Background

Upon reading this case I immediately thought of the institutions that were built in the early 1900’s that housed the physically and mentally disabled, of all ages, in which people would admit family members as they believed they were not fit for society. These institutions, such as Letchworth Village in upstate New York, were soon discovered to be severely mistreating the patients – including techniques of horrific experimentation (Abandoned NYC). However, as this became widely accepted as unethical and immoral in the 1950’s, experts began moving people out of institutions and into communities (History of Health Treatments). In Thomas, Waluchow & Gedge’s Well and Good, case number 6.4 presents Stephen, a seven-year-old boy with severe mental disabilities. Stephen was born prematurely and shortly after suffered extensive brain damage by meningitis that left him “profoundly mentally disabled with no control over his faculties, limbs or bodily functions” (Thomas, Waluchow & Gedge, 229). Stephen has passed through the hands of many different institutions for physically disabled children and even to a foster home.

Dilemma

The three main dilemmas I found after reading this case were:

1) In such a situation, who gets to decide what is done with Stephen?

2) What are the legal rights of the mentally disabled?

3) In general, what makes it “okay” to not treat a patient?

In regards to the first question, we must turn to the principle of autonomy which acknowledges a person’s right to make choices, to hold views, and to take actions based on personal values and beliefs (Ethics Principles). In this case, Stephen lacks the cognitive capacity to make his own decision and therefore the decision should be turned over to his parents. However, the argument presented in this case is whether or not his parents should be given that right considering the fact that they are not his primary care givers and do not spend the majority of time with Stephen as the care givers in the institutions do. Some may argue that his parents hold the responsibility as they are his “next of kin” so to speak. However, in the case Justice Lloyd McKenzie claims that “the professionals who have been treating and observing Stephen since late 1982 are better qualified than [the parents] are to assess his condition and capacities because they, the parents, have hardly seen him” (Thomas, Waluchow & Gedge, 232). I agree with Justice McKenzie in putting the decision into the hands of Stephen’s caregivers.

In terms of the second question, regarding the rights of the mentally disabled, I believe the Citizens Commission on Human Rights has provided a very detailed declaration of human rights that clearly defines the rights of the mentally disabled. Some may argue that keeping Stephen alive is a waste of resources and time. However, I believe that ending Stephen’s life simply because of a disability and the immense effort necessary to keep him alive is simply inhuman. We don’t end the lives of people who are handicap because it is harder for them to perform tasks x, y, and z. Stephen was born, he is living, he is human and I believe that his rights deem it necessary to keep him alive – the declaration by the Citizens Commission states that “any patient has the right to be treated with dignity as a human being.”

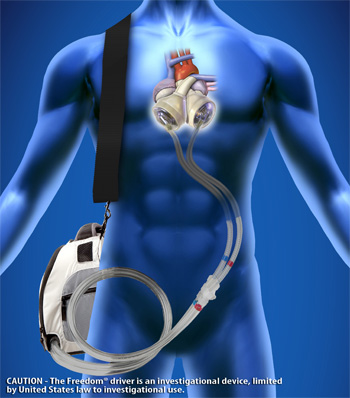

The third question addresses the principle of non-maleficence described as an “obligation not to inflict harm intentionally” (Ethics principles). In this case, although the surgery would require an “extraordinary surgical intervention,” and would “constitute cruel and unusual treatment of Stephen,” the physicians have a duty to do everything in their power to treat their patients (Thomas, Waluchow & Gedge, 230). While some may believe that the pain that Stephen would suffer is grounds for making it acceptable to end his life, I believe that we must look at the case in terms of the long term rather than the short term. For Stephen, undergoing this surgery increases his chances for survival and, therefore, I believe the surgery should be performed.

Reflection

The two main dilemmas involve the principles of autonomy and non-maleficence. In terms of autonomy, Stephen lacks the cognitive capacity to make a decision for himself and therefore his parents should be responsible for making a decision. However, since Stephen’s parents do not spend much time with him, it is believed that the professionals who have been treating and observing him are better qualified to assess his condition and capacities. On the other hand, the decision as to whether or not the surgery should be performed revolves around non-maleficence. Is Stephen better off with or without the surgery? If it were up to me, I would have Stephen’s professional caregivers assess his conditions and if they agree that the surgery, despite the short-term pain, would improve his condition in the long term then I would respect their decision.

Works Cited

Abandoned NYC . N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Feb. 2015. <http://abandonednyc.com/2012/08/05/legend-tripping-in-letchworth-village/>.<http://nwabr.org/sites/default/files/Pri nciples.pdf>

Ethics Principles. N.p., n.d. Web. 18 Feb. 2015. <https://www.nwabr.org/sites/default/files/Principles.pdf>.

History of Mental Health Treatment . N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Feb. 2015. <http://www.dualdiagnosis.org/mental-health-and-addiction/history/>.

Thomas, John and Wilfrid Waluchow. Well and Good: A Case Study Approach to Biomedical Ethics. 3rd ed. Broadview Press Ltd., n.d. Print.

to trauma accidents. This is in contrast to the relatively smaller number, 16%, who are lost to cancer. In this case, Amira, her partner Casey, and their daughter Samantha, are victims of a crash that kills Casey and injures Samantha. Meanwhile, Amira is in very critical condition and needs to quickly enter the operation room in order to save her life. However, as she goes in and out of consciousness before surgery, she asks how her family is. After quickly telling Amira that her daughter will be fine, the nurses pause to consider if they should tell her about the death of her partner.

to trauma accidents. This is in contrast to the relatively smaller number, 16%, who are lost to cancer. In this case, Amira, her partner Casey, and their daughter Samantha, are victims of a crash that kills Casey and injures Samantha. Meanwhile, Amira is in very critical condition and needs to quickly enter the operation room in order to save her life. However, as she goes in and out of consciousness before surgery, she asks how her family is. After quickly telling Amira that her daughter will be fine, the nurses pause to consider if they should tell her about the death of her partner. grounded in trust. Trust is the root of justice, a principle which a competent patient has access to. The patient must already depend on the team to save her physical body. In order to remain just, the nurses must accept that Amira is entitled to have any and all information pertaining to the status of her family. Upon disclosing the information, the nurses need to be prepared to provide moral support and to help Amira focus on her role as her daughter’s caretaker.

grounded in trust. Trust is the root of justice, a principle which a competent patient has access to. The patient must already depend on the team to save her physical body. In order to remain just, the nurses must accept that Amira is entitled to have any and all information pertaining to the status of her family. Upon disclosing the information, the nurses need to be prepared to provide moral support and to help Amira focus on her role as her daughter’s caretaker.