet the characters in Pecou’s depiction wear contemporary clothing such as sport shoes and shorts. The rich and vibrant colors, strong muscular bodies and masculine poses of the artworks convey a sense of power and unrelenting will. It wasn’t until listening to Pecou’s short film, however, that I had further understanding of the ideologies and messages he attempts to convey.

At the core, Pecou’s work is an investigation of the social epidemic of young black men and violent crimes committed by the Police, relating to the quote ‘Black lives matter’. As stated by Pecou, Black men have long faced discrimination and social injustice throughout the course of history. The image of Black bodies especially, is often associated with fear, panic and despair. Pecou even go as far as saying that “Black men’s bodies have maintained a peculiar proximity to death.” Therefore, Pecou’s art attempts to battle this image and instill power and spirit into the Black body.

The exhibition is divided into three parts, each presenting a different form of artistic medium. Despite the difference in artistic mediums, similar characteristics can be seen from the characters portrayed. That is, the characters all appear to wear some sort of mask, seemingly composed of grain seeds painted in white. The mask, which covers the characters’ faces represent the central theme of ‘masquerade’. The ideology of the masks ties into ancient Egungun traditions of memorializing ancestors through masquerade. “An Egungun masquerade in Yorubaland represents the incarnate spirits of ancestors who return to the village to interact with the living.” (Pecou) This connection to mythological believes is further accentuated through Pecou’s self designed Egungun costume, which he refers to as “New World Egungun Costume”. The costume consists of a masked hoodie, sweat pants, athletic shoes and flying strips of fabric. In the center of the costume, some names are printed in bold black font, which are names of the boys that passed away from misfortunes. In doing so, Pecou commemorates the spirit of the boys, permanently locating them in his art. The conjunction of traditional amulets with contemporary clothing calls for a new way of thinking about Egungun traditions in the ‘New’ World.

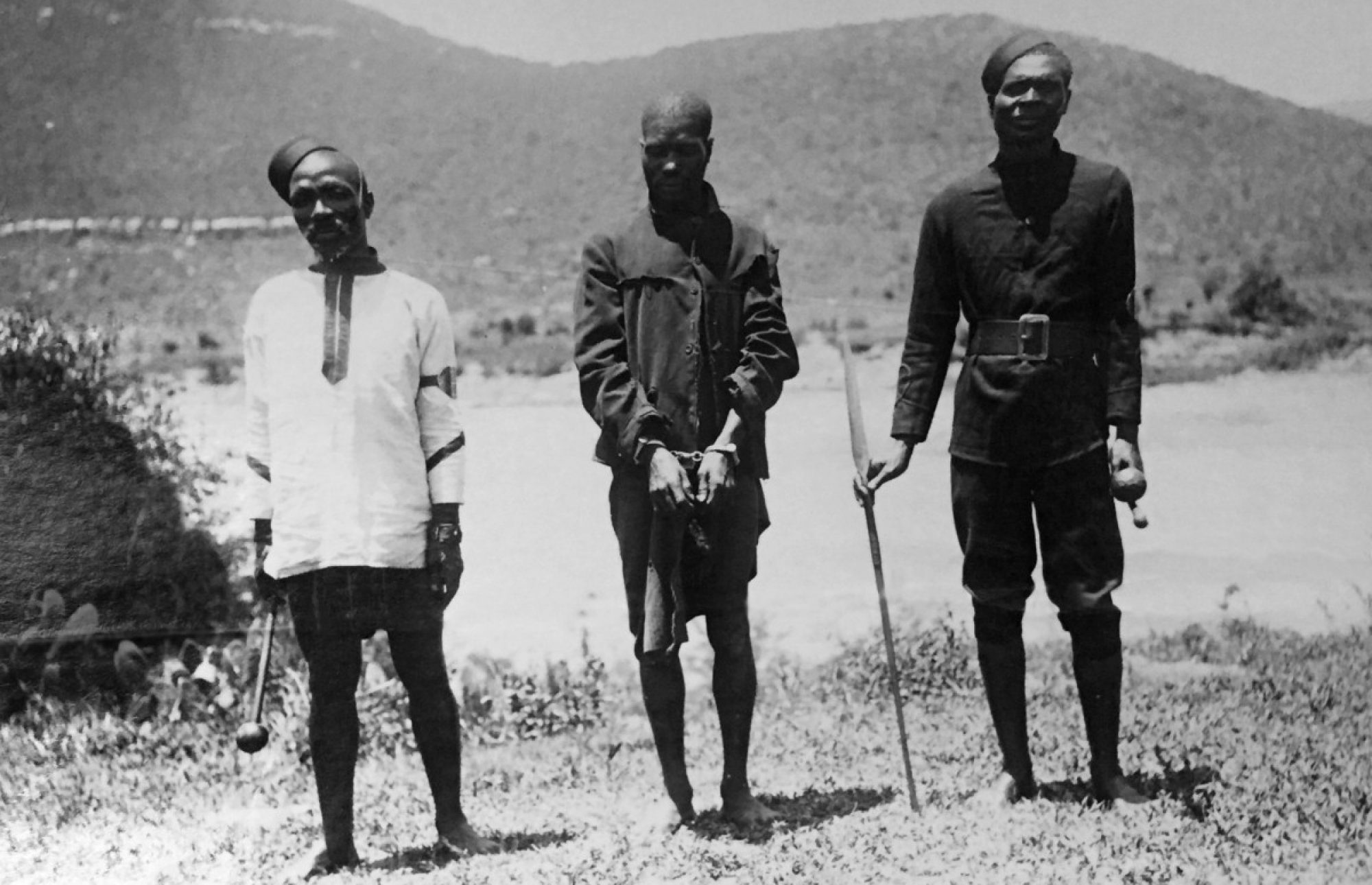

Relating to the class of ‘Law and Order in the Colony’, the works of Pecou remind me of the pictures taken under Colonial rule. The documentary pictures shown in class depict Black men as weak, depressed and unfortunate. Despite them being photographs, the pictures were taken with a purpose by western powers. The contrast between the power dynamics of White and Black men are vivid, clearly illustrating the social injustice that Black men had faced. Pecou’s art depicts the opposite, as presented by his character’s strong body and bold moves. Fast forward to our contemporary society today, social injustice undoubtedly still exists. Many young Black men have faced unjust trials and boys have lost their lives due to Police mishaps. Pecou’s works serve both as a commemoration of the young men that have lost their lives to social injustice, and a creative expression of Black power and spirituality.

I visited the art exhibit “DO or DIE: Affect, Ritual, Resistance” in the Carlos Museum. In this art exhibit, Dr. Fahamu Pecou depicts the connections between African traditions and the current violence against African American men with a specific reference to police brutality. The exhibit featured drawings, paintings, videos, music, and statues to illustrate the relationship between these two topics. The music and videos depicted more current examples of African American males experiences: police brutality and racially fueled negative stereotypes. Rap music played over videos of African American males being watched closely by police as they simply did regular, everyday things. The tension mounted as the video presented graphic images of law enforcement abusing and exploiting their power onto these young African American males. The paintings, drawings, and statues were extremely detailed. The drawings and statues typically depicted African men with traditional clothing, but this clothing had the names of African American men that are victims of police brutality. I think that this symbolized the juxtaposition between rich African traditions and the current persecution that African American men face. The beautiful, delicate, and ornate clothing is desecrated with the names of those that have unjustly lost their lives. The paintings typically portrayed African American men with tradition head-dressings, but the bottom half of their bodies adorned current clothing styles. This combination of clothing further illustrated the dichotomy of past and present African culture. I believe that all of this art is alluding to the concept that African history can no longer be studied without taking into account the suffering and mistreatment that African American men have dealt with. African cultures, traditions, and practices are now permanently entwined with the current hostility and prejudice African Americans experience.

I think that this art exhibit connects very well to a recurring topic in our class: the oppression and subjugation of African Americans in many societies. The history of many societies–and even present-day events in these societies–cannot be discussed without confronting this topic. Dr. Fahamu Pecou perfectly demonstrates this through his art exhibit. The beauty of African culture and traditions is belittled by the racism that African Americans face. In our class, we also discussed how colonizers or imperialistic powers tend to destroy and invalidate the practices of natives. This connects to how the importance and influence of African society are also widely neglected and rarely acknowledged. The background of an entire group of people has been ignored since society has labeled them as inferior and unworthy. As we have realized in this class, history is written by the “winners” and this tends to be the majority, powerful group. This group tends to be whites who have subordinated and marginalized Africans over time. The dominant lifestyle–or that of white people–has taken over and repressed the representation of minority cultures. African Americans have suffered endless persecution and hardship at the hands of law enforcement and governments that claim equality for all; however, this is clearly not the case. This art exhibit exemplified this, and I feel like it coincides with the general topics discussed in our class.

This past Tuesday, I was fortunate enough to visit the Carlos Museum, and see Fahamu Pecou’s exhibit entitled “Do or Die: Affect, Ritual, Resistance.” The core vessel around which Pecou centers his work is the black body: something that, in the United States, is both commodified and destroyed with impunity. Pecou’s work is startling. As a viewer of the exhibit, one is immediately struck by the sheer size of the his work: the exhibit begins with remarkably large paintings that nearly fill the walls of the relatively small space in which they are enclosed. The figures on these paintings, too, are incredibly large and lifelike. It is here, however, where context is needed to truly understand what Pecou is attempting to demonstrate and synthesize through his art. The exhibit — including the aforementioned set of paintings — is based off of the Yoruba tradition. The Yoruba are an ethnic group that principally reside in Nigeria. In his exhibit, Pecou seeks to synthesize and reconcile this culture with present-day American culture: a culture in which African Americans are systematically subjugated and murdered without consequence. The exhibit, then, fittingly begins with depictions of various divine figures. Pecou’s painting entitled OMIMYAMI, or “The Absolute and greatest,” displays this sort of godlike quality: on it are two women, and one white-masked individual, all dressed in white. They appear absolutely defiant: they stare down the viewer as if to challenge him, or inform him that their presence cannot and will not be denied in this space. This is an appropriate opening to the rest of Pecou’s exhibit, which as a whole, posits a distinct, clear thesis: that African American individuals can overcome the commodification and abuse of their bodies through the triumph of spirit — that ultimately, spirit and tradition in and of themselves constitute a form of profound and indisputable resistance.

As one continues to walk through the exhibit, they are confronted with more depictions of black bodies, whether they are in the form of paintings, charcoal drawings, or digitized videos. A persistent motif that appears regardless of the medium Pecou uses, however, is the white mask alluded to earlier: it is explained that this is the Egungun mask, a traditional feature of Yoruba societies. The mask is also an integral part of another motif that appears throughout the exhibit: “New World Egungun Costume.” This consists of a mask, numerous tasseled garments, and a piece of fabric that posits a list of various names. The list itself is reminiscent of a t-shirt design used often in the United States, but in this case, it lists the names of various unarmed young black who were murdered by police. In various images throughout the exhibit, these three motifs (i.e. the mask, the list of names, and the “costume”) appear and reappear in various contexts. What I believe Pecou is attempting to express through the utilization of these motifs — and by extension, through the melding of American and Yoruba culture — is that resistance to the subjugation and destruction of black bodies can be effectuated with the use of art. Through embracing the body and traditions that have been associated with it throughout history, the black body can be redeemed: indeed, it can be empowered in the face of oppression and systematic violence.

This exhibit offers a clear connection to the material we have studied in class throughout the semester. Particularly resonant here is our examination of Abina and the Important Men. Abina’s story is defined by her status as a wrongfully enslaved individual, and her active resistance to that status through the courts. While her efforts to achieve justice were ultimately unsuccessful, Abina is a quintessential example of the sort of resistance Pecou wants his viewers to embody in their own lives. Abina’s personhood was distinctly denied: she was made a slave arbitrarily, in spite of her objective status as a free person. Her body, then, was exploited and subjugated without her consent, just as black bodies throughout the United States are. I believe Pecou would posit that Abina represents the empowerment he seeks to evoke through his art — a sense of empowerment that draws on spiritual tradition to transcend the present, unjust moment.

Male Transients and Women Landowners in Kampala

On April 26th, 2019, I listened to Ben Twagira on his paper about Kampala. I saw numerous correlations with subjects discussed in colonial law and the Kampala city. Mr. Twagira alluded to the civilization being a monarchy before colonial intervention. The colonists forced the kingdom out and established a democratic-militaristic society. An interesting subject about housing “ownership” Mr. Twagira references is analogous to the western concept of squatter’s rights. When the king was exiled, partisans loyal to the crown followed the King away from Kampala. The departure of loyalists left vacated housing in the city center; which, women moved into. In Kampala, ownership is not solely defined by material ownership of that land but by the use of the land. The women made modifications to the property, which signaled the intent of ownership. This concept of ownership makes me think about the practice of colonialism. In class, we learned that foreign entities came to Africa and set up trading posts and invested in projects pertaining to infrastructure to aid in commerce. Although the colonist did not own the land, they showed the intent of ownership by pouring fiscal capital into the foreign country.

Mr. Twagira showed a picture of a door with a wooden latch to protect against intrusion. He focused on the modification to the property; however, I was more interested in the “owner’s” reasoning for such modifications. I understood the extra bolt as a form of protection from something outside. Colonialism began the process of instability and once the foreign occupiers left, there is a void of power that ultimately destabilizes the community. Fanon argues violence is the way to liberation. I do not know the history of Uganda, but I assume natives used violence to uproot the foreign invaders. I believe the violence that was necessary to rid foreign entities from the area lingered and manifested itself into domestic violent crimes. Thus, the wooden bolts are necessary, because of the lingering violence perpetuated by colonialism.

Mr. Twagira also writes about the women of Kampala. In Uganda culture, characteristics of independence and strength are associated with men. Women who “own” the houses are labeled as men, because of such traits associated with men. I find this odd. In Kenya, many of the men deemed affiliated to the Mau Mau were taken away from their villages and placed in concentration camps. The women had to become the head of the households and take charge of issues pertinent to the family. Therefore, gender norms were partially deconstructed due to necessity and not by choice. Back in Uganda, I believe the women’s strength and independence in the city center reveals adaptation without the patriarchy. Colonists encouraged the patriarchy institution and Kampala is a prime example of the reeling from that. Upon questioning about his labeling of women as men, he responded “these women misbehave like men.” I do not like his use of “misbehave.” I think he labeled it as misbehaving, because these women stray from the norm by being independent. It is not misbehaving but modernization. The identity of women is no longer constant but evolving, and I believe the women in Kampala are merely part of this universal trend.

This past Friday, I visited the ‘DO or DIE: Affect, Ritual, Resistance” exhibit located in the Carlos Museum. I was immediately struck by the cultural and personal import each painting carried – whether a quest for identity, or a struggle to reconcile the physical with the divine. The paintings – which depict the contours of racial resistance, ancestral spirits, and intergenerational healing – are bold platforms for uncomfortable truths. Before even entering the gallery, however, I read a dynamic exposé on African art, which explicated the soul and diversity of the paintings before me. Most markedly, the commentary expounded African art as a mechanism of “communion,” bridging personal identity, community entertainment, and the divine. Indeed, the mosaic of rich cultures nestled in the continent are implicitly woven into themes of identity, ancestral resurrection, and transitional elements between life and death.

One of the most powerful vehicles through which these themes were communicated was a short film depicting an act of police brutality. Beyond the physical act, however, the video unveiled the layers of struggle, spiritual energy, and healing that seek to be reconciled in our contemporary moment. As much as the video condemned the racialization of police tactics, it also reaffirmed the lives of young Black men. While the video is an artistic instrument of resistance against the state of police violence, then, it is also an animation of the invisible spirits who have a presence in our lives. The video, likewise, served as a common thread between the physical and the divine, with particular emphasis on the spiritual ancestors of African Americans who reaffirm the lives that were tragically lost. As much as the video despairs, it revives; as much as it depicts loss, it also depicts intergenerational restoration.

I believe this exhibit has far-reaching implications for our study of colonial states of resistance and formation. To this end, our intimate exploration of cultural strife and national identity in class tackles similar issues of racial hierarchies and subversion premised on cultural differences. Another analogous theme is that of mysticism, or emphasis on the spiritual in colonial contexts. Oftentimes our class discussions dissected broad intersections between religion or spirituality, ideas of rationality, and legal status in the colonies. The DO or DIE exhibit, like that of native customs of mysticism or narrative tradition, seeks to confront the hegemonic oppression engrained in societal institutions with a powerful resistant voice.

One point of further inquiry for me, however, is how native art forms constituted resistance to oppressive colonial structures of law and order. To this end, I think it would prove fruitful to perform an intimate analysis of native modes of art – whether narrative frameworks, or colorful exhibits of mysticism – in order to analyze how various artistic customs may have served as mechanisms of resistance in the colony. Furthermore, it would be interesting to perform a comparative analysis of native modes of artwork in the colony and the aesthetic forms of resistance portrayed in the DO or DIE exhibit. I believe we might see similar themes of identity formation, resurrection, and reconciliation between the physical and divine.

On April 26th, I went to Benjamin Twagira’s presentation of his fellowship paper “Male Transients and Women Landowners in Kampala”. Throughout the presentation, I saw how the course and this presentation were intertwined, especially with Mr. Twagira’s presentation of the situation in Kampala. While I did not have the paper beforehand, I was able to read through the paper during the presentation and see Kampala’s colonial status, and the repercussions this created, especially for women. Mr. Twagira opens with an explanation of the increased militarization of Kampala City, which was taken over by the British. Throughout the class, we have seen repeated British rule across time in our course, from South Africa to India, and repeatedly, they have used force in order to exact their will. Pre-colonial Kampala was allowed to maintain their kingdom despite the colonial rule, which is a major shift from the norm across colonial powers, but it also created a specific situation in Kampala that Mr. Twagira explored. One of the major themes that we discussed in our class was the role of women and in Mr. Twagira’s study, he focused on the role of women in Kampala and their capacity and indicators for ownership of property in Kampala City. He explored the fact that the only people who could own property are those who were not transient subjects of Kampala, which excluded much of the male population, but allowed the role of women to flourish in Kampala.

Mr. Twagira’s look at how ownership was characterised was an interesting look at the role of women. Using many of the same primary sources that we have seen and used in our own projects like documents and interviews, he worked on the ground in Kampala and analyzed the role of women to create his paper. Many indicators arose in his discussion, including how people maintained the modifications in houses to prove that they had stayed there, for example, the bars put on doors to keep out thieves or attackers. In his paper, Mr. Twagira discusses how women were the true residents of Kampala, as they were better positioned to present historically and could prove ownership through such modifications and continuous residence, while men were more likely to have a discontinuous residence in Kampala City. Throughout our class, we have seen the role of women and their role in African colonial society, from Abina to the women who wrote the songs that we read a few weeks ago. Often times, women are overlooked in their contributions and responses to colonial society. In his paper, I really enjoyed how he looked at the role of women and gave them agency when they are oftentimes overlooked by colonial studies. In our class, we have done similar tasks by giving agency back to overlooked groups and individuals like Kiamathi or Abina in order to preserve their legacies and review indigenous adaptations to colonialism. By abiding by the rules set in place, the women of Kampala City functioned within colonial society and created a space for themselves as owners of houses in the city.

Male Transients and Women Land Owners in Kampala, ca. 1930s-1996

Benjamin Twagira

On April 25th, I attended the seminar held by Benjamin Twagira. Mr. Twagira explains the interesting phenomenon regarding the big population of landowning women in Kampala. Contrary to other systems, ownership in Kampala is defined by the use of the land instead of material ownership. The first half of the twentieth century, saw the Buganda society underwent enormous transformations, particularly in regards to land tenure. In this context, wealthy and influential men owned multiple plot in different places. The ability of men traveling back and forth and staying only briefly in select places was a statement to their power and status. On the other hand, women used these homes to establish themselves. “The fact that the aunt was the one maintaining the plot, the one not traveling back and forth made it hers.” (14, Twagira) Therefore, a large population of landowning women emerged, shaping the Kampala neighborhood and its identity.

In response to Mr. Twagira’s dissertation, participants raised several questions. The first being the definition of ‘ownership’. A clarification of what ownership means is needed because there are restrictions to whom the tenant can rent or sell the property to. There might also be limitations regarding the use of the property, such as home remodeling. Therefore, whether the tenant actually ‘owns’ the property can be clarified.

A central theme of Twagira’s dissertation is the identity and role of women. Mr. Twagira presented a picture of a door barred with wooden latches in a resident’s home. The modification is an obvious means to prevent intrusion. At the same time, it raises concerns to the Kampala environment regarding instability, and the safety of women.

What I find particularly interesting is how ‘landowning’ women are perceived in Kampala. Mr. Twagira conducted interviews of elderly women who were the household heads. The women ‘expressed pride in their contributions to Kampala as a space, especially in their status as the real founders of the city.’ While the women seek to maintain their commitment to the cities, they were also referred to as ‘the widow or worse names’ back in their rural homes. At the same time, men who were unable to move back and forth between the cities and rural areas were derided as not masculine. This, as Mr. Twagira suggests, demonstrate the insecurities of Kampala men and women.

These gender norms in Urban Africa is a testament to Kampala breaking away from the patriarchy institution under colonial history. However, it leads me to question the effectiveness of such a system and the reasons behind such land ownership laws. Mr. Twagira writes: “If you had a plot and you were not using it, the government would take it even if you had paid for it.” In 1975, a law was passed for government to retake ‘unused’ plots in Kampala. How the ‘use’ of the plots is determined and the reasons for these policies lead me to think about the larger issues that exist for Kampala properties.

During this semester, I visited the “DO or DIE: Affect, Ritual, Resistance” art exhibition in the Michael C. Carlos Museum. This exhibition was a very exciting installment by Dr. Fahamu Pecou, which pushed me to look at the relationship of colonialism, African tradition, and the way that black bodies are seen and interacted with on a daily basis. Dr. Pecou used many different methods of explaining his point, pulling from photography, painting, sketches, and video to translate his message through different mediums. One way to connect this event with the course is by looking at the images of societal violence in the US today and the ways that we viewed this violence in our class. In class, we frequently talked about examples like the Belgian Congo or violence by old iterations of the police, who used violence on indigenous populations in order to maintain colonial control over these people. These iterations of political violence can be linked with the violence that is seen with African Americans in the US, just as Dr. Pecou pointed out. He used a series of three images to point out frequent iterations of when this violence was prevalent and to memorialize those who died during the civil rights movement, those who were lynched, and those who have been killed by police brutality. In our class, we frequently discuss this violence, and Dr. Pecou shows how this violence has functioned in a continuum throughout history and today, we still have to memorialize and provide a space for black bodies.

One of the other interesting aspects of this goes beyond the subject matter, but extends to the actual installations. Dr. Pecou’s use of the Ifá religion and the Egungun mask points to the deep ties to the Yoruba community in Nigeria, and despite the fact that many African Americans do not know their roots, those that do are extremely prideful. The space that community and religion offers is often a safe space from oppressive colonial powers, and preserves traditions through a means of resistance. We frequently speak about how resistance efforts were not just violent during the colonial era, and Dr. Pecou’s exhibition is a form of resistance, just nonviolent resistance. He is resisting the oppression and stigmas placed on black bodies in America, while also harking back to the same resistance that the Yoruba people maintained by continuing the Ifá religion, instead of taking on the religion of colonisers. I felt as if Dr. Pecou was inviting viewers into this form of resistance because specific parts of the installation, like the water, were interactive and could be touched, and viewers could also watch and experience the music video that he created. Art has always been a form of resistance and in Dr. Pecou’s exhibition, he does not just accept the constraints on typical forms of art and spirituality, but uses many different means in order to spread his message and resist how the continuities between how black bodies were treated in what we know as the colonial era through the present.

In our class, we talk about resistance, as previously mentioned, but the exhibition dives a bit deeper into some of the intersections between resistance, culture, and colonial identity. This exhibit plays very well within the themes of our course, from culture and conflict to resistance. We can see undertones and other forms of resistance, just as with the songs by the African women, and how art can relate to resistance in a more direct manner than traditionally understood. At its core, the relationship between black bodies and authority figures in the US is very reminiscent of the structures that we saw in our course with colonial powers, and Dr. Pecou’s exhibition points to this relationship and allows viewers to draw their own understandings of this conflict, while urging them to break the cycle that has continued over time.