Background on Case

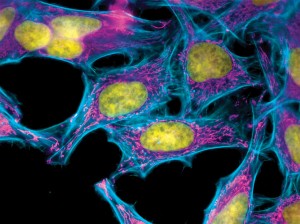

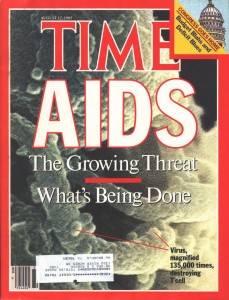

Henrietta Lacks’ case is one of the most famous cases involving non-consent and the argument over whose rights prevail. Henrietta died from cervical cancer at age 31, and a biopsy of her tumor was taken for the sake of research. Henrietta had not given permission for her cells (now known as HeLa cells) to be used for research, however this was standard in the 1950s. When researchers grew Henrietta’s cells in the lab, they divided every 24 hours and became the “most proliferated cells in history” (Skloot, p. 4). On account of this, HeLa cells were quickly passed along to other researchers and were soon being mass produced to test vaccines, such as for polio. However, the Lacks family was never compensated for Henrietta’s cells, and to this day they remain in poverty, and ironically enough, unable to afford to even see a doctor.

Argument Surrounding Protecting Patients’ Identities

While what happened in Henrietta’s case is unlikely to happen again due to the standards for providing consent, it is important to discuss the issues surrounding protecting patients’ identities. If we ignore the fact for now that Henrietta did not agree to her cells being used for research, did the researchers at least owe it to Henrietta’s family to keep her identity anonymous? While the researchers in this case nicknamed the cells HeLa and attempted to use fake names such as Helen Lane (Thomas et al., p. 255), it was not long before most of the world knew whom the HeLa cells had belonged to. Prior to the Lacks family even becoming informed that Henrietta’s cells were being widely used, they were being bombarded with publicity. If we are to respect anonymity and the right that a patient has to their own body, then the family should have been informed first of the use of HeLa cells prior to the public.

With the idea of justice, one of the primary components is respecting people’s choices. If we want to adhere to autonomy, and Henrietta was not able to give informed consent, then the most logical thing to do in the eye of justice would have been to ask the family. In order to respect autonomy, we now require informed consent. However, if Henrietta was not able to consent to her cells being used, it would have been most beneficent to inform her family and ask for their permission, and to keep Henrietta’s identity concealed. This practice has significantly improved with the mandate of HIPAA today.

Debate About Receiving Compensation for Research

Another line of argument comes from the idea of whether the Lacks family should have received compensation for Henrietta’s cells. It does seem unjust that the Lacks family neither a) gave consent for Henrietta’s cells to be used for research; b) were informed of their decision to use her cells for research and vaccination; c) not keep Henrietta’s identity anonymous; d) not provide any sort of compensation. If we look at this all together, the Lacks family was not treated through principles of nonmaleficience, as they were neglected in the decision making process and not treated fairly. Nowadays, individuals typically are compensated for participating in research. Money is often given to subjects as an incentive to get people to be in studies. Thus, it would seem logical that an individual who agrees for her cells to be used in research should receive compensation, and if she dies her family would receive the compensation on her behalf. It is difficult to set a price on the immense positive contribution HeLa cells gave to society, however the fact that the Lacks family is still so poor and received no compensation is completely unjust. So, there should have been some form of compensation or privilege given to this family that helped make science so much better.

One of the most important parts of justice to look into in this situation is the idea of decreasing vulnerability, exploitation and discrimination. The economically disadvantaged are often taken advantage of, and this is exactly what happened in Henrietta’s case (Beauchamp & Childress, p. 267). In order to be just and to eradicate any sort of exploitation of the vulnerable populations, a better method needs to be determined for there to be nonexploitative, fair payment for services.

Resources

Rebeca Skloot, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (New York: Corwn Publishing, 2010), 4.

Tom L. Beauchamp and James F. Childress, Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford UP, 2009. Print.

Thomas, John, Wilfrid J. Waluchow, and Elisabeth Gedge. Well and Good: A Case Study Approach to Health Care Ethics. 4th ed. N.p.: Broadview, 2014. Print.