How do Thomas and Chanock characterize police power in the contexts they discuss? What factors do they say shaped police actions in relation to certain groups and activities?

HIST 285 / AFS 270 | SPRING 2019

HIST 285 / AFS 270 | SPRING 2019

How do Thomas and Chanock characterize police power in the contexts they discuss? What factors do they say shaped police actions in relation to certain groups and activities?

Thomas characterizes the police power as being necessary during “fundamental changes in authority” to prevent violence. However, he argues the police and the economic system are too heavily connected, with the imperial governments relying too heavily “on police services in all their major economic choices.” He says, “police power and legal sanction upheld coercive labor practices in the short term,” but argues that the exclusion of the native peoples in “key economic decisions” creates more problems and leaves the “colonial states vulnerable to mass opposition in the longer term.” He also talks about the colonial police forces in Sierra Leone and how their police force is heard “to the requirements of export production” and functions as a “defense of European commercial interest and the advancement of colonial administration.” Thomas is critical of this colonial police investment in the economic and commercial development of the location under their control and expresses concern about how it will undoubtedly lead to conflict.

Although he is talking about South Africa, Chanock is also critical of how “policing was increasingly concerned not with common-law crime, but statutory crimes peculiar to South African modes of control,” claiming their investment is also focused in economics particularly “the control of trade in gold and diamonds.” He does explain that the colonial police force does handle matters of broken laws and preventing violence, but that they avoid it more than they should, focusing on more economic control so the police are “not to be saddled with the day of the moral reclamation of the people.”

Neither of these authors claim that the colonial police forces should be removed completely, even recognizing their necessity in preventing revolts and violence from resistance, but both argue that the current system and investment in government and aspects of society beyond law and order will ultimately lead to conflict and create more problems than they solve.

Throughout history, the police has been used as a force for order-maintenance. Outside of America, the police have been used in a similar manner across time, even in South Africa. In Chanock, he explains the role of the police, as “the force on the frontier between coercive law and the people”. For Chanock, he explains how policing involves a permanent means of monitoring the people, both white and black. There is a difference in how white people were policed in South Africa and African Americans, but both groups were equally worried. Police actions in South Africa were concerned more with “statutory crimes”, than “common-law crime,” due to the group’s organization to monitor white crime, quell fears of Boer rebellions, and patrolling South Africa. In addition, the interest in monitoring alcohol and trading in gold and diamonds also shaped the police’s actions, by monitoring interracial relationships within South Africa.

Thomas approached the issue of the police with a more broad stroke, pulling in examples from around Europe during the colonial era. During the colonial era, the police functioned as a manner “to maintain order on plantations.” The police, just as in South Africa, did not apply equal force across the board. Often, “police applied symbolic violence to uphold the rules and hierarchies inherent to the imperial formation in which they operated,” which is a function that the police has taken frequently to maintain the institutions to maintain colonialism. Thomas explains how the police was used as a function for the larger state, and ultimately, in the chapter summaries, he explains how the economic development within Belgium, Sierra Leone, and Indochina have all functioned together to support plantation owners. Both readings have look at the police in different ways, but they both look at the connections between the police and social & economic control.

To begin, Thomas draws a connection between the “political economy” and the practices of the colonial police. White police officers were called in to oversee intersections between the economy and the government of the area. Specifically, Thomas states, “All colonial governments assigned police to help maintain order on the plantation, in processing plants, factories, mines, and other European-controlled workplaces” (Thomas 2012). The police used their repressive forces to push the “political economy” forward. To advance this agenda, imperialistic governments utilized police forces to take taxes and land from the colonies they controlled.

To further explain the presence of police forces and their power, Thomas relates them to the findings of sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Bourdieu developed explanations for the role of capital and symbolic violence in police actions. Thomas relates this to the decisions and behavior of colonial policing with, “Police applied symbolic violence to uphold the rules and hierarchies inherent to the imperial formation in which they operated … cultural presumptions and police actions were subject to the political order and economic organization” (Thomas 2012). Thomas creates the analogy of police officers being political actors and carrying out their force in ways that they believed upheld the norms and expectations of that location.

On the other hand, Martin focuses mainly on the policing in South Africa and its relationship to its evolving government. Martin states the police forces in South Africa were “overtly politicized” whose main role was “continuous and effective occupation” and “defense function dominated”. These police forces used the power to focus on statutory crimes over common-law crimes. Colonial policing here focused on enforcing these laws, Martin believes, to maintain control over important aspects of South African life: resources that provided political and economic wealth.

In continuation, Martin discusses the relationship between the aforementioned armed, political policing and the more minimal, ordinary policing. Martin draws this connection with, “It was not always easy to separate the aspects of ordinary and political policing in South Africa. The activities of the police were conducted against a backdrop of white racial panics” (Martin 2001). Although the political policing was meant to deal with the conservation of states resources and public order and the local policing was meant to deal with more normal crime, they both pushed the same governmental agenda. Martin is pushing the belief that police force in South Africa–regardless of what category it fell into–was used to maintain order and obtain resources while suppressing any chances of a revolt or rebellion.

Throughout history many have depicted police as those that are meant to protect. That police would uphold the law through and through. However, this is a problematic outlook. As many people often confuse legality and morality. Truly, it does depend on cultural relativism, which is why I will not attempt to analyze Chanock or Thomas in terms of good or evil. Only in terms of who the police were entrusted to protect. Chanock throughout his essay asserts that the police’s primary duty is to the government which created it. In contrast, Thomas believes the police to be one of balance, where they will protect either the people, or the government depending on which is in more need of stability.

Chanock argues that the police force centered in South Africa, is brought about through a series of government priorities, which also heavily influenced their attitudes towards different groups, as well as the type of laws prioritized. In Chanock’s article, he asserts that the “fears of both black and white revolt originally dominated the organization of its [South Africa’s] police.” (Chanock, 46). This quote states that the primary reason of the local governing force was to stifle and possible, present or future, revolts form either black or white citizens. While many people normally assert that it is police whose ultimate goal is to serve and protect (or at least a traditional Western idea of said police). In contradiction to the aforementioned belief, the South African’s police were originally designed to stop a future rebellion, and thus were designed to protect the government rather than the citizens. This was shaped due to the growing angst between those that were colonized and those that were the colonizers. In continuation though, as law is constantly evolving, so does the police force that upholds it. After tensions began to reside between both populations, the brunt of the police force fell upon left-sided politicians. Thus, began a period of a different, yet still similar in fashion, methodology of police. Where they were doing everything but what most would believe is their primary duty. Since the police’s attention was geared towards more political crimes that threatened the current political climate, more common laws such as thievery and assault were left mostly unchecked. I believe that this formulation of a politically motivated police force’s origin can be traced began ton those who first began it, i.e. colonizers. Therefore, it is with no surprise that the police uphold the controlling government and scrutinize those that dare to oppose it.

In contrast Thomas argues that the function of police is more artistic. That the police’s function is to “police different internal industrial disputes.” (Thomas, 2). This quote states that police’s purpose is to regulate any threats to the status quo, regardless of origin. Due to the significance and multitude of such a task, especially regarding large expansion of territories, it stands to reason that a culmination of a regulatory force, i.e. police, would be manufactured. Thus, the first factor resulting in police, according to Thomas, was the “sheer geographical extent and the consequent unevenness” due to the limited reach of the current police force. (Thomas, 2). This quote states that the police became more centralized as a result of the sheer magnitude of the governing area, as it would not be plausible for a small centralized force to have any hope of regulating everyone and everything; especially if the practices were different, resulting in complete chaos if left unchecked. The second factor Thomas proposes, is one of stability in essence. To clarify, within his essay he demonstrates the need for a foundational entity that is able to keep the current culture from imploding upon itself and the new culture, so that they may co-evolve. Of course, this is a nice way of saying forcing people being subjected by colonialism and ensuring they do not disrupt the process. The third factor was due to the relationship between the size of the economy and the repressive nature of the police. As a resultant of the relocation of traditionally field workers into industrialization resulted in a loss of traditional values, which naturally led to a progression of a lacking moral compass. Thus, a policing force was necessary to regulate a society that had just lost its moral compass.

Thomas primarily characterizes police power in the context of political economy, with coercive forces oftentimes attendant to industrial disputes such as organized strike actions by industrial workers. Thomas, likewise, illustrates how the colonial police force was intertwined with economic activity as police often collaborated with government labor inspectors to monitor the inflow of workers, their assignment to employers, and their eventual return home. More broadly, local economic structure influenced the nature of coercive practices in relation to the operation of colonial wage economies and the involvement of corporate and settler interests. The combination of metropolitan and multi-ethnic influences in colonial police officers, likewise, established a diverse legal framework – part European, part colonial and part customary – for the implementation of police power. Thomas, however, illuminates a primary caveat of repressive colonial police power: while police power and legal penalty maintained coercive labor practices in the short run, the denial of popular involvement in key economic choices ultimately rendered colonial states vulnerable to mass antagonism in the long run.

Chanock distinctly characterizes police force in the context of South Africa, and as a fusion of policing and defense functions. In early years of development, the police power emphasized its military dimension and was a meld of political and criminal elements, professional police and white public members. While the Police Act amalgamated the various influences into a single national force, inefficiency, poor education, and deficient legal instruction characterized the new bureaucratic power. Thus, a severe imbalance existed between the resources of the new State and the sophistication of the legal structure borrowed from imperial power over the years. Racial boundaries, likewise, stunted the ability of the black police to exert coercive power in order to police or arrest whites.

Chanock focuses on the cultural and ethnicity differences between the police and the state. More specifically, the police in Chanock’s context acted as effective occupants with disregard to common law. Much of the law enforcement was focused around the economy that benefited Europe. A key proponet of influence in the police force was racial distinctions. Chanock writes that the police was too constrained my unnecessary regulations centered on race: black officers could not arrest whites and black officers mostly patrolled black neighbors. Thus, racial factors and economic factors greatly shaped the militaristic policing that disregarded civil/common law. Another aspect is territorial and familial disputes. Literate black officers were desired, because they were the most “efficient” at policing the interests of the state. A certain tribe was therefore deemed the best for policing, however, since the composition of the police were prominently from one tribe, the police discriminated other tribes. Overall, the police served as an extension of imperial encroachment on the natives, because the police exhibited European sentiments and goals that conflicted native civilian purposes and needs.

Thomas scrutinizes labor coercion with colonial economic interests. Strong colonial economic ties yielded represses policing with interests analogous to the merchants and elites of the native community. A major factor is the use of violence as a symbolic form of suppression to uphold imperial institutions pertinent to that society. A major problem of the policing is the ambivalence to geographical locations. With locations comes cultures, and the police could not adapt nor accommodate the impenetrable cultures on such a tight budgets in that region. The police in this context served more as civil disrupters than civil upholders. In summation, Chanock and Thomas allude to ineffective and inefficient policing with disregards for common law. By common law I mean by the law of the civilian of that country. The police in both contexts promulgated racial and economic disparities in their respective societies. Therefore, this shows foreign intervention manifested in the form of native police.

In Chanock’s chapter on policing in South Africa, he characterizes the South African police force being overwhelmed in its efforts by colonial and racially oppressive structures. The white South African agenda dominated the police, whose actions were inextricably linked to the politics of the age. In fact, Chanock writes explicitly that “it was not always easy to separate the aspects of ordinary and political policing in South Africa” (Chanock 47). The South African police are characterized as acting almost as a forceful extension of the racist whites living there (both as civilians and in the government). For instance, they did not want black policemen both because they saw blacks as untrustworthy and because they did not want blacks to arrest whites. The police and their power were influenced dramatically by the political situation of South Africa, especially as it pertained to race. These situations were not exclusively on the white-black spectrum, as police power also changed with an influx of Asian immigrants. The police, in their interactions with interracial crime, preferred to convict a black scapegoat, and they were constantly working against the threat of rebellion.

Thomas’s discussion of police and government action in colonial states mentions that the ruling powers were especially sensitive to any growth in economic power held by the colonized. He also discusses how the police were meant to reduce the opportunity for protest. He writes that “government priorities and and the needs of key industries affected colonial police work over the course of the inter-war period” (Thomas 10). This statement echoes Chanock’s conclusions that the police were not there to perform ordinary police work as much as to extend the political goals of the colonizer. Thomas writes that “the most salient factor in state repression was local economic structure” (Thomas 5). He characterizes the police as being interwoven with various characters participating in the economy, both locally in the colony and abroad in the colonizing state. Both Thomas and Chanock portray colonial police as motivated by economic and political endeavors, as opposed to those dedicated to the welfare of civilians, as we might typically view the police.

Both Thomas and Chanock are similar in that they characterize the police and their power as political institutions, either to uphold the economy of the state or to exert their dominance. Conversely, Thomas explains, “the most common call on colonial security forces was not to defend the state against imminent overthrow. It was more prosaic: to police internal industrial disputes, whether organized strike actions by industrial workers or spontaneous work stoppages by plantation labourers,” demonstrating that colonial forces were closely tied to the “political economy.” Therefore, imperial governance was mostly absent. According to Thomas, strikes and revolts against imperial powers were the most substantial factor in the type of policing in the colonies. Chanock characterizes the police in South Africa purely as a powerful defense mechanism. Specifically, defending white people and their neighborhoods from black people. With the Police Act of 1912 and others, the British Parliament continually adjusted the policing efforts in South Africa to be more militarized and forceful.

In the context he discusses, Thomas characterizes police power as a function of economic interests, and political economy more broadly. The primary aim of his piece, he stated, was to “reveal . . . connections between police practice and the economic configuration of individual colonies” (Thomas 2). His broad argument, then, is that close examination of the economic status of various colonies will offer the best explanation for the contemporaneous actions of colonial police. To that end, Thomas is careful to note that many colonial governments had police forces stationed in individual plantation, factories, and so-called “European-controlled workplaces” (Thomas 5). The majority of the disputes they settled, then, did not have to do with much else apart from economic disagreements and confrontations. Repression, he notes, was often used as a mechanism to enact the economic will of colonizing forces. Yet it was also “self-defeating,” for once repression was used, it only ignited further outcry from colonial populations: it was not an effective coercive mechanism to achieve colonial economic goals (Thomas 6). Thomas also describes police work as being trans-national: it did not take on a distinctive colonial flavor depending on its geographic location. Policing functioned as an economic monolith, whose primary goal was to enact imperial goals. This was often done through the use of symbolic violence, as well.

In comparison, Chanock describes policing as it existed in the South African context, which was characterized by the ineffective mixing of policing and defense functions. The Police Act of 1912, “Created a single national force which was to . . . absorb . . . the local crime oriented police forces into a national force with a military character” (Chanock 49). An interesting aspect of this statute is its implications in racial relations. The aforementioned policing structure eventually became untenable, for the police force came to consist of generally undereducated white males, who knew nothing — if very little — about South African law and conceptions of justice. The choice to, for the most part, selectively employ only white males was unquestionably detrimental to both the black and European populations living in South Africa at the time. Black police were employed sparingly, which only added to the instability caused by the melding of policing and defense functions. The South African state, then, was scarcely able to police itself as a result of this policy.

The best way to discuss the approaches Thomas and Chanock take in their characterizations of police power is in the lens through which they view the actions of the police. For Thomas, that is through an economic lens, while for Chanock, the lens is a distinctly South African one.

Thomas explores the use of the police in European colonies (noting it was essentially identical in any and each European colony) and how the police were incorporated into the industrial system. They became so deeply incorporated that eventually the labor system was dependent on police presence as a form of labor coercion, creating an environment in which labor under colonial rule was necessary for survival as a native under colonial rule. While also enforcing policies and conditions within workplaces, police agencies also served as intermediaries of sorts to settle issues between employers and ’employees,’ and were deeply intertwined with colonial leanings and attitudes. Thomas claims that police violence in this sense became symbolic– the police protected the European colonizers by protecting their industries, and, therefore, damning the workplace, but less natural and human, rights of the colonized.

If Thomas took a macro glance at colonial policing, Chanock’s glance is somewhat more micro. Focusing specifically at South Africa and how the police and the military combined to form a new, different, and dangerous kind of policing. With the Police Act of 1912, the police and military forces were combined to form a power that was laden by the intricacies of race relations in South Africa. Because of the arbitrary rules that guided this new police-military power, the force was soon overrun with undertrained and corrupted officers. Chanock does, however, touch of the undeniable economic aspect of economics in South African policing, and how common law disputes were often ignored if it was in the interest of the European pocket book for the police force to involve itself in economic affairs instead, specifically the gold trade.

Both Thomas and Chanock view colonial police power as being expressed not for the benefit and protection of the people living within the colonies, but for the specific interests (especially economic interests) and desires of the Europeans in power.

In Thomas, this is a focus on police involvement in labor issues. All major colonial industries were labor-intensive, and the Europeans and wealthy natives overseeing these industries needed to keep a large, constant stream of labor available but also pacified. In Thomas’s view, this was done using the police as leverage (and sometimes a club) to swat down any trouble. While this generally worked well enough, Thomas believes that dependence on this force might have weakened the colonial hold in the long run. Using economic incentives and persuasive (rather than coercive) methods could have given the colonial laborer population a feeling of involvement and investment in the industries (and therefore the colonial system) that the use of police force did not. In such circumstances, the population would feel that it might actually lose something if the Europeans went home.

Chanock focused specifically on policing in colonial South Africa. South Africa was an extremely diverse colony (having not only numerous African citizens but the Dutch-descended Afrikaners, as well as outside immigrants from places like India), and the British used their police forces as the glue to hold the place together. South African colonial police spent a lot of time dealing with race-related laws and conflicts, as that was a constant potential flashpoint throughout the colony.

In neither author’s view were the police focused on establishing order and safety for the general population of the colony, especially indigenous populations. Rather, they were tools of power, more akin to an occupying army than a locally-grown domestic police force (even when many members were indigenous themselves).

According to Channock colonial policing was particularly about suppressing revolt or rebellion. He specifically discusses this concept in the South African context and identifies three main threats to British rule that guided the actions of police in this area. The first was the threat of rebellion from the African natives or as he quotes, “‘`dense masses of semi-civilised Bantu’”. Seeing as though the British have taken over their land, it’s important for them to keep the natives in an oppressed state to make sure that they continue to not believe that it’s possible to overtake the British occupation and reclaim their land. The second threat came from the white population. With this demographic, the police had to address crime, seeing as though there were gangs, and quell any signs of rebellion, especially in the rural areas. The last was the threat of a Boer rebellion. He quotes Milner and argues that these battle hardened men were, “ruined by the War, disappointed, defeated and even desperate”. He argues that a much more militarized force to patrol and weaken this population is the only way for the British to maintain control. His point of view is summarized in this quote, “The fears of both black and white revolt originally dominated South African policing and dictated the organisation of its police.” Thomas argues that the actions of colonial police were guided less by their desire to maintain order and more so by the desire to protect the economic interests of the occupying power. He states, “All colonial governments assigned police to help maintain order on the plantation, in processing plants, factories, mines, and other European-controlled workplaces”. He call this concept “political economy”, and goes on to talk about how it is directly connected to “labor coercion”.

Thomas’ characterization of police power is slightly less particular than Chanock’s. Taking a broader lens of simply British colonies as a whole, Thomas defines police power in terms of how it interacted with local populations—primarily, he argues, in an economic capacity: the “political economy offers the best guide to understanding what colonial police were called upon to do.” Essentially, with the colonial shift from localized agriculture towards waged labor came the need to police the economy, underlying the notion that colonies were, above all else, financial assets to the colonizers. Such policing took place in the form of quelling strikes and dissent and was largely directed towards local populations.

Thomas also points out that the makeup of the police force was quite diverse, drawing from the white population as well as the local population, and that while the broader police force was primarily concerned with regulating the economy of the colonies, their actual policing practices and punishments took on a more localized tone. Colonial police adopted local customs depending on the areas in which they were stationed.

Chanock, on the other hand, hones in to a far more specific view of the police force in South Africa. Noting that fears of revolt from both black people and uneducated, rebellious white people first drove the development of the South African police force, Chanock argues the police’s main task was the quell rebellion. In this, Thomas and Chanock echo one another. Chanock also discusses the Police Act, which merged the defensive aspect of colonial security with the more militaristic one. The result was a rather ineffective national force, semi-militaristic and exclusively made of uneducated white men.

Such a composition was problematic on multiple fronts. For one, the language barrier between the white police and the local populations stifled any effective investigation into disruptions. Moreover, a predominantly black population’s word against a white police force held no merit in a colonial society ruled by wealthy white men. Naturally, this police force was a semi-militaristic one, intent not on aiding the people but on maintaining public order through the quelling of riots.

Policing in South African colonies was primarily directed in “zones of interracial activity” and held, as Thomas argues, a distinctly economic role. The police force was concerned with upholding prohibition and stopping any illicit trade in gold or diamonds.

Both accounts reinforce the idea of the colony as a financial asset and economic pursuit, with policing intended to harness full economic potential from the colonies via policed control of the local populations.

Both Chanock and Thomas describe police intervention as something necessary for the well-being of the colonial states. They both describe this to be beneficial for the European powers, rather than the citizens. Chanock states that the police is typically referred to as ‘The Law,’ which is “an indication of their prominence in the characterization of a legal system as far as the public are concerned. ” Though this is said, Chanock explains how “that would not only terrorise the inhabitants but would give a great shock to the credit of this country throughout the world.” As we can see, the power that the police held was very influential over the citizens and did it to keep them in order through the eyes of the colonizers. Thomas, similarly states that “colonial policing has figured largest in histories of existential threats to colonial regimes.” This also gives us an insight as to how colonizers used police force to secure their power and control over their colonies.

Chanock also explains that though the police were used to reinforce the laws that were broken, they were mainly there to maintain the economic growth for the European powers.

Though these police powers seem so influential, both Chanock and Thomas make connections and distinctions as to how the police was there for both social and economic reasons. Additionally, as these police forces were brought down from colonial regimes and forced to maintain order in the colonies, they failed to fit the cultural and local standards.

Thomas and Chanock characterise police power as being immensely flawed as they suggest that police power exists mainly for the preservation of european/colonial power rather than for the safety/benefit of the general population. Thomas takes a critical look at police power as he talks about how systematically flawed police systems are. Although he advocates for their necessity in maintaining peace/preventing violence, Thomas criticises how the “police applied symbolic violence to uphold the rules and hierarchies inherent to the imperial formation in which they operated,” thus working to sustain colonial power and values. Thomas talks about the too-heavy link between police power and governmental/economic system by means of one existing really to serve the other rather than for the protection of citizens. Thomas talks about the potential threat the police offered the labor-intensive colonial system (i.e. using police to prevent any form of revolt/trouble). From an economics perspective, it is easy to see why Thomas contends this is why this didn’t work in the long run as offering people incentive/actually treating them decently would have kept them more satisfied in the long run. Chance largely asserts that the primary purpose of police power in South Africa was to prevent any semblance of revolt/revolution. Chanock talks about the distribution of concern the police force had in South Africa and it is apparent that their primary concern was economic sustenance/power control over general welfare. Both readings draw out fundamental issues that linger in political contexts across the world to this day. There should be no alternate agenda when it comes to welfare, and government systems such as the police force should not be used as a tool to help sustain power.

When examining police and law enforcement it is crucial to keep in mind that there can be no law without some level of external coercion on the populous. Looking at the situation in South Africa specifically, Martin Chanock speaks to the vital role law enforcement has in maintaining law and order in a functioning society and, in this case, how enforcement can be counterproductive if mishandled. The thesis of his argument hinges on the fact that there was no law nor order in South Africa, but the policing practices adopted were not a logical step forward and only served to increase the extreme tensions plaguing the society.

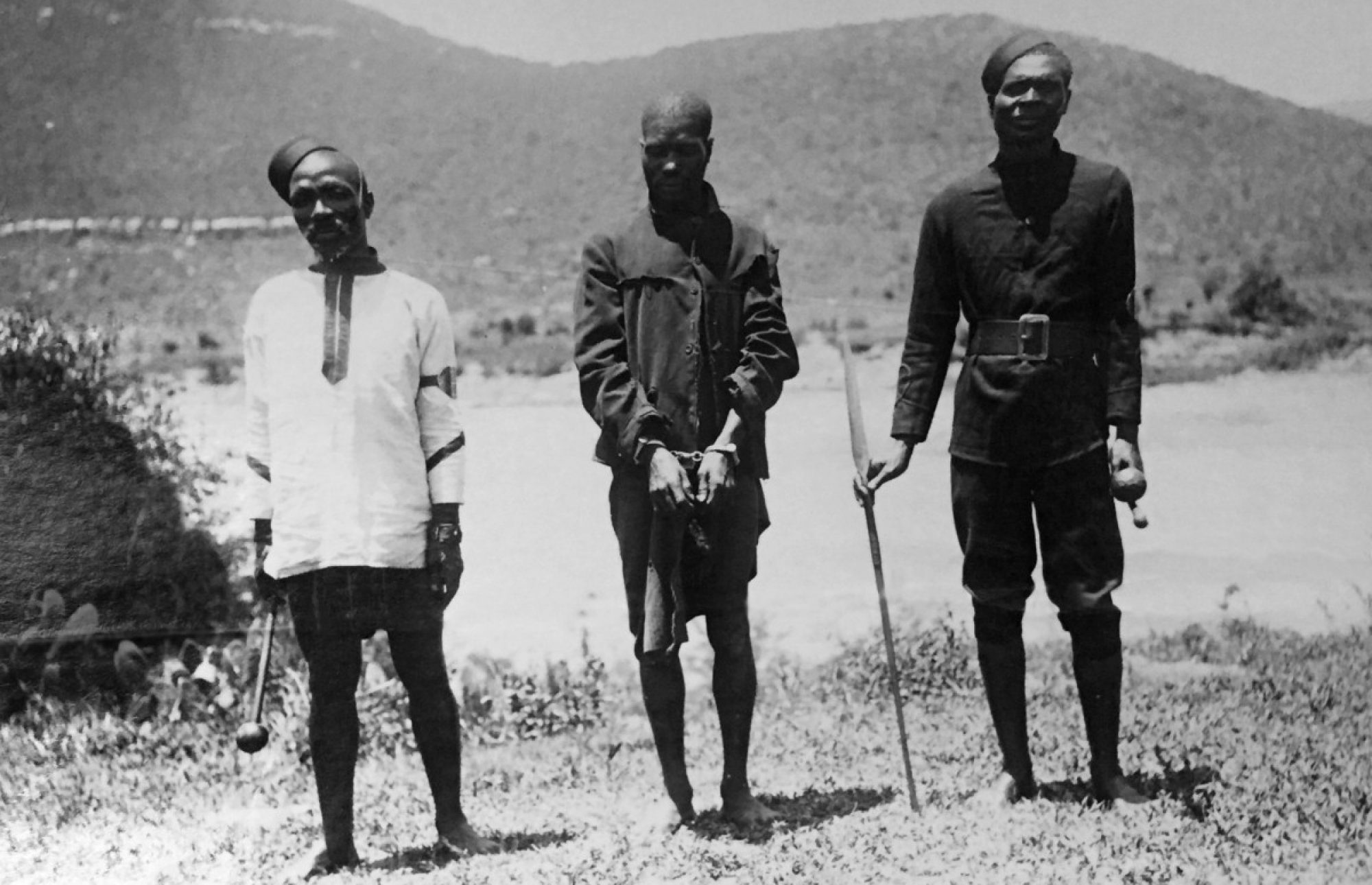

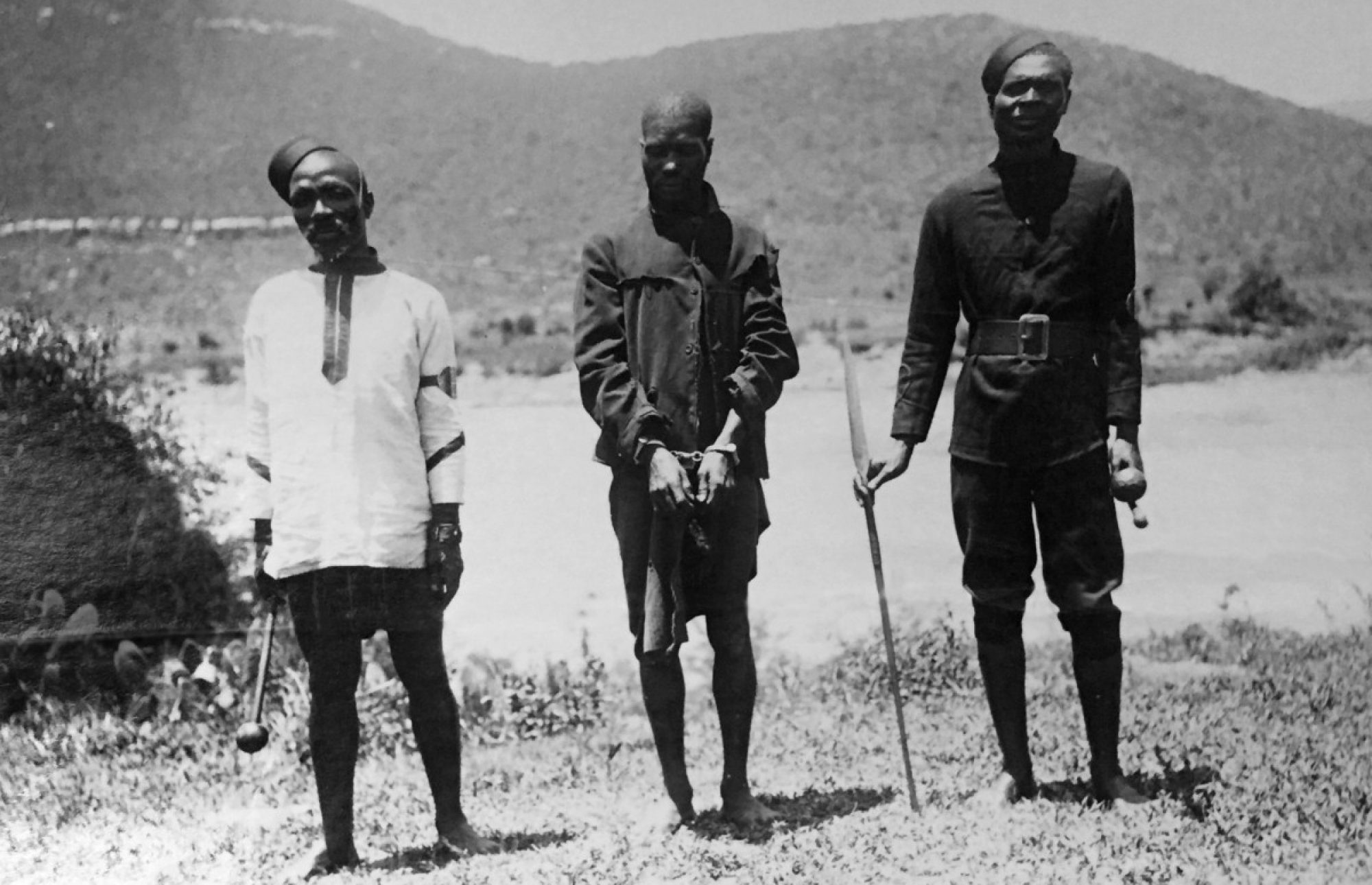

In South Africa, in response to growing social unrest, enacted a dual police force; one branch was tasked with maintaining regular policing duties and the other was a military trained suppression force. Although such dramatic action can be justified in a situation of unbiased implementation, in South Africa’s case the militarized wing of law enforcement acted more along the lines of a labor enforcement extension as opposed to actually maintaining law and order. Chanock speaks to how little they helped with actual crime writing, “withdrawal of rural mounted police once the war began was not an outbreak of criminal violence, but problems with the enforcement of labour discipline, and this underlines the crucial part that rural policing played in this.” (Chanock 57). The ethos behind the militarized policing agent was in response to the growing social unrest, yet the adoption and implementation of the mounted regiment served little in the enforcement of laws and furthered the cementation of the racially mislead status quo. The misgivings of the force can be seen in the vacuum of rural enforcement found during the war. When the force was removed crime did not rise dramatically, showing a logical disconnect in their methods of enforcement. With the historical aid of hindsight, it can clearly be seen that this sector of police in South Africa did not do what has and always will be the main priority of any law enforcement, to maintain order. In the mislead and racially charged implementation of laws combined with the obvious priority of the force being one of suppression as opposed to peacekeeping, the militarized police force was an example of a counterproductive method of enforcement that only served to widen the divide growing in South Africa.

Throughout history, the police have been used as a unit that is empowered by a State to enforce the law in order to protect people from crime and civil disorder. The police force is ideally expected to uphold the law they are bound by. In the Chanock reading, he focuses mainly on the policing in South Africa and its relationship to its changing government. Chanock makes it clear that the police forces in South Africa were “overtly politicized” as police actions in South Africa were seemingly more concerned with statutory crimes, than common-law crime. The South African police were seen as acting almost as a complement to racism within the government. For instance, they did not want Black policemen both because they saw blacks as untrustworthy and because they did not want blacks to arrest whites. Chanock also comments on how Black officers could not arrest whites and Black officers most often only patrolled Black neighbourhoods.

Thomas primarily characterizes police power in the context of political economy, and illustrates how the colonial police force was intertwined with economic activity as police often collaborated with government labour inspectors to oversee the arrival of workers and their duties to employers. Local economic structures seemed to influence the nature of intimidating practices of the police. Thomas also discusses how the police were meant to reduce the opportunity for protest.

How do Thomas and Chanock characterize police power in the contexts they discuss? What factors do they say shaped police actions in relation to certain groups and activities?

Thomas in his work seeks to interpret colonial policing through an economic framework. In the first part of the book, Thomas conducts a theoretical analysis of colonial order and policies. More specifically, he describes the relationship between the economic structure of the colonies with the politics of imperial oppression, alerting the reader on the different cultural backgrounds and local requirements. In the second part of the book, Thomas conducts a broad study on different parts of Africa, South Asia and the British Caribbean, citing examples of labour control in French, British empires within the years of depression. By doing so, the case studies connects the colonial wage and conditions with the economy of the state.

Chanock on the other hand, specifically mentions the police power in the context of South Africa. Chanock notes that because of the cultural and ethnicity differences between the police and the state, there were backlash on the colonial efforts. “Alongside the weakness of the state’s police, both the state and the large employers of labour developed their own systems of private policing of compounds and plantations.” (Chanock) More importantly, he states that the police work is more than just simply maintain order in the colonial society. It is more so to push forward the governmental agenda, in resonance with Thomas’ context of political economy.

While a police force is ostensibly tasked with maintaining safety in society, state power to influence individuals’ actions often leads leads to police being a threat to public safety. This was the case in apartheid South Africa, as Chanock describes in the chapter “Police and policing. ” Policing in South Africa had a dual purpose: enforcing laws in communities, and being a means of political control. Militarized police were used to prevent uprisings from Boer, black, left-wing movements, while local officers exerted control through “statutory” crimes such as mandatory passes and “masters and servants” laws. Chanock writes that South African law enforcement was “conducted against a backdrop of white racial panics” in response to ethnic diversity and subjugation in the settler-colonial nation. Racial tensions mired all aspects of law enforcement; black police were not permitted to arrest whites and often faced a language barrier to African communities, so local, community based policing was replaced with oppressive control.

Thomas takes a comparative approach in his writing, detailing the police systems of various European powers and global colonies. He examines the relationship between labor and policing in when colonizers extracted natural resources from the regions under their control. He writes of the common theme of class division among these societies, and that “police forces were tightly harnessed to state efforts to impose social control once the society in question became demarcated between dominant and subordinate groups welded together under a single administrative authority.”