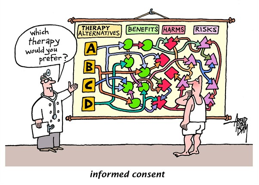

In the past decades, the doctrine of informed consent has slowly changed the medical practice form “paternalistic standard” to a more “patient centered” standard of care. Today, the topic of informed consent has become a center of controversy because it hardly remains what its original purpose was. When the idea of patient centered standard was first introduced after the historical case of Canterbury vs. Spence, Judge Robinson based his decision on one key point: “Autonomy rights” in which the patient has a right to participate in the decision making process of his own medical treatment. In his decision, Robinson specified that the burden to educate the patient is on the physician; prior to any medical procedure, the physician should disclose to the patient, not only the nature of the procedure, but also the associated risks, alternatives treatments and potential benefits of the procedure. Hence, the primary aim of the informed consent was to involve and educate the patient about his own health care, and foster a dialogue between the physician and patient towards future treatment possibilities. However, today, the process of informed consent has lost its educational segment and is merely seen as a process of signing a legal “release” in case of medical negligence. This shift in the ideology of the process has caused both the physicians and patients to suffer and has hurt the entire medical profession in a big way. Over the years, patients have become confused and paranoid about the whole informed consent practice and, ironically, by adding possible negative outcomes on the consents, physicians themselves have educated patients of many more medical liabilities than they were previously aware of. Today, patients feel the victims of the informed consent process, and many have lost respect for the medical field in general. This is due to the fact that most informed consent processes are there to protect the interests of physicians and surgeons, and hardly any protect the patients and meet the needs of their families.

In order to regain the true essence of the informed consent, based on patient-physician trust, Physicians need to provide their patients with the proper information they need to know so that they also understand the possible consequences of their treatments. The ideal decision making process, according to Lidz et, al, should have four elements: 1. Information is disclosed to patients by their physician, 2. Physicians make reasonable efforts to explain the procedure to the patient and make sure that patient understands the procedure completely, 3. Patient makes the decision for or against the procedure, 4. Patient makes the decision willingly. In a New York Times article: Treating Patients as Partners, by Way of Informed Consent, thttp://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/30/health/30chen.html?pagewanted=all, Dr. Eric D. Kodish,, chairman of bioethics at the Cleveland Clinic, said, “the choreography of informed consent, [is about] how you make eye contact, sit down, build trust.” Is it still possible to rebuild this trust based on mutual honesty, for solely ethical and medical reasons?

References

Canterbury v. Spence, 464 F.2d 772 (D.C. Cir. 1972).

Charles W. Lidz, Ph.D., Alan Meisel, J.D., Marian Osterweis, Ph.D., Janice L. Holden, R.N., John H. Marx, Ph.D. and Mark R. Munetz, M.D. “Barriers to Informed Consent.” Arguing About Bioethics. Ed. Stephen Holland. London: Routledge, 2012. 93-104. Print.

Chen, Pauline. “Treating Patients as Partners, by Way of Informed Consent.” The New York Times. N.p., 30 July 2009. Web. 10 Feb. 2014. <http://www.nytimes.com/2009/07/30/health/30chen.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0>.

“Informed Consent.” Cagle Post RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 9 Feb. 2014. <http://www.cagle.com/tag/informed-consent/>.