In the past decades, the doctrine of informed consent has slowly changed the medical practice form “paternalistic standard” to a more “patient centered” standard of care. Today, the topic of informed consent has become a center of controversy because it hardly remains what its original purpose was. When the idea of patient centered standard was first introduced after the historical case of Canterbury vs. Spence, Judge Robinson based his decision on one key point: “Autonomy rights” in which the patient has a right to participate in the decision making process of his own medical treatment. In his decision, Robinson specified that the burden to educate the patient is on the physician; prior to any medical procedure, the physician should disclose to the patient, not only the nature of the procedure, but also the associated risks, alternatives treatments and potential benefits of the procedure. Hence, the primary aim of the informed consent was to involve and educate the patient about his own health care, and foster a dialogue between the physician and patient towards future treatment possibilities. However, today, the process of informed consent has lost its educational segment and is merely seen as a process of signing a legal “release” in case of medical negligence. This shift in the ideology of the process has caused both the physicians and patients to suffer and has hurt the entire medical profession in a big way. Over the years, patients have become confused and paranoid about the whole informed consent practice and, ironically, by adding possible negative outcomes on the consents, physicians themselves have educated patients of many more medical liabilities than they were previously aware of. Today, patients feel the victims of the informed consent process, and many have lost respect for the medical field in general. This is due to the fact that most informed consent processes are there to protect the interests of physicians and surgeons, and hardly any protect the patients and meet the needs of their families.

In order to regain the true essence of the informed consent, based on patient-physician trust, Physicians need to provide their patients with the proper information they need to know so that they also understand the possible consequences of their treatments. The ideal decision making process, according to Lidz et, al, should have four elements: 1. Information is disclosed to patients by their physician, 2. Physicians make reasonable efforts to explain the procedure to the patient and make sure that patient understands the procedure completely, 3. Patient makes the decision for or against the procedure, 4. Patient makes the decision willingly. In a New York Times article: Treating Patients as Partners, by Way of Informed Consent, thttp://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/30/health/30chen.html?pagewanted=all, Dr. Eric D. Kodish,, chairman of bioethics at the Cleveland Clinic, said, “the choreography of informed consent, [is about] how you make eye contact, sit down, build trust.” Is it still possible to rebuild this trust based on mutual honesty, for solely ethical and medical reasons?

References

Canterbury v. Spence, 464 F.2d 772 (D.C. Cir. 1972).

Charles W. Lidz, Ph.D., Alan Meisel, J.D., Marian Osterweis, Ph.D., Janice L. Holden, R.N., John H. Marx, Ph.D. and Mark R. Munetz, M.D. “Barriers to Informed Consent.” Arguing About Bioethics. Ed. Stephen Holland. London: Routledge, 2012. 93-104. Print.

Chen, Pauline. “Treating Patients as Partners, by Way of Informed Consent.” The New York Times. N.p., 30 July 2009. Web. 10 Feb. 2014. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/30/health/30chen.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0>.

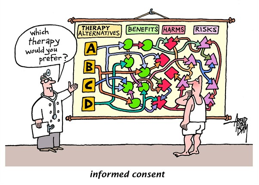

“Informed Consent.” Cagle Post RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 Feb. 2014. <http://www.cagle.com/tag/informed-consent/>.

I agree with you that the practice of informed consent has become a more legal consideration rather than an educational tool. Additionally , it is true that the doctor-patient relationship has shifted over the past 40 or so years. I believe that the relationship has shifted in a more toward a negative direction than a positive direction due to our culture and societal shifts.

The ideology and intention of involving the patient in their healthcare decision making was a positive change, but putting the burden on the physician was a mistake, which led to informed consent being more of a legality. Somewhere along the way our culture changed the attitude and expectations of medicine to be an instant fix, customer based business model. Patients now expect to walk into a physicians office and be treated like a valued customer and some even think that their time is more precious than the physicians. This has also caused physicians to turn their practices into a business to the point that they need someone to manage just the business side of their practice. And so, in the business world, “time is money.” I believe that there has been shift from a personal, care giving, and compassionate profession to that of an corporate mindset.

This shift in mindset has made the process of informed consent less of an educational tool. In order to reorient the process of informed consent, I think that both parties should be responsible, not just the physician. A physician should inform a patient about their disease and give them resources to research the information if they so choose. And they can make a follow up appointment to ask questions based on the reading and information that they learn. Then they can make a final decision. Informed consent needs to be a two-sided processes so that the patients can’t just blame the physician.

I really like the points you highlighted about informed consent and the physicians duty to tell the patient what is happening. I also like the quote from Dr. Eric Kodish that refers to the trust that a patient gives to a doctor. That is a recurring problem in healthcare right now, the lack of physician-patient trust and honesty.

As healthcare becomes more demanding and time-consuming for physicians, they tend to spend less and less time with their patients. Some physicians give an average of 17.9 minutes to each patient and then moves on to the next patient. The doctor does not have ample time to explain procedures, answer questions, or just talk to the patient to discuss issues that may erupt or fears of the patient. A great book I read called “The Heart Speaks” by Mimi Guarneri focuses on the many challenges of not having time to really get to know a patient. This lack of time is what causes a rift between patient and physician communication.

I believe that if physicians spend more time with patients explaining the drawbacks of a procedure and the benefits, the patient will be more inclined to choose what will be best for his health. One cannot provide a patient with heart disease an armful of pamphlets and explain what a coronary bypass is, explain the risks, and then expect the patient to understand the pros and cons. Just like physicians were taught a simpler, more understandable way in explaining medical procedures or ailments, they can also find ways to explain to a patient all the pertinent information that is required.

This also is a two-way highway where the patient also needs to be open-minded and able to listen to the physician and ask questions when needed. The physician is their best option; reaching out to family and friends may be beneficial emotionally, however it may bring about faulty data and information that may negatively impact a patients decision.

I feel as if the idea of informed consent revolves too much around the physician and his or her duties as a medical professional when treating a patient. Yes, I agree that the physician should disclose associated risks for various procedures and medications, but what about the patient? Shouldn’t they take an active role in educating themselves about their disease or condition? Patients have access to numerous reliable, accredited resources, like webMD, the NIH, and the CDC, that can tell them almost everything they need to know and more. Even though the medical expertise of the patient is not the same as the physician, the patient can still come in with a working knowledge of what is going on in regards to his or her body. I think this would especially help physicians when they are explaining pros and cons to medical treatment. It would be in the best interest of the patient to learn about his or her condition beforehand because it could also avoid issues of bias from the physician. By educating themselves and taking into account what the doctor tells them, patients can make well-informed decisions about their treatment. It is a mutual decision between the patient and physician, not solely one or the other.

I truly enjoyed your historical reference because I think you tied it in perfectly. Your point that said, “today, the process of informed consent has lost its educational segment and is merely seen as a process of signing a legal “release” in case of medical negligence,” was extremely on point. I also believe that nowadays doctors disclose informed consent simply because they have to, and not necessarily because they want their patients to be educated and knowledgable about what they’re putting into their bodies. In fact, I think that if it was up to the doctors, they wouldn’t want to inform their patients at all because no doctor wants to be questioned by his or her “uneducated” patient.

This “shift in ideology” that you talk about is true. However, I don’t think that it’s really made such a huge affect on the medical system as you make it seem like. I don’t think that patients feel “victimized” by informed consent because really, it’s for their benefit. According to Lidz’s article, there were many people who desired knowledge about their treatment and medication. On the other hand, there were also many who simply wanted to stay out of it. I believe that doctors should inform their patients with the basics that they would understand, and if the patient asks for more, they should disclose everything. It should be more of a conversation between the doctor and patient as opposed to just a couple of comments from the doctor.

I definitely agree with your claim that informed consent has become more of a legal formality than a process that is meant to sincerely educate the patient. It makes sense that placing the burden on doctors hurts the intent of informed consent because it becomes more about the doctor/the office/the corporation looking out for itself for fear of legal repercussion. It seems that today there is not even much of a discussion of the risks, just a handing out of papers and pamphlets that disclose all of the potential risks. As was stated in a previous comment, in today’s society it is very easy for a patient to “google” (or have someone else “google”) information about the risks, etc. associated with a procedure. With that being said, I think burden should be placed equally on the patient as it is on the doctor. We entrust that doctors will decide what they think is best for us, but as individuals, we have the ability to pursue some of the knowledge for ourselves. Should a patient come across any concerns or risks not brought up by a doctor by performing a simple web search, they should bring these concerns up with their doctor so that a meaningful dialogue may be held. After all, a dialogue is supposed to be a conversation between two people, not just a one-sided spewing of facts from a doctor.

I really enjoyed reading this argument and definitely agree with the statement that, “… today, the process of informed consent has lost its educational segment and is merely seen as a process of signing a legal “release” in case of medical negligence.” This quote really symbolizes the difference between the original idea of informed consent and what is has turned into. I agree that Doctor’s hand these documents to their patients because they have to, not because they truly care about the patient’s well-being. Also, some patients do not take the forms seriously and skim over them or just unknowingly agree to what is being done; which is unwise. I think the best way to reform informed consent would be to have Doctor’s encourage patients to truly learn about their procedure and thoroughly read the consent forms. Making this change seems hard to accomplish, but with further media on consent a greater awareness of the problem will occur. Also, I am not opposed to the idea mentioned in another argument regarding hiring a medical educating staff to both inform patients of the procedures they will be undergoing and encourage individual research to be done. Though it is seemingly costly, hiring a medical educating staff would both eliminate the physician’s burden and the patient’s fear of the consent forms.

The discussion of placing the responsibility on the informing of the patient in the hands of the doctor brings up interesting ideas. Many students are being swayed away from medical school, for both financial reasons and the stress related to the job (time, number of patients, risky procedures, etc). Malpractice suits are becoming more prominent, and many doctors wander why they are the target of so much criticism. In an optimistic perspective, doctors became doctors because they wanted to help people and they love medicine; therefore, we need to create an environment where doctors can be doctors without so much fear of legality.

I believe there needs to be an infrastructure change that adds a new educational component to hospital and doctor visits, and whether it be a new middle man job position between an MD and the patient that can be debated. Intermediate medical professionals such as nurse practitioners or physician assistants could be trained to fill an education role, where they offer education and personal support for patients. I don’t believe patients have enough knowledge or resources to educate themselves, and our health care system needs to support patients in increasing their health literacy. An educational element will remove some of the responsibility and burden placed on medical doctors, who are suffering from a tremendous amount of stress and responsibility as they try to save lives and avoid malpractice suits.

Our healthcare system is weak in many areas, and this time of change offers us an opportunity to create a system to help doctors and patients more.

While I do agree that the meaning of the informed consent doctrine has been lost overtime, unfortunately, there is no easy fix. Despite the steps to decision-making laid out by Lidz et al, the question that still remains unanswered is, “when does physician expertise override patient autonomy?” Many medical cases are not clear cut, making it challenging to develop a model that tells physicians in which situations to honor patient autonomy. For example, in some cases, patients are seen by multiple doctors and experts over an extensive period of time. Under these circumstances, it would be nearly impossible to keep patients fully informed and allow patients to agree to every decision being made about their course of treatment. In addition, it is often difficult to determine the rationality of a patient regarding a severe, even life-threatening medical decision. In such cases, patient autonomy comes into conflict with physician ethics and even legal responsibilities. Therefore, because every situation is so diverse and complicated, I believe that the informed consent doctrine may need to be applied to each case differently. While the doctrine has its clear flaws and must be further defined, many patients value the concept of informed consent that allows them to take part in their course of treatment.