What image of the British justice system in Kenya does The Trial of Dedan Kimathi offer? Discuss the techniques Ngũgĩ and Mũgo use to convey this image.

HIST 285 / AFS 270 | SPRING 2019

HIST 285 / AFS 270 | SPRING 2019

What image of the British justice system in Kenya does The Trial of Dedan Kimathi offer? Discuss the techniques Ngũgĩ and Mũgo use to convey this image.

The trial depicted in the reading of the Trial of Dedan Kimathi, is one that envelops the justice system in that of a subjective nature. While the most common and widely agreed upon definition of justice, is one that is unbiased, in accordance to the phrase “justice is blind.” Although, this trial is anything but, as there is a plethora of viewpoints that each see the justice system in a way that is completely unfair. For the white settlers, the justice system is too lenient, and enables the Mau Mau movement to wreak havoc among innocent people. Where another viewpoint from the perspective of Dedan Kimathi casts shadow of doubts upon a legal system that is biased and unwilling to hold fair in its own vision.

First, by looking at the white settlers, the authors introduce the settlers as devoid of sympathy for the indigenous people of Kenya, rather focusing solely on their own situations and lamenting for better days. They all remain completely oblivious to the obvious fact that in fact they are continuing a cycle that they blame for their own misfortune. Specifically, by looking at the angry white settler (who is later named as Dick), who grieves for the loss of his wife, daughter, sheep, and land. He claims that he is the victim of an oppressive system, that was unfair towards a simple soldier, forcing him under their own dominion (them being the colonial office, banks, and mortgages). Without irony this is all claimed to be reasoning that he has suffered, and thus demands justice to be served towards the bandits that supposedly are the party responsible for his losses; obviously this bears resemblance to the indigenous people of Kenya. Where the peaceful people of Kenya were oppressed by an unfair system and were unjustly treated and merely trying to make ends meet, are now demonized in the faces of people who have been subjected to the exact system they continue on another populace.

This brings us to another viewpoint of the justice system, which in addition to the one mentioned above also views it as erroneous. Although, this viewpoint contradicts the one that is too lenient (in accordance of the views of the settlers) and is rather too harsh. Specifically, this viewpoint can be seen directly from the words spoken by Kimathi, where he asserts that the system in place has its basis in lies. That it is completely unjustified in of itself to do what its sole purpose is: to provide justice. To clarify, Kimathi us asserting that the in-place justice system is claiming that the ends justify the means. This we can synthesize form the judges assertation that a society requires a justice system, as he eloquently avoids the claims of its unjustified founding.

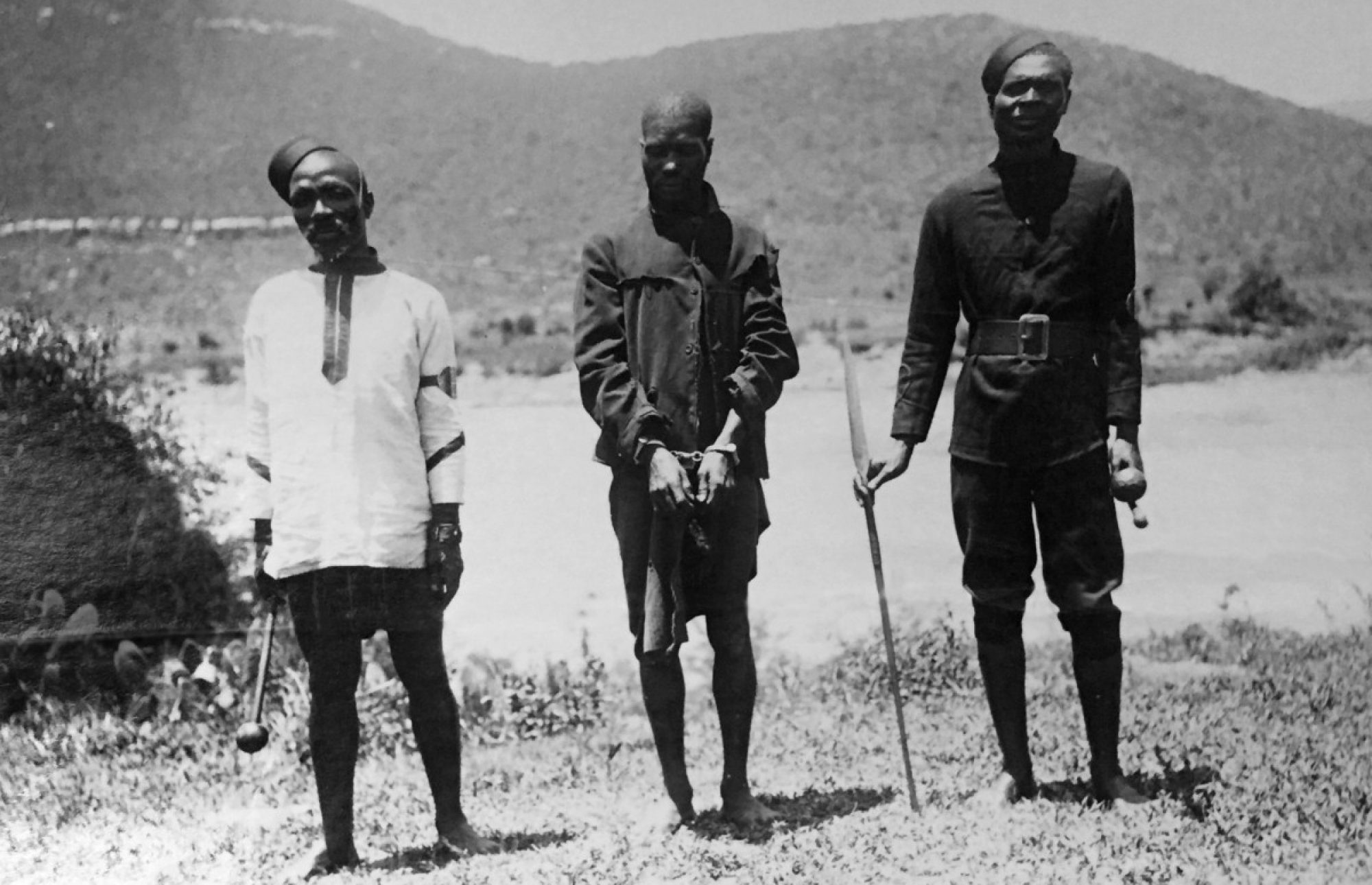

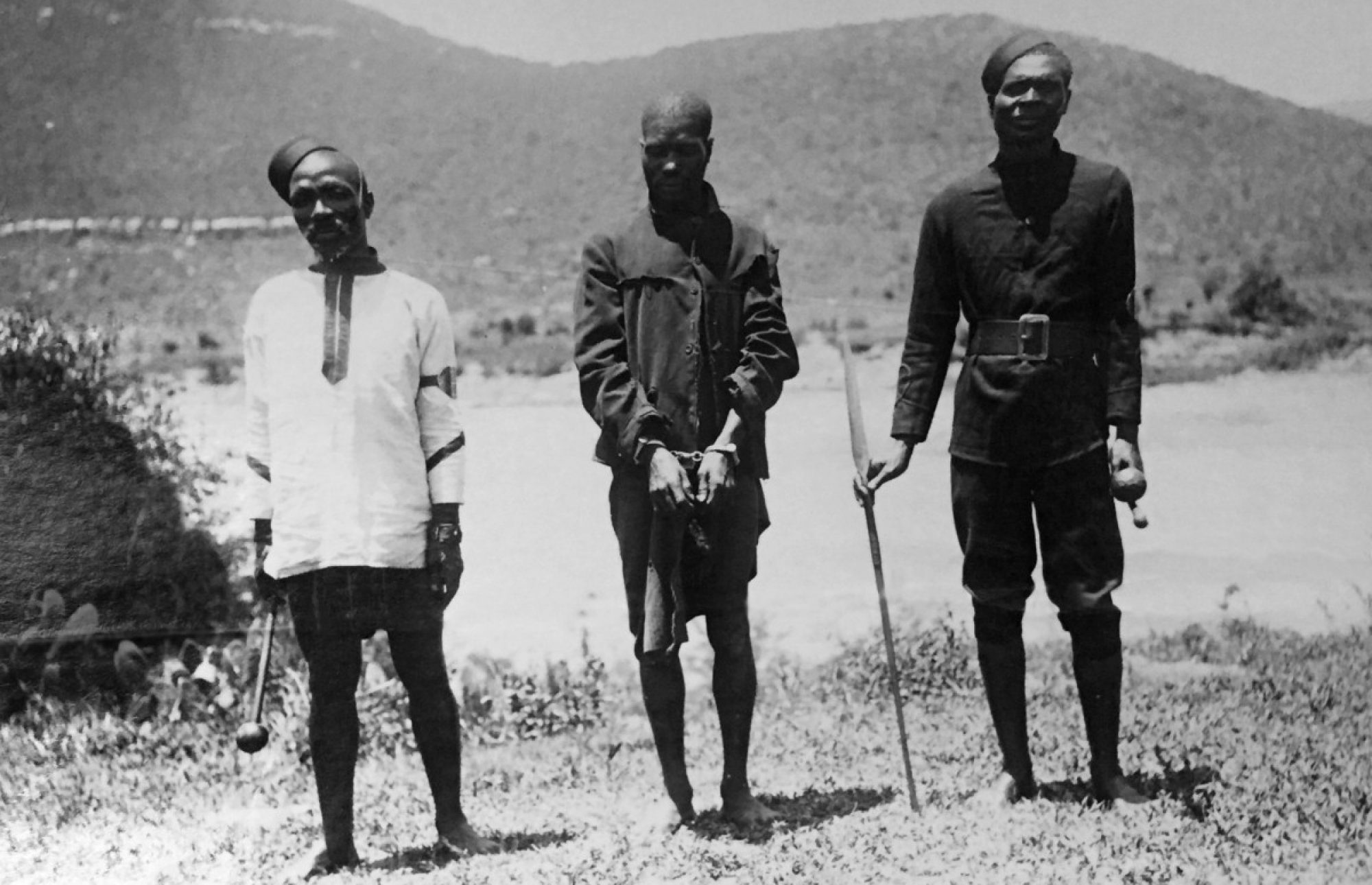

Throughout the play these viewpoints are most obviously depicted through spoken words, as used for their supporting evidence above. Furthermore, the actions of the characters, their clothing, and even the demeanor all contribute to the view for the audience of the justice system. The authors are clearly providing the viewpoint of the justice system being invalid, more specifically invalid from the view-point of the indigenous population of Kenya. As can be seen through early on in the trial, where the case being made against Kimathi is one that claims he is found in violation of section 89 of the penial code; which states that he was found in the unlawful possession of a gun (specifically a revolver). The most flabbergasting aspect of this; however, is that the white settlers are openly brandishing their own weapons, in a court of law, in front of a judge, and in a trial that states that the possession of a gun is unlawful. Furthermore, we can assume that the law is being completely unjustified as it is solely targeting the non-white population. Evidence of such can not only be seen by Kimathi being put on trial for a crime that the white settlers have no apparent trouble engaging in themselves, but also by their scrutiny placed upon the non-white populace that enters the courtroom, as even things as innocent as a stick are confiscated from them. Thus, the play is able to depict a completely unjust system of so-called justice. Where a system of corruption runs rampant on the grounds of an innocent population that is held to a higher degree of scrutiny for no valid reason and is forced into a situation that depicts them as one of criminals. Thus, the play is able to portray an important aspect of the justice system, which would normally go unseen if left to those in charge. This coincides which a Zimbabwean proverb that states that “Until the lion tells his side of the story, the tale of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.”.

Ngugi and Mugo portray the British court system as unjust, easily corrupted, and performative, qualities that offer a unified portrayal of British courts as a “trap” so to speak, particularly for non-British people. At times, this characterization comes directly from Kimathi’s mouth, such as when he says that there is no justice under imperialism. Thus, British courts are, to Kimathi and others subjugated beneath them, little more than a ridiculous exercise leading to unjust punishment, since justice in their imperialist context is impossible in any case. The authors’ employment Kimathi’s cell as the site of his “trials” is likewise a nod to the pomp of British justice, which is really dealt in money and other non-legal (necessarily) preoccupations, rather than directly in a court room. The emphasis here is that there is little justice involved; Kimathi receives offers to be saved from death (though they are most likely disingenuous and manipulative attempts at convincing him to submit to British authority) only if he pleads guilty to his crime, which would mean that he is accepting British judicial authority. This script shows that British “justice” in the colonial context more about securing submission from indigenous people and forcing them to conform to British policy than it was about protecting their rights or even assimilating them (which is not necessarily ideal, either).

Even from the initial staging of the play, we can see the shift in how Africans and white people are portrayed in the British justice system. Ngũgĩ and Mũgo describe the tension in the air between the two groups, using descriptors like aggressive settlers or educated blacks to illustrate their point. The two creators describe the imbalance of power and tension between Africans and settlers through the off-sides of the play, with the onomotopeias used by the two authors to underline the tension in the courtroom. Kimathi’s repeated silence throughout the court proceedings shares how he was defiant in a system designed to bring him down. The threats of the judge do not initially prompt him to speak, but he eventually speaks, he is confrontational to the judge. The dialogue between the judge and Kimathi shows Ngũgĩ and Mũgo’s view of the justice system, one of oppression that lies over another system of justice, which is not something that Kimathi desires to answer to during his trial. He sees that the Africans had no creation in this lawmaking, and it was a legal system built on imperialist practices and colonialism. In addition, their different treatments outside of the court share the differences in how Africans and settlers were treated within the colonial system. The Africans are deprived of all weapons as they walk into court, but one of the white settlers is allowed to point a weapon at Kimathi and other Africans, without the immediate neutrialization of the threat. White settlers aren’t seen as a threat in the play, but due to racism and other viewpoints, Africans are a threat, one that has to be kept at bay at all times. Even during Kimathi’s first trial, the way that Ngũgĩ and Mũgo craft Kimathi’s speech versus that of the lawyers is different, showing the difference between “civilized” persons and “savages”. The second and third trial show Kimathi versus business entities, but the confrontation of Kimathi and Henderson in the fourth trial is designed to show the brutality of the state. Ngũgĩ and Mũgo illustrate how the brutality of colonialism to apparent threats to British power never ended. The torture inflicted on Kimathi by the state is a device used by Ngũgĩ and Mũgo to connect readers and viewers to the past, showing that all that we know from the past is also in the present, just as Henderson delivers the final blow: the execution of Kimathi and the execution of the threat.

Ngũgĩ and Mũgo offer an image of the colonial British justice system as one riddled with what Kimathi describes as “Neo-slavery” (36), enraged white settlers willing to take justice into their own hands, and a black population that dreams of a better life, of what should be, of justice and opportunity in a more perfect world, a world without the ever-corrupted control and influence of British settlers. Ngũgĩ and Mũgo contrast the monologues of Kimathi and white members of the congregation in court, as seen on pg. 26-29, showing that the white settlers had notions regarding Kimathi and his movement that would cause a righteous outrage, but also displaying that the actions of Kimathi and his troops were reactionary– the settlers’ colonialism, land acquisition, and treatment of the people of Kenya was what spurred the movement they despised and attributed all their sufferings to in the first place. Ngũgĩ and Mũgo also subscribe, however, noticeably more eloquent soliloquies to Kimathi, in which he discusses his visions and dreams and speaks in his native tongue, invoking again and again what he and his people deserve, in his eyes, and what cannot be attained through the injustice of the British court system. While Ngũgĩ and Mũgo certainly do not make Kimathi as flawless hero, they do make him a defiant and optimistic man who was stood to face an unjust and undefeatable justice system which he was destined to become a victim of, and doing this for the sake of his “Dreams” and “Visions” (31), which allowed him to imagine and long for his homeland, as he believes it should have been.

The Trial of Dedan Kimathi offers an intimate lens into the corrupt and oppressive British justice system in Kenya. Specifically, Ngūgī and Mūgo portray this image through a series of deals proposed to Kimathi in order to elicit the surrender of the Mau Mau leaders. While Kimathi conveys his distrust and distaste for the British justice system through silence, politicians and businessman soon attempt to convert his silence into surrender. Shaw Henderson first echoes this sentiment by imploring Kimathi to plead guilty and save the life of himself and others associated with his cause. A banker, business executive, and politician soon mimic Henderson in advocating for purported stability and progress, yet at the expense of Kimathi’s multi-year resistance. Effectually dishonoring the bloodshed and perseverance of the Mau Mau struggle, Henshaw and other professionals endeavor to inspire surrender by mentioning half-hearted racial and socioeconomic advancements. These professionals, likewise, disregard any framework for due process as they advocate a guilty pleading by Kimathi in order to end the war. If Kimathi pleaded guilty, they contend, he and others of the Mau Mau movement could save their lives. Ngūgī and Mūgo, thus, effectively set the scene for Kimathi to dissent from the corruption of the British justice system by tenaciously maintaining his anti-imperialism stance. Likewise, as the trickery of the British colonists infiltrates the legal system, the platform for Kimathi to re-express his definition of justice, which is achieved through a revolutionary struggle against all the forces of imperialism, expands.

The trial excerpts begin with “a white judge presides” (page 3). This highlights the immediate corruption and bias that will be present in the courtroom. The British justice system operated with a clear separation between the races: one that benefited white colonizers and would consistently criminalize black natives.

As the trial in the courtroom continues, the self-serving and exclusive nature of the British justice system is further proven. In response to the judge stating he is simply abiding by the laws in place, Kimanthi states, “Two laws. Two justices. One law and one justice protect the man of property, the man of wealth, the foreign exploiter. Another law, another justice, silence the poor, the hungry, our people” (page 25). The British justice system was built to benefit its own citizens while simultaneously “othering” a group of people whose land, resources, and lives are being exploited.

In continuation, a settler’s outburst in the courtroom shows the privileged and entitled perspective the British have towards the Kenyan lands and peoples. A settler says, “British justice has gone beyond limits to tolerate this, this kind of rudeness from a mad, bushwog” (page 28). The British see no issue with the way they are treating the Kenyans; it is this obliviousness that allows them to be unbothered by the realities of their justice system. Since the system works in their favor, the British are adamant to make rulings that permit their power over the Kenyans to persist.

The image of the British justice system offered in The Trial of Dedan Kimathi is a strikingly brutal one — indeed, it is depicted as entirely unjust. This can be seen even from the play’s initial stage directions, in which Shaw Henderson enters “dressed as a judge . . . [appearing] to believe in his role as a judge” (24). The arbiter of justice, it seems, is entirely unqualified and unfit to be in his assigned position. He merely “believes” in his ability to fairly and objectively preside over Kimathi’s trial. A sense of belief in one’s own superiority is certainly not grounds to ensure an impartial trial. Ngũgĩ and Mũgo’s opinion is thus made evident here: that they feel as though the entire British justice system present in Kenya was a complete and utter sham. Beyond the use of stage directions, Kimathi is continually portrayed in a quasi-prophetic light, which works to create a contrast between his supposedly righteous actions and the corruptness of the justice system that seeks to bring about his demise. For example, as Kimathi talks with a judge who attempts to make him confess, he declares that “There is no order and law without / liberty. / Chain my legs, / Chain my hands, / Chain my soul, . . .” (27). That these words are written in verse is not insignificant: it helps to depict Kimathi as a somewhat otherworldly figure, capable of revelations beyond the comprehension of the broader Kenyan people. Contrast this with the judge before him, who speaks in a condescending, if not entirely oppressive tone: this certainly sheds light on the harsh, unfeeling practices of British justice officials. This rhetorical strategy was certainly employed intentionally by the play’s authors. Moreover, throughout the play, Kimathi discusses his situation with various people — all of whom instruct him to accept what he calls “neo-slavery” in favor of stability in progress. These people include figures that are relevant within Kenyan society: Shaw Henderson, a banker, a business executive, a politician, and a priest. That these influential figures would attempt to coerce a forced surrender out of Kimathi only works to strengthen the Ngũgĩ and Mũgo’s argument that the British justice system is fundamentally corrupt: it would rather force a confession than accept silence and the power associated with it.

The play goes into great depth describing the courtroom. The whites are sequestered from the black natives, who receive more scorning from the judge than the white side for murmuring. A major theme in the play is lack of due process. The defendant is assumed to already be guilty and must just confess. Most courts, specifically the prosecutors, have to show evidence beyond a reasonable doubt that the defendant is guilty. It’s lacking of a fair trail due to the defendant not even allowed in the courtroom during most of the proceedings, and also for his lack of council. Another important part is the judge threatening the defendant in contempt for not pleading guilty verbally; although this is self-incrimination. Basically, the court system in Kenya is clearly biased and disenfranchises the marginalized: the natives.

Another important part is the British’s desire to portray their presence as beneficial. The introduction of the three rich men and other characters to persuade the defendant to renounce his position and stance all serve the purpose of showing the level of brainwash the colonizers have instilled into the community. The introduction of businessman, religious icons, and family friends shows colonizing has exceeded mere geography and permeated into social and cultural spheres. Overall, the play does a great job in showing the disparities the natives and foreign-descent have in the Kenyan legal system

In this reading by Ngugi and Mugo, the British judiciary system is depicted as being corrupt. It quickly becomes apparent that there is no way to win the trial, and that it is a sort of set up – an unchangeable bias set out from the beginning.

The people are described as being separated by race; “In the court, blacks and whites sit on opposite sides. It is as if there is a huge gulf between them” (23). This power imbalance and stress between the races continues throughout the trial.

In defiance, Kimathi is silent during the trial until he is threatened by the judge saying, “I may warn you that your silence could be construed as contempt of court in which case I could order that you be sent for a certain term in jail” (25). Even then, Kimathi responds in a hostile manner, expressing his disdain for the British court system calling it “an imperialist court of law” (25).

He recognizes his lack of power and control over the situation and calls it “the law of oppression” (25) and declares that there are “two laws. two justices,” one for the wealthy explorer and another for the poor. His rebuttal receives “jubilance and excitement among the Africans [and] fury in the faces of settlers.” Ngugi and Mugo capture the scene in one word, “tension” (26). This tension expands further beyond the court and is indicative of systematic injustice and power imbalances. I am interested in hearing what the rest of our class thought of the reading and also talking about how exact it is to the real trial.

This theatrical retelling of the trials of Dedan Kimathi portray a steadfast Kimathi refusing to succumb to the imperialist legal system that threatens to send him death for his rebellion against that very system. The authors convey a picture of an unjust justice system through Kimathi’s eloquent oration from the witness stand and the harsh words of white settlers. When he refuses to plead guilty or not guilty for the crime he is accused, Kimathi responds that colonial Kenya has “two laws. Two justices. One law and one justice protects the man of property, the man of wealth, the foreign exploiter. Another law, another justice, silences the poor, the hungry our people,” highlighting the fundamentally unfair structure of the judiciary. The judge maintains that this legal system is in fact the means of maintaining justice in the region, and that the intention of this trial is to protect “civilisation… investment… Christianity… order,” four qualities that notably serve European settler interests before the native African people subject to their rule. The depiction of injustice in Kenya’s colonial legal system is encapsulated by the exchange between the judge and Kimathi; In response to Kimathi’s protest, the judge argues that “there is no liberty without law and order.” Kimathi replies, with an eloquence that portrays a wise, virtuous resister to the oppressive colonial law, that “there is no law and order without liberty.”

Ngugi and Mugo portray the British court system as unfair and corrupt. It becomes clear within the reading that there is no way to actually win the trial, since everything is partial and premeditated as various biases were set out from the beginning.

In fact, this lamentation is even directly addressed by Kimathi, as he says that there is no justice under imperialism. The British system is clearly a redundant and tedious process leading to the same premeditated result which is the unjust punishment of Kimathi since justice in their colonial context is an impossible feat regardless. The imbalance of power due to colonialism and racism is apparent in the trial. He recognizes his lack of control over the situation and even proceeds to describe it as “the law of oppression” (25) and declares that there are “two laws. two justices,” one for the colonial settlers and another for the Africans. This script shows that British “justice” in the colonial context more about securing submission from indigenous people and forcing them to conform to British policy than it was about protecting their rights or even assimilating. The play goes into great depth describing the courtroom. The whites are separated from the Africans, which also reflects a major theme of racism and prejudice in the play.

The image of the British justice system in Kenya as portrayed within The Trial of Dedan Kimathi can best be described as oppressive, unjust and biased. Ngũgĩ and Mũgo write at the very beginning in the Preliminary Notes that “The atmosphere is tense and saturated with sadness, as if the whole land is in the mourning.” Before the play even begin, the authors already hinted to the outcome of the trial and expressed their sympathies. Moving forward, the oppressive nature of the British justice system in Kenya is conveyed through the exchange between Kimathi and the judge and the characterization of the Black and White men in the court room. When Kimathi holds his brief silence to the judge, he was immediately threatened to a term in jail for contempt of court. When Kimathi challenges the judge for the legitimacy of the judicial system that favored the wealth, he was met with disdain and disrespect by the settlers. “One law and one justice protects the man of property, the man of wealth, the foreign exploiter. Another law, another justice, silences the poor, the hungry, our people. [Jubilance and excitement among the Africans. Fury in the face of settlers.]” The British imperialists defends their judicial system for the purpose of law and order, but the very law and order fails to serve the majority of the population that is the black natives whom reside the lands. The judge and the settlers enter the trial with the premeditated result that the accused the guilty, failing to serve justice to the people. The colonialism, racism and disparity of power between the two populations makes the existence of a British courtroom in Kenya meaningless.

Ngũgĩ and Mũgo built a powerful depiction of the intense trial of Dedan Kimathi. Both authors do an incredible job at portraying the strength and courage that Kimathi brought about to Kenya and how admired he was by the rest of the population. This play essentially celebrates Kimathi’s rebellious acts to submit to British Imperialism.

The play begins by stating “the white judge presides” showing the power that this white British Judge holds in Kenya and when determining the fate of Kimathi. It proceeds to illustrate how “Africans are squeeze around one side, seated on rough benches” while “Whites occupy more comfortable seats on the opposite side.” This shows that racial disparities were occurring in places that were supposed to be fair and factual, but is essentially setting the stage for the injustice fate of Kimathi.

Kimathi, however, is aware of this unfair treatment as, before the judge, he states “By what right dare you, a colonial judge, sit in judgement over me?” depicts Kimathi’s courage to defend himself in this imperialistic court (25). The judge later responds by explaining to Kimathi that there is “only one law, one justice” however, this is not the case.

The two authors are able to recreate, through their own interpretation and imagination, the events that took place through their own eyes and not through the eyes of an imperialist who viewed Kimathi as ‘vicious.’ In doing so, the authors give a voice to a voiceless character and illustrate him with robustness and fearlessness.

The Trial of Dedan Kimathi conveys a very negative view of the the British justice system in colonial Kenya. This negative view is summarized in a quote by Kimathi. He says, “I despise your laws and your courts. What have they done for our people? What? Protected the oppressor. Licensed the murders of the people: whipped when they did not pick your leaves” , and describes many other situations in which Kenyans are brutalized and killed for refusing to obey their white employers.These settlers of Kenya were given virtual impunity under British law and therefore able to enact any kind of violence upon the Native Kenyans with no repercussions or recourse. Ngũgĩ and Mũgo incorporate a potentially violent situation with a disgruntled settler to emphasize this point. First, the settler tells his story and states that he lost his family and his property because of the beliefs and ideologies of the natives. He then attempts to shoot Kimathi, but the guards stop him before he can pull the trigger. This settler acts under the assumption that he will not be in danger of physical harm if he tries to murder a Native Kenyan and he is ultimately correct in his assumption. Had the roles been reversed, the law would have justified Kimathi’s beating and/or murder.

The reconstructed trial of Dedan Kimathi highlights a key dichotomy imbedded within the African transition away from colonialism. What Kimathi so eloquently highlights atop the stand is that there existed an inherent inequality barring the full power of justice from taking hold. What is brought forth by this reading is that, within the prescribed legal channels, there existed two roads of justice; Kimathi in the reading points to the two systems of justice that existed saying “One law and one justice protects the man of property, the man of wealth, the foreign exploiter. Another law, another justice, silences the poor, the hungry our people.” By this statement, the legal system of which Kimathi was being placed on trial was inherently tipped to the colonizers; with this knowledge it becomes understandable why Kimathi refused to plea one way or the other, because the legal system was unjust and therefore illegitimate in his eyes. What these imbalanced legal systems show, is that in the context of African colonialism, the burden of Europe to bring the continent into what they deemed as the civilized world only brought forth the worst in Europeans. Through this reader Kimathi speaks to this mistreatment of authority, all with the underlying tone that the colonial stay must come to an end.

Ngũgĩ and Mũgo’s depiction of the colonial justice system is unsurprisingly negative, but there is an interesting undertone to it, which is that the British characters seem to generally believe in it and seem to be blind to the true nature of their colonialism, whereas Kimathi sees it quite differently. I believe the key distinction here is a matter of legitimacy. The British and settlers see their presence and rule as legitimate, while Kimathi does not, and that makes all the difference. One demonstration of this early on is the white settler who bemoans how bandits and banks have robbed him of all of “his” property – property he owns on a continent that is not his, inhabited by people who thought that land was theirs. The settler only looks at what is directly in front of him (and only sees things through his own self-interest) and so does not realize that others might see the situation very differently. Similarly, the British colonial authorities believe themselves to be the rightful rulers of Kenya, and that the people of Kenya need to respect that authority. Because the colonial government is legitimate, rebelling against it (as Kimathi and the Mau Mau did) is wrong, and must be punished. And that’s not an unreasonable chain of thought. The problem here is that the colonial government’s claim to legitimacy is very weak, and predicated mostly on force. They can’t cite elections, or a hereditary monarchy or a recognized religious authority. This is why the government has to work so hard to stamp out rebellion – because when native Kenyans question the British’s authority, the British have few good answers. Therefore, the questioners need to be silenced and repressed as quickly as possible.

Ngũgĩ and Mũgo show this with another fact of the case, which is that Kimathi is not on trial for his actual crime. The offense he was charged with, carrying firearms, is not what most people would consider to be a crime, and certainly not a capital one. What he is really on trial for is rebellion, which is much more serious, but harder for the prosecutors to prove, especially since they wish to eliminate Kimathi as quickly as possible. The fact that Kimathi is not on trial for his actual crime is indicative of the fact that this court system isn’t designed to distribute justice in the normal sense. It isn’t meant for the benefit of the public, or at least the native public. It certainly isn’t meant to protect citizens from government overreach and oppression. The court, in Ngũgĩ and Mũgo’s view, is clearly and exclusively a tool of the British state to maintain control over their colony. This is why Kimathi’s fate is never really in doubt – the state believes that eliminating him is crucial to its own survival, and the court isn’t going to get in the way of that.

The play The Trial of Dedan Kimathi offers a strikingly unambiguous image of the British colonial justice system as one of imbalance, injustice, and cold dismissiveness, balancing on enforced power dynamics between black and white. Such a sense is given from the very first scene, when in italics the writers note that the Africans and the whites should be seated separately, with the white settlers occupying a more comfortable space and the black audience forced into rough, tight seating. This automatically conveys a sense of imbalance within the system. Those who are white are treated reverentially and with more respect than the Africans, and this tends to play out in the actual sentencing of the time. Moreover, the power dynamics within the room also reinforce this sense of imbalance and unfairness: those holding true power are all white (the judge, the police superintendent), while those carrying out the orders are black (the clerk, the soldiers). Though this setup does indeed serve to complicate the narrative between white and black, it ultimately underlines the imbalance in power within the court room.

Moreover, the authors also provide a scathing commentary on the justice system as a whole regarding weapons. After all, the white settlers are allowed in conspicuously wearing pistols, while the Africans are patted down and deprived of anything that could even be a potential weapon, such as a stick. Ironically, the real threat of violence comes not from the African crowd—who are allowed to do no more than glare angrily, silenced and disempowered—but from an angry white settler brandishing a gun at both the crowd and Kimathi/his guards. When placed against the context of Kimathi’s trial, where he is facing death for the mere possession of a firearm, the irony is clear: the justice system protects those with the power and legal backing to cause harm.

Finally, the authors paint a visual of the courtroom as harsh and cold when they place Kimathi in his cell and denote that his trials must appear to be taking place within that cell, stating that the aura of both the courtroom and the prison cell should be just as harsh and uninviting. This speaks volumes about their image of the British justice system as one that has already passed judgement on the powerless. The bareness of the courtroom mimics the bareness of Kimathi’s cell, letting us know that he is already as good as jailed.