Explain one way in which we can study Abina’s story through the lens of gender. How does doing so shape our understandings of colonial rule and its impact on societies such as those in the Gold Coast?

HIST 285 / AFS 270 | SPRING 2019

HIST 285 / AFS 270 | SPRING 2019

Explain one way in which we can study Abina’s story through the lens of gender. How does doing so shape our understandings of colonial rule and its impact on societies such as those in the Gold Coast?

Abina’s story is a clear example of gender inequality. Through reading Abina’s story, I think a key part of understanding her situation is recognizing that those in power were solely wealthy men. Whether these men be from Africa or from Britain, they were the ones that owned the land, had political power, and, ultimately, made the decision in Abina’s trial. These men are referred to throughout her story as “the important men”.

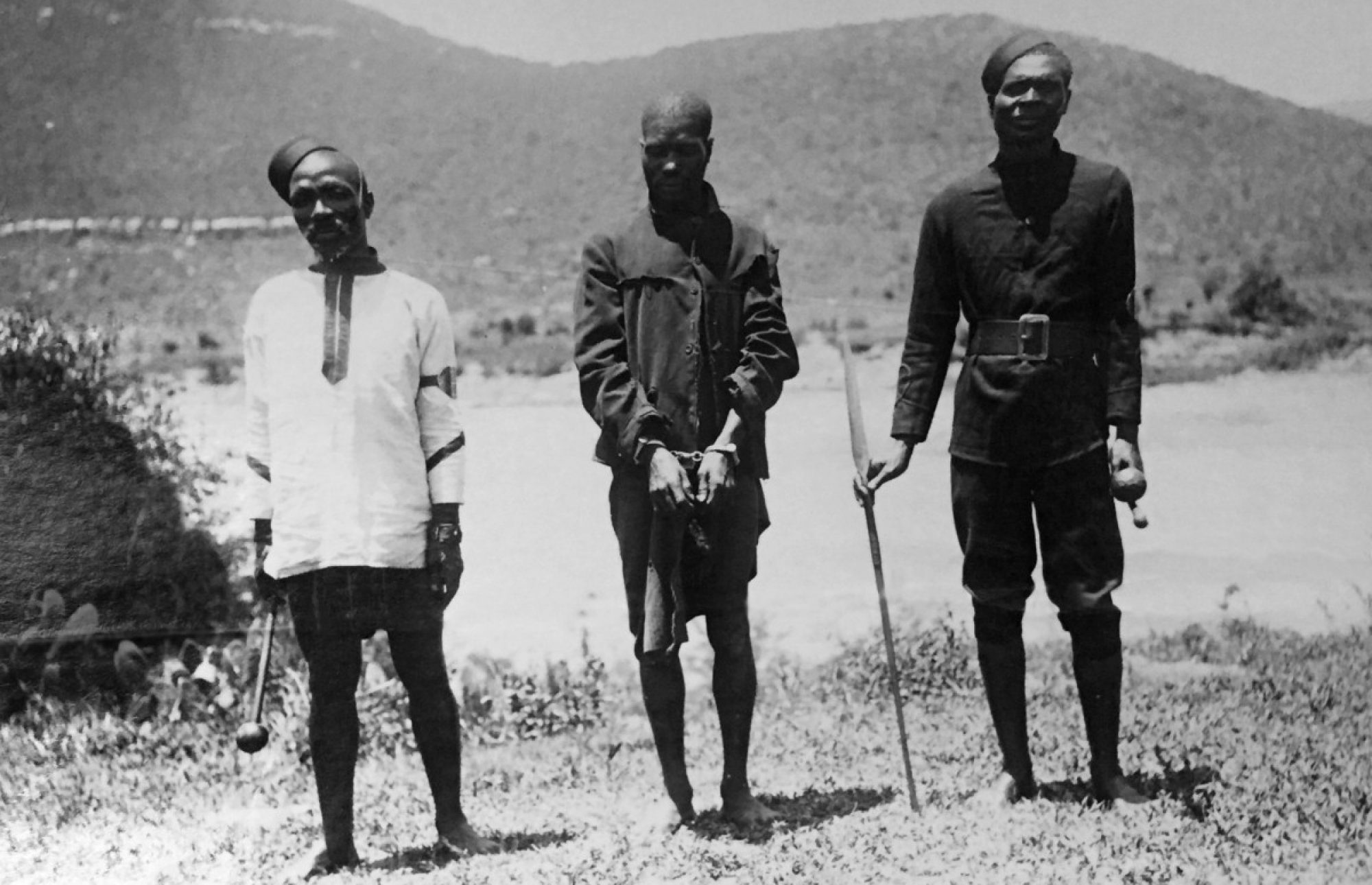

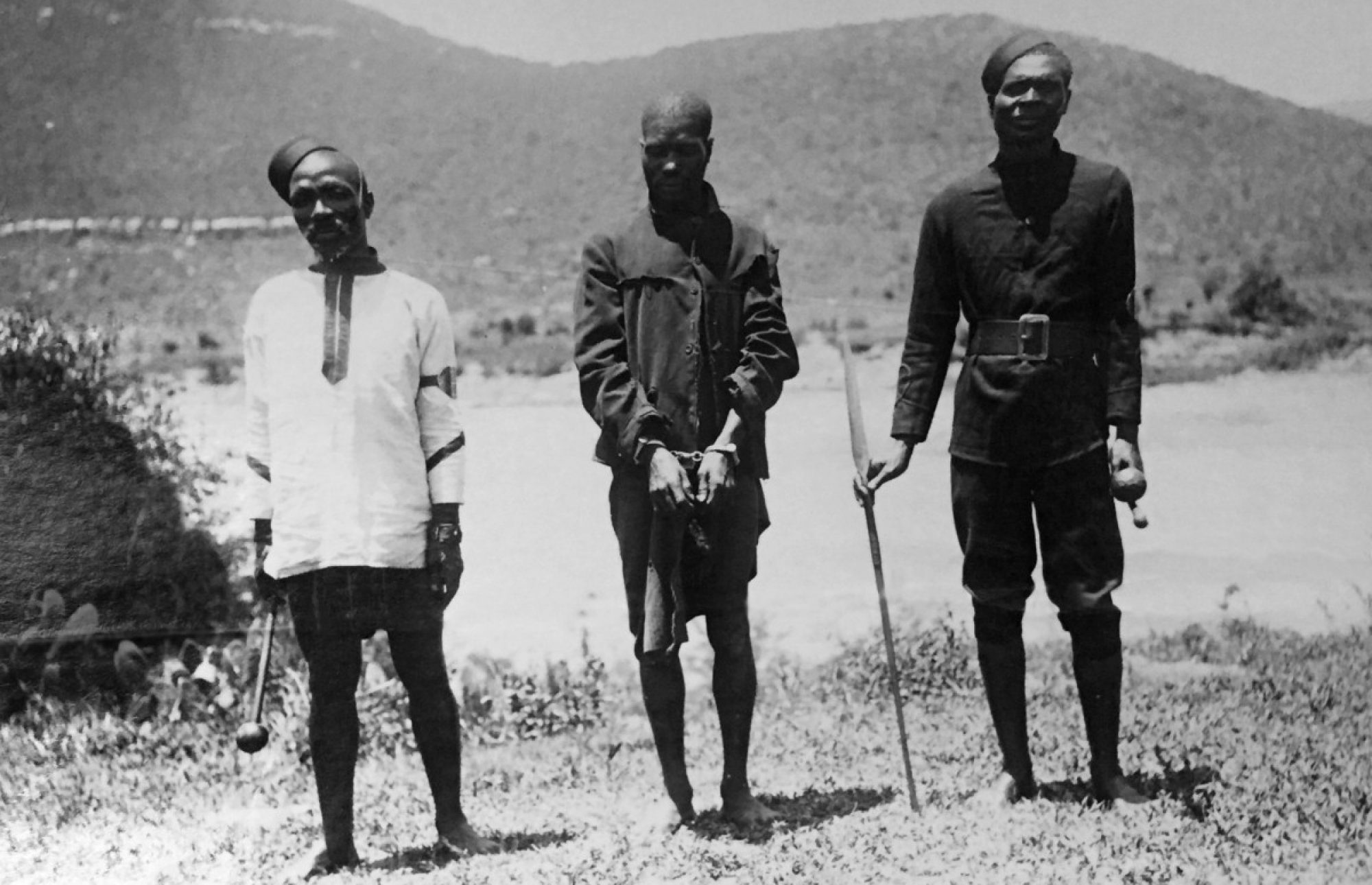

The clearest demonstration of a power inequality is when a jury is chosen to decide if Abina was being held as a slave. Her lawyer states, “To be a member of the jury, you must speak English well, you must own land or have money, and above all, you must be a man” (page 57). Through the British colonization of the Gold Coast, educated, land-owning, wealthy men rose in power drastically.

It is not surprising, however unfortunate it may be, that Abina’s case concluded the way it did. The British did not want to convict her powerful master; thus, angering those that are their main source of trade and profit. The men that presided over Abina’s case failed her. They did not see her claims as legitimate and were constantly demeaning in the way they spoke to her. The law is on the side of those that are most beneficial to the government, not those that need the help of the government the most.

Gender plays a significant role in the historical and economical development of Africa’s west coast. Captives were sequestered by gender: the men transported across the Atlantic while the women remained near the coast. Men were favored in the Americas, because men were deemed more able than women to deal with the harsh environment of the Americas. On the coast of Africa, women were desired due to the rich landowners’ ubiquitous conception women were less likely to run astray. In terms of the economy, more able bodies translated into capital and security wealth. Women possibly served as child bearers to their “masters”, which ultimately augmented the ruler’s power since family served as a form of governmental authority. Having a bigger family cemented the ruling figure–usually the father–with greater authority over the land possessed by that family.

Using gender, historians can fill in the information gaps of Abina’s case with historical references pertinent to that time. Around that time, it is known that young woman and children were desired as helpers; thus, Abina’s plea to the court that she was taken as a slave in her youth is credible since child kidnapping was a common practice during this time.

Due to British influences, government and male figures practiced behaviors analogous to paternalism. This means that male figures viewed themselves as father figures responsible for guiding others as a father would do to his children. This form of power legitimized by gender yielded greater disparity between men and women due to women having less of a say over their bodies and choices. In summation, Gender is an important proponent to Abina’s story, because of the many contextual layers gender reveals to this historical account.

Gender inequality is perpetuated through slavery, especially the power imbalances between white men and women of color. There are no women in power in Abina’s story. The landowners, politicians, and lawyers are all men, helping to explain the titular “important men”.

These “Important men” take complete control over Abina’s trial, taking away her agency over her situation. The jury is made entirely of landowning, English-speaking men. These men do not know what it is like to be enslaved, or be a woman, or even more, a woman of color, particularly in colonial times. They dismiss her arguments with a condescending attitude and diminish her experiences.

The perceived significance of a black woman in colonial times was based on her economic value. The government and political structures in place perpetuated gender inequality and segregated men and women. Men were sent across the Atlantic for labor and the women were kept near the coast and were kept docile and submissive. Women often bore their owner’s children who were born into born into slavery simply because of status.

This emphasis on male labor and female domesticity presses gender roles onto men and women who could not act otherwise and kept them as literal slaves to power-hungry white owners.

One pertinent set of assumptions in the transcript is a “whiggish construction” of the world that defined the context of Abina’s story, and colonial rule in Gold Coast societies, in 1876. Specifically, this whiggish reality was shared to different extents by “important men” such as Melton, Brew and Davis. The underlying assumption stands that law and order were represented by rational and oftentimes adult men who acted on behalf of those considered lesser, especially children, the disabled and women. Given that Abina operated in a world outside of the whiggish assumptions, the concept of her free will on the Gold Coast in the 19th century was insignificant and unrecognized. The idea of the whiggish construction, further, reflects the state of paternalism, or power imbalance positioning the status and agency of males over that of females, that accentuated the perplexity over Abina’s condition as slave or coerced wife.

Another set of assumptions is that the authors and illustrator of Abina’s story inject their own values of freedom, multicultural diversity, and gender equity that are distinct from those that existed in 19th-century West Africa. When applying this set of assumptions through the lens of gender, it is interesting to pose the reality of Abina outside the whiggish construction against the contemporary values of the author and illustrator. While the authors clearly sympathize with Abina, this empathetic sentiment in no way epitomized the feeling of the “important men” toward the experiences of enslaved women in the late-19th century Gold Coast. Thus, on the one hand, Abina serves as a lens through which to envision the behaviors and livelihood of enslaved women; yet, on the other hand, Abina’s specific experience is tainted with a contemporary and more hopeful interpretation. Furthermore, at risk when the modern value of gender equity shadows Abina’s story is a wishful interpretation of colonial rule and society in the Gold Coast.

An incredibly fascinating way in which we can study Abina’s story through the lens of gender is by examining the presence of colonial paternalism in the Gold Coast. This concept is explicitly defined in Abina and the Important Men: “ . . . [it is] the idea that men should organize and manage a society in the same way that fathers should play a leading role in their families” (168). It is no wonder that Melton declared that Abina’s claim was entirely null and void. Her various “owners” could logically not be considered as such: they were merely her protectors, providing for her as she attempted to navigate her way through the world as a weak and simple minded woman. Abina necessarily needed to be “under the authority of an adult male” in this gendered context (168). Thus, her relationships with both Yaw and Quamina Eddoo were justifiable to Melton, and others who shared the British belief in paternalism: if one was to consider the doctrine morally and legally legitimate, these men were merely acting in Abina’s best interest. She may have been under their control, but was not enslaved by them. Her lack of agency was not a marker of legal status, but instead a necessary and helpful social designation. Her womanhood, and ultimately her African heritage, were what made this so.

Engaging in this analysis is integral in shaping our understanding of colonial rule. In this specific context, European intellectualism was imposed upon the legal structures that individuals like Abina had to navigate as they attempted to secure their freedom. The gendered implications of this imposition are absolutely staggering. Nowhere in the native culture of the Gold Coast were conceptions of paternalism present. Indeed, matrilineal conceptions of status and familial relations were widely accepted: this would naturally negate the presence of paternalistic views in and of itself. Yet as Europeans infiltrated the region, their cultural conceptions became paramount in relation to legal and social institutions. In other words, two inherently incompatible conceptions of gender were becoming intimately intertwined. One necessarily rejected the other, and yet they existed simultaneously. How was Abina’s conception — one of matrilineage and agency — supposed to combat the one possessed by the judge presiding over her case? Ultimately, it could not. The legal, social, and intellectual ideas — specifically those relating to gender — of the colonizers won out. It is for that reason that voices like Abina’s were legally silenced.

In the reading guide section of Abina and the Important Men, the author mentions how Abina’s story is not just “hers,” but is morphed to also belong to those who retell it, rewrite it, or reimagine it– and then again to those who consume it.

While this is simply the nature of human memory and how we learn things, it is interesting to read an account of a woman who was dealt a great injustice by men, whether is be African men or colonial men, that is illustrated and retold by a man. Additionally, the court documents would have been transcribed by a man, and that is what we today have to go off of– the story of a woman as told by men.

This is representative of many stories of colonial Africa– those who are being acted upon rarely get a voice or the opportunity to tell their own story. This was especially true of women, who were especially vulnerable to forced marriage, enslavement, rape, and poverty; social conditions that make it near-impossible to form a lasting historical record that will faithfully tell their story.

Perhaps colonial rule not only sought to protect itself, but also African practices that were perpetuating the benefits of slavery and the blatant abuse of women– practices exacerbated by the entrance of European colonizers. The leniency on whoever and whatever kept colonial rule inline, whether it was actually abiding by the official English law or not, led to a colonial and post-colonial society in the Gold Coast that sought to maintain what “used to be”– slave labor, the perpetuation of violence against women, and corrupt justice systems, as this is what benefitted those few, minority, but ever influential “important men.”

Another way of understanding Abina’s story is to look at how her words were taken during court. During the colonial era and even after, women were not given the same social power as men. When it came to deciding matters in court, women were not, and are still not, believed as much as men are, especially black women. Abina’s story was never going to be successful in a court of law, despite the colonial laws stacked against her. She was fighting against the patriarchy, against colonial law, and against cultural law already present on the Gold Coast. In the comic book version of story, Abina was fighting against Quamina Eddoo, who has additional influence in the court as a male, but also her ex-husband, Yaw Awoah. The cultural rules in place during cultural rule placed serious importance on the beads and cloth that Yaw Awoah gave her, but in the colonial law, the two men could simply discount the beads and their importance to her. Abina was quickly shifted from man to man, with her agency stripped away from her by men. Abina’s role as a woman was diminished in cultural life, but also through colonial rule because even when she made clear that she was a slave and provided ample evidence, her word was not good enough. At each point of the trial, her life and trial under colonial rule were influenced by the men in her life, her lawyer, the jury trial, Melton, and even the transcriber. Abina was not able to have any sort of agency throughout the entire ordeal, preventing her from remaining her own person throughout the trial. The other lawyer is able to make her out to be a liar and undermined her credibility on the stand, changing how the jury came to their decision potentially. Gender undoubtedly shaped how Abina’s trial and story were relayed through history. By understanding her story through the lens of gender, it allows us to reconsider the impact that this lens may have had on the law. European societies imposed a rule of law on these countries that placed women at a significant gender imbalance across the colonial era, reshaping how these societies viewed women. Many times, women were on an equal level, if not revered in society, but with the introduction of colonial law, women were taken down and placed on a lower social status than men. The Gold Coast had its own rules and society before the appearance of the colonial rules described in Abina’s story. As we look at Abina’s story, gender is an impossible aspect to remove because it provides a valuable context to understanding the cultural distinctions that made the situation of Abina possible.

For me, the most compelling section of this week’s reading was its discussion about Abina’s status as a wife, rather than a slave (as well as where these statuses intersect and determine each other). As I was reading both the graphic history and the transcript, I specifically noticed that Abina repeatedly asserted that she was married to Yaw Awoah. In this aspect, it is clear that there were social benefits to being a married woman (which are more thoroughly discussed in the reading). I am interested in how this assertion interacts with her claim to enslavement. As a woman, she could be bought as a bride, and the purchase of a human being seems to be the biggest indicator of slavery to the British during this time. Thus, there is an amount of colonization occurring here: a traditional practice of marriage in the Akan culture coincides with the British definition of a process of a slavery.

Abina’s gender is implicit in every aspect of her story, even down to the title of the published graphic history, which clearly distinguishes that it is about Abina AND the important men, indicating that Abina is neither important nor a man. When it comes to determining whether she was a wife and whether she was a slave, it is important to remember that both came with cultural rights and definitions. She may have been either or both in her culture, but British culture dictated that though she may have been married according to Akan ritual, that she was not a slave. This strikes me as inconsistent, as it involves the rejection of one cultural practice but not another, though neither fell in line with British rites.

One very important way that we can study Abina’s story through the lens of gender is by taking into account the role of women in slavery. In the Gold Coast during the late seventeenth century, the demand for female slaves skyrocketed. This increase was due, in part, to the high rate of production of palm oil, which was seen as a woman’s task. Additionally, a woman’s ability to have children made her extremely valuable. They could dramatically increase the wealth of a slave owner by producing more workers to work on their land. These children could also be sold another slave owner at a very high price. Female slaves were also commonly forced into marriages with free men that benefit the man much more than the woman. Not only is it horrible that these women had no choice in who they would be connected to for life, but free men are not required to make payments to the family of their bride when she is a slave. In Abina’s case, she was sold by her husband and was being forced to marry another free man, Tando, as a transaction between him and her new owner, Quamina Eddoo. Her gender was a crucial aspect of her enslavement. It allowed her to be moved from owner to owner and married to whomever was beneficial to her master. She was not allowed any means of upward mobility besides escape. Her attempt to vindicate herself through legal means is especially commendable because of this reason. She could have simply stayed in hiding, but she chose to instead fight for the freedom of female slaves throughout the Gold Coast, which could have jeopardized her newfound freedom.

In my opinion by looking at Abina’s story through the lens of gender, one is better able to understand the sequence of events that led to Abina’s story. The mist notable image is undoubtedly the one residing on the cover of the text. Which depicts a lone female surrounded by men. This brings into question why is the sole female alone and being surrounded by males. Through the graphic novel we learn as to the reasoning behind why Abina needs a jury, but not necessarily why they must be men; as is such why it must be Abina who is the plaintiff. In contrast though, the book does mention how the jury can only be comprised of (essentially) those that are educated enough. During this time period, those that were educated were primarily men. The only women even capable of such a thing were the extremely wealthy. Thus, we are able to surmise the reasoning behind how the jury was comprised solely of men. Now, we could further analyze how it came to be that the society favored men in education, but to do so would go beyond the scope of Abina. Thus, we will now look at how it came ot be that the plaintiff is a female.

Without question Abina’s gender is pivotal to her story. For example, if she were male she would most likely of been shipped off to the Americas to work hard labor. Which would have in turned resulted in the impossibility of the sequence of events that was transcribed in the courtroom. Therefore, it is a reasonable explanation to say that Abina’s gender is one of the primary reasons we are able to even analyze this text at all. Furthermore, by being a female she also suffered the implicit discrimination not only based on her status as a slave, but also that which was inevitably associated with her gender, as somehow less than that of a male.

Using gender, we can supplement missing information about how gender worked under colonial rule. Getz states “…the question of Yowawah’s demand that she sleep with him to represent her conviction that man’s power over a woman’s body is a sign of his domination, and therefore, her slavery.” (182). This illustrates how gender can be used to uphold her status as a slave and how that in British imperialism, African women were sexually available, therefore African women are unable of being respectable. This idea of gender and power shapes the way that we see see the impact that colonial rule has on societies by adding another layer of subordination (as if they needed another one) to black people.

Gender has consistently played a significant role in Africa’s colonial and post-colonial history. Abina’s story is one that is of particular relevance to my understanding of gender dynamics in colonial Africa. Hers is representative of many stories of women in colonial Africa– those who have been portrayed in history as people being acted upon rather than important actors directly driving their own story. This is especially relevant to shape our understanding of one bi-product of colonial rule which is the silencing of women in African social spheres.

Prior to the advent of Europeans on the continent, African women not only had voices within their communities, but were also powerful and influencial leaders, as exemplified by the likes of Ghananian queen mother Yaa Asantweaa of the Ashanti Empire or Angolan Queen Nzinga. Cololonization however, had an unfortunate effect of transforming the gendered social fabric of many African societies, primarily by introducing European patriarchal principles and ideas, consequently making women become a social group that was especially vulnerable to forced marriage, enslavement, rape, and poverty – social conditions that make it difficult to allow women any voices or any historical record that will fairly and accurately tell their stories.

Gender is a dominant overtone throughout Abina’s story. At every turn, she is essentially the only female figure in her narrative—men physically own her, control her life and work, and ultimately decide her fate. The title itself, “Abina and the Important Men,” establishes the stark difference in status between Abina (with no descriptor before her name) and the men who influence her life, designated as “important.” British colonial philosophy is inherently patriarchal—the Crown is seen as a parental figure that serves to control and civilize the non-European colonies under their control, as a parent would control an unruly child. The transfer of British patriarchal structures—excluding women from any positions of power or authority—to colonies rewrites their cultural norms of gender. We see this extensively in Abina’s story, from Quaminaa Eddoo’s operation to the all-male jury that decides her fate, the imposition of British patriarchy controls the Abina’s (and all women in the Gold Coast colony) narrative.

Abina’s story of capture, bondage, escape, and silencing is not only capable of being seen through the lens of gender but, indeed, is required to be. Every step of her story was influenced by her standing as a woman in the Gold Coast—and a young one, at that. At the time of her capture, women and children were the most susceptible to slavery due to their inconspicuousness. With slavery technically outlawed, the easiest bodies to pass as “free” were women and children, as they were already considered subservient; the notion that women and children were the least likely to try to escape also drove the pattern of enslavement. Certainly, these factors came into play in Abina’s own capture.

Moreover, throughout the entire graphic novel, Abina is referred to not only as a woman but as girl: “She’s only a girl…” was the excuse used by Quamina Eddoo in his defense of keeping her under his “shelter”. Such statements only reinforced the notion that Abina would be unable to function independently of a man to take care of her and, essentially, enslave her—a notion even Abina’s counsel bought into. “A young girl like you can’t run her own life. The British are doing their best to civilie this place with the help of men like me. It isn’t civilized to let girls run around free doing whatever they want, is it?”

Still, the pervading idea of Abina’s perceived childish helplessness did not stop Quamina Eddoo from arguing that as a female, Abina was sold “as a wife”. Indeed, neither the jury nor the judge found such a statement odd, as doing so was a common practice at the time. Women could be sold as wives, as long as they were not being sold as slaves; the actual conditions of each state did not have to differ in any special way.

Finally, to be a member of the jury, one had to be “above all else… a man.” More importantly, you likely had to be an “important man” according to British standards. Not only did this setup doom Abina’s case, it can help us understand the impacts of colonial rule on the Gold Coast. In order to justify their own humanity, men in Africa had to distinguish themselves as “important”—owning land, wealth, power. They often did so on the backs of slaves, of children and, especially, women. The impact of colonial rule in this region was, among a host of other things, markedly a gendered one, reducing women from places of power to those of enslavement.

The theme of gender inequality is evident from the title of the graphic novel “Abina and the Important Men.” The author used intended bias to portray the incredible odds that’s stacked up against her, a young black woman trying to fight for her rights. Abina lived in a patriarchal society where men dominated every aspect of social life. Although Abina’s status is a wife on paper, she had no choice and was forced into marriage for the reason of slavery. In Abina’s case, a simple transaction between Tando and her new owner Quamina Eddoo. She was certainly not ‘free’, deprived of the ability of any social mobility. In her trial, not only were the judge and both defendants’ men, the jury completely consisted of men in power as well. “To be a member of the jury, you must speak English well, you must own land or have money, and above all, you must be a man.” (57) Not only was she fighting against the colonial and cultural laws, she is fighting against the patriarchy at the heart of the society. It is not surprising that the case ended as it did, with her agency being stripped away and was deemed a liar. The trial reshaped the fundamental values of how women were viewed by the society and gave an accurate perspective on the gender imbalance across the colonial lands in the era.

Though slavery involved men and women as captives, it was a predominantly male industry. Slavery was governed with a capitalistic mindset and involved the use of many strong men to do the rigorous labor. Through the perspective of Abina, we get an understanding of just how divided slavery became in terms of the different gender roles. Abina’s story begins with her being forced into captivity, even though slavery was abolished in the Gold Coast during this time. Abina is told that if she wants to stay in Britain without being placed behind bars, she must find a job. This is the first part of the graphic novel where the readers are exposed to one of the “important men” in the story. By focusing on Abina, we are able to read the unfair treatment towards women in an enlightening perspective and get an understanding of the power struggle that existed between the genders. Though some men, such as James Davis appear to be helping her, he is still forcing her to work as a maid for him. When Eddo returns and finds Abina, he forces her to return with him and sends her to prison. This not only shows the male hierarchical system in the Gold Coast during the time, it also gives us an understanding as to just how little power and say women of color had in terms of controlling their own lives, even after slavery was abolished. The men in this story failed to treat Abina as a woman and only saw her as an item they had full authority over. Though this is a graphic interpretation of Abina, this perspective essentially gives voice to a voiceless character in history. This is because anything written about Abina would have been from a male Eurocentric perspective. By placing the readers in the court room with a jury full of influential men in that society, we once again are able to see the dichotomy between the men and the women and the unjust, corrupt legal system that typically favored those who wrote the acts.

When examining the colonial laws and societal dynamics they perpetuated, or created, it is important to remember the societal differentiation between gender in the Gold Coast colonies. Specifically, Abina’s case is a legal matter that serves as an excellent keyhole to the nature of gender and its close relation with slavery in African colonial society. The case is argued against Abina on a basis that she was a wife not a slave, which shows a separation of citizenship in the Gold Coast colony of Cape Coast. In particular, Abina’s grievances with her purchase and treatment are argued as examples of her enslavement, but also as justifications for her freedom.

Once a keen eye is directed at the transcript of the case found in Abina and the Important Men, by Trevor Getz and Liz Clarke, it becomes apparent that the gendered treatment is similar enough to distinctions between freedom and slavery, which highlights the social dynamics between men and women in Gold Coast colonies. The distinctions between matrimony and servitude become blurred when closely examining the arguments of both side; this is shown in Adjuah N’Yamiwhah testimony when asked about the nature of the transaction for Abina saying, “[she was purchased] as a wife but he had her as a slave also when he purchased her he said she was his wife. Then he made her a slave, brought her to Salt Pond and sold her” (Abina 104). This account in today’s world would be a clear sign of foul play seeing as slavery, even at the time of Abina’s trial, was outlawed. That being said the cultural practices of matrimonial servitude and dowry payments for marriage make the lines between slave and companion blurred, an obstacle that Abina’s legal team needed to overcome. The moral high ground, legally speaking, becomes blurred after her “husbands” account of the original transaction is given saying, “I paid 1 oz gold for her to an elderly relative of mine named Fourie about 10 months ago” (110). This shows a complex dynamic of the post illegal slavery trade. Under the rouse of gendered channels of oppression that still remained, poor women like Abina became cornered into slavery under the façade of matrimony. This gender-based slave trade is something that can only exist in an inherently unequal society where citizenship is classed by gender now that freedom status is supposed to be unanimous. Therefore, understanding the Gold Coast illegal slave trade also serves to benefit our understanding of gender dynamics in the region during this time period.

In conclusion, the dynamics fostered through oppressive gendered laws, slavery and gender became linked in the post slave trade Gold Coast colonies. The knowledge gained from a reading of the Abina case through this lens shows the points of legal contention that arise when women are viewed as commodities that are bought and sold, despite slavery being illegal. Abina’s push back against the macro legal channels that oppressed her is an inspiring story about women who were willing to fight to bring about change, but also shows the uphill battle of inequality she faced in her post slave trade Gold Coast society.

An obvious gender element of Abina’s story is the fact that her court opponents seem to have tailored their arguments to appeal to British paternalism. Colonial officials like Melton come from a society where the father rules the family and has the power to discipline children, even physically, and to require labor of them. As a result, the slaveholders and near-slaveholders of the colony arranged (at least in terms of phrasing) their households in similar ways in order to avoid anti-slavery laws. When is someone who you make do chores, who cannot leave, cannot make decisions for themselves, is not paid and can be physically punished for not doing work when they are not a slave? At least in the colonial British mind, when they are a child. This also appears to be part of the reason why Gold Coast slaveholders preferred female slaves to male ones, because they fit into British preconceptions more. It is harder (though not impossible) to see Melton buying the same story regarding a male laborer.

On a different angle, it is also worth noting that what drove Abina to run away and seek her freedom was not that the work was hard, or that she had been logged, or that she heard of freedom in Cape Coast. The trigger for her escape was Eddoo’s attempt to marry her to someone else. This not only made her feel like a commodity (or breeding livestock), but also effectively declared her previous marriage to Yaw Awoa to be a sham (which it seems possible it was, though Abina didn’t realize it). It was this change in Abina’s understanding of her status that drove her to flee.