Gillian Crowther discusses how eating is a significant part of people’s cultures in Eating Culture: An Anthropological Guide to Food, but I would go even further to say that as a member of a French and Italian family, eating practically isour culture. One meal in Italy can last hours because Italians typically want you to truly savor the flavor of each bite and connect with others at the table. Food is a big part of both Italian and French cultures. One dish that has been a big part of my life is a soup called gumbo. My grandparents, mom, and dad grew up in Southern Louisiana where gumbo is a staple dish. We eat gumbo anytime of the year, but especially in the cooler months. Although gumbo is made year-round, anytime the smell of the roux and vegetables simmering waft up the stairs to my room, I know it is going to be a great day filled with family, talking, and soul-warming food. Mom usually begins making the roux (equal parts of flour and oil constantly stirred until it is a rich brown color) in the morning. As the roux cooks, my sister and I go down and help cut up all the vegetables and prepare the stock. The aroma is the best wakeup call. We have a great time talking all the while learning about our families’ culture. We often sing and laugh together while working on the meal. Gumbo is often said to represent the people of Louisiana and is actually the official state dish. Much like New York is described as the melting pot of America, gumbo is the melting pot representing the many cultures of South Louisiana. There is a mishmash of ingredients in gumbo, similar to how there is a mishmash of different people in the region. Louisiana has always been a second home to me. Something about the culture of Southern Louisiana makes people feel like they belong. In fact, celebrities often move there because they feel as if they are treated no differently than anyone else because just about everyone is treated the same there.

As a child, I overlooked the value and significance of gumbo in my family. Like many children, I saw it as just another food on the table. I did not see the role it played in my grandparents’ and parents’ lives before me. My grandma grew up impoverished, but gumbo was one hot meal that she could look forward to eating on some days. It was one of the first dishes my mom made my dad when they were newlyweds first living in the unfamiliar cold of Wisconsin. Gumbo was also one of the first dishes my mom showed my siblings and I how to make, wanting us to have a piece of Louisiana culture while growing up in Atlanta away from our extended family. One day we will carry on the tradition of making gumbo and teaching our children how to make this familial comfort food. I think one reason I did not have the same appreciation for gumbo as I do now is because as I have gotten older, I have more memories associated with it which makes the dish fonder to me.I like the depth of flavor that comes with a good gumbo, and a good gumbo is often dependent on a good roux.Roux is the basis of several Cajun foods. Similar to the depth of a gumbo’s roux (if it is made well and is a roux-based gumbo, at least) is the depth of meaning that this dish holds for me. The ingredients and characteristic flavors of gumbo are only a small part of why this dish is so good to me. It is the memories I tie to this dish—the contextual associations—that make it that much better to me. Every Thanksgiving, my family ships in some smoked turkey from Texas and uses the leftover pieces of the turkey to put into a rich gumbo for dinner the next two days. I remember my mom cooking gumbo over the years and giving my sister, brother, and I tips as she went about cooking it, sharing memories and advice on what to do and what not to do when cooking it. We have always laughed about the peculiar name of the Louisiana-brand spice we put into our gumbo, known as Slap Ya Mama. We have joked about the name of the brand in the kitchen while my mom has been cooking since I was little. My mom calls the roux of the gumbo “kitchen napalm” because it burns people when it gets on them, which often happens when cooking the roux. Water alone will not stop the burning, but soap and water together will do the trick. My mom has told me that she could not even begin to count the scars that have formed by making gumbo throughout her life.

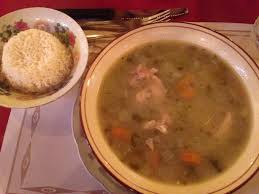

From top to bottom below: the roux of gumbo; the finished product of gumbo; my family

Gumbo is a traditional soup served over a small amount of rice. Its origins can be traced back to the various peoples that inhabited Louisiana over the centuries. Gumbo is most often made with what Louisianans call “the holy trinity”—onions, celery, and bell peppers. The influence of rice in the dish comes from Spain, and the influence of okra in the dish comes from Africa. In fact, “gumbo” actually means “okra,” and the name originates from Western Africa, which indicates that gumbo was originally meant to be made with okra. Today, people use either okra or filé powder a thickener for the dish, and sometimes both. Filé powder is crushed sassafras leaves which is an indigenous plant found in many Southern and Mid-Atlantic states. If someone wants the gumbo a little thicker, he or she can always sprinkle some more filé in the soup at the table. Gumbo is likely to have found its way into Louisiana in the 1700s, but the first references to it occurred in the early 1800s. Gumbo is traditionally prepared in a seasoned iron pot, which tends to be passed down through a family’s generations. It is the iron pot and the roux that gives gumbo its distinctive flavor. There are two main types of gumbo. There is seafood gumbo which is often made with the local seafood of Louisiana caught that day, and then there is chicken and andouille sausage gumbo, which is my personal favorite. Winter is colloquially known as “gumbo season” by people in Louisiana with people from all over the state posting pictures on social media of their gumbos on the stovetops with the caption, “It’s gumbo time!” But for my family and I, it is always gumbo time. Everyone makes gumbo a little bit differently, but I know that even seeing the word gumbo on a menu or having the slightest taste of okra mixed into a nice deep roux will remind me of home—it will not be as good as my Mom’s, though.

My mom likes to say that no self-respecting Cajun needs a written recipe for gumbo and it is just something that is thrown together in the kitchen, but the following recipe is from Commander’s Palace in New Orleans, a restaurant often frequented by my family and me during the Christmas holidays. Each gumbo is as different as the individual making it. There is no definitive recipe, but for an authentic gumbo it should have a dark roux, filé powder, the “holy trinity”, okra, a meat, and what Mom says are the most important ingredients: patience and love.

INGREDIENTS

3 cups diced onions

2 cups diced green bell peppers

1 28-oz can diced tomatoes

1 cup tomato sauce

1½ tsp thyme, dried

1½ tbsp minced garlic

4 bay leaves

½ tsp salt

½ tsp freshly ground pepper

1½ lbs frozen cut okra, defrosted (or fresh, if you can find it)

2 quarts seafood stock*

2 lbs shrimp, peeled and deveined

2 dozen oysters, shucked

1 lb lump crabmeat

2 tbsp filé powder (ground dried sasafras leaves; available at specialty food stores.)

PREPARATION

Combine onions, peppers, tomatoes with juice and tomato sauce in a heavy, 8-quart pot. Cook on medium heat for 10 minutes, stirring occasionally. Add thyme, garlic, bay leaves, salt and pepper; blend well and simmer for 10 minutes.

Add okra. When okra is bright in colour and is cooked but still crisp, add stock. Bring to a rapid, rolling boil, then lower heat. Add shrimp, oysters and crab meat and simmer for 15 minutes longer.

Combine filé powder with 1 cup of the soup liquid. Remove gumbo from heat and stir in the filé-soup mixture. Correct seasoning to taste. Serve over cooked rice and season to taste with Tabasco sauce.

*Fish or seafood stock can be found at most specialty food stores, including Whole Foods. You can also make your own by boiling shrimp shells and/or fish bones, carrots, celery, salt, pepper and onions in a large pot filled with water to cover. Simmer until the broth is flavourful; strain and use. You may also substitute chicken stock.

———————————————————————————————

Works Cited

Dry, Stanley. 2013. A Short History of Gumbo. Southern Foodways Alliance. https://www.southernfoodways.org/interview/a-short-history-of-gumbo/, accessed July 6, 2019.

McPhail, Tony. 2015. Commander’s Palace Seafood Gumbo. Western Living Recipe Finder. http://westernliving.ca/recipes/2011/11/01/commanders palace-seafood-gumbo/, accessed July 5, 2019.

.

(Picture of my Family)

(Picture of my Family) (Brought from

(Brought from