Biography

Yehuda Amichai, uncrowned poet laureate of the State of Israel, was born Ludwig Pfeuffer to Orthodox Jewish parents in Würzberg, Germany, on May 3, 1924. He received a formal Jewish education rich in the Biblical and rabbinical tradition and became familiar with the Hebrew language through study and prayer. Amichai would later draw on his early intimacy with his Jewish heritage with irreverent religious imagery and the intense God-driven narratives which form a critical pillar of his opus.

In 1936, Amichai immigrated with his entire extended family to Mandate, Palestine, then a British colony, landing briefly in Petach Tikvah (an agricultural settlement near Jaffa) before settling in Jerusalem. During World War II, he served in the British army’s Jewish Brigade; it was in wartime, stationed in Egypt, that the young Amichai began seriously exploring poetry. He was particularly attracted to the modern English poetry of W.H. Auden and T.S. Eliot, who, together with the German romantic poets, would strongly influence him throughout his poetic career.

After his discharge from the army, Amichai joined the elite Palmach force, which was fighting for the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine. In 1946, he assumed his new last name, which translates to “my people lives.” Amichai again took up arms during the 1948 War of Independence and did so again in the Sinai War (1956) and the Yom Kippur War (1973). The ubiquity of war in Israeli life and its interplay with the nation’s stubborn dreams of peace make up one of the most significant currents in Amichai’s poetry (see Nationalism). As he wrote,”I have never written a war poem that does not mention love in it, and I have never written a love poem without an echo of war” (“Obituary”).

After the war of 1948, Amichai attended Hebrew University, taking courses in literature and Biblical studies. In 1955, a year before he graduated, Amichai completed Achshav u-beyamim Acherim (Now and in Other Days), his first collection of poetry, which was published by the avant-garde Hakibbutz Hameuchad House. The impact of this slim volume has been described as revolutionary. Amichai’s utilization of colloquial rhythm and vocabulary, a sharp break from the formalism of pre-state authors, effectively wrenched the Hebrew language from its Biblical slumber into the more cosmopolitan tribulations of the modern State of Israel.

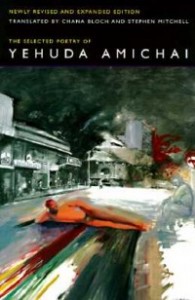

Amichai went on to publish numerous collections of poetry in Hebrew as well as plays, essays, novels, and children’s books, over a 46-year career. His work has been translated into over forty languages, including Chinese, Arabic, and Catalan. He was awarded, among other honors, the 1982 Israel Prize, his nation’s highest award for cultural achievement, and foreign honorary membership of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1986. Until his death, he was a perennial favorite for the Nobel Prize. Amichai passed away of cancer in Jerusalem on September 22, 2000, survived by his second wife Chana and his three children.

Themes

Amichai, like many other postcolonial writers, engages in a dialogue with history that forces the monumental events of the world’s historical narrative to be responsible to the individual histories of those who lived through them. He seeks to elucidate, in Federico Garcia Lorca’s words, “The drop of blood that stands behind the statistics.” Consequentially, Amichai refuses to glamorize or gloss over the tragic, putrid nature of war and pain, just as he refuses to justify one historical misdeed with another. His insistence that “I fell in the terrible sands of Ashdod” along with his comrades-in-arms displays such a terrible grief that any contemporary glorification of the War of Independence is stopped dead (“Since Then”). While Amichai recognizes the inadequacy of mere words in the shadow of tragedy, nevertheless he continues to bear witness in verse.

Amichai does not limit himself to modern, Israeli history; he bears the burden and joy of the three thousand-year-old Jewish tradition, and he offers his commentary on the entirety of the Jewish experience. Using imagery from the Bible, the prayerbook, and the mystical tradition, Amichai reveals the struggle of contemporary Israeli secularism: to draw from the richness of the Jewish heritage (especially in its greatest bequest, the modern State of Israel) without falling into the claptrap of religiosity. Amichai, after all, was a committed secularist, yet he never ceased his dialogue with God. While satirizing the establishment of religion (“Searches for a kid or for a son were always/ The beginning of a new religion in these mountains”), his tradition is still the deepest and most frequent source of allusion in his verse (“An Arab Shepherd”).

Yet, while Amichai, as the scion of a persecuted religion, often engages in the poetry of persecution, his task is that of a returning exile rather than that of a newly-freed native. The differences extend from choice of language to scope of responsibility. Many postcolonial writers from areas such as South Asia and the Americas resent the imposition of the former colonizer’s tongue; Amichai’s Hebrew, on the other hand, is a reclaiming of his birthright. Other writers have particular responsibilities to their home communities, to tell the stories that the colonizers never countenanced; Amichai, however, finds himself bound not only to the entirety of the Jewish people but to his Arab brethren as well, and, indeed, to the broadest spectrum of humanity (see Language).

Barring all suggestions of history, religion, or politics, Amichai is one of the world’s most intimate and stunning love poets. He unabashedly displays his passion:

I want once more to have this longing

until dark-red burn marks show on the skin.

I want once more to be written

in the book of life, to be written

anew every day

until the writing hand hurts. (“I Passed A House”)

One notices that even in his least guarded exclamations of love, Amichai employs astoundingly scriptural imagery. He cannot escape from his history, which is his identity, even if he would want to.

Style

Amichai’s absolute mastery of the Hebrew language is both astonishing and exhilarating. One of the most striking features of his work is his tendency to switch, at random, between biblical, formal, and colloquial diction. As Robert Alter explains:

[Amichai’s poetry] has involved not merely the sounds and idiomatic pattern and associations of the Hebrew words he uses but also a literary history that goes back three thousand years…. These are usually invisible in translation because the scale of diction operates rather differently in English, having more to do with social hierarchies and less to do with the historical stratification of the language…. Any Hebrew reader will recognize [if a] term belongs to the poetic layer of biblical language and so will immediately sense a heightening of style. (28-9)

Amichai’s verse is unusually compact, owing much to the natural terseness of the Hebrew language. Hebrew tends to combine multiple words, even complete sentences, in mazes of contractions, prefixes, suffixes, and gender. This compactness allows for an impressive paradox: immediate efficacy for those needing punch and a wealth of hidden meanings for those who love to pull words apart.

Writing in the language of the Torah, Amichai is incredibly well-poised to make use of allusion and puns. While these devices do not come across as well in translation, they lend an air of sophistication and scholarship to even the simplest of poems. The complicated, personal, and innovative imagery inherent in Amichai’s poetry translates much better, and is doubtlessly responsible for captivating many a reader. In one poem he compares his mother to a windmill, with “Two hands always raised to scream to the sky/ And two descending to make sandwiches” (“For My Mother”). In another he writes, “You are beautiful, like prophecies/ and sad, like those that come true” (“A Majestic Love Song”).

Amichai’s poems often embrace opposites: holy and profane, Israeli and Arab, love and war. He uses quotidian objects to convey a sense of the grand as easily as he employs Biblical references to describe an everyday excursion. In allowing himself a firm grasp of daily reality, Amichai avoids the didactic, inflated poetics of the early Zionist movement and, in so doing, thrusts the Hebrew language out of the postcolonial, post-diaspora shadow and into the living spotlight.

(See also Jews in India)

Selected Bibliography

Books Published in Hebrew

- Amichai, Yehuda. Now and in Other Days. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 1955. [Achshav u-beyamim Acherim] (poetry)

- —. Two Hopes Away. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad, 1958. [Be-Merhav ShteiTikvot] (poetry)

- —. In the Public Garden. Jerusalem: Achshav, 1959. [Ba-Gina Ha-Yziburit] (poetry)

- —. In This Terrible Wind. New York: Schocken, 1961. [Ba-Ruach Ha-Nora’ahHa-Zot] (poetry)

- —. Journey to Nineveh. Jerusalem: Achshav, 1962. [Masa Le-Ninveh] (play)

- —. Not of this Time, Not of this Place. New York: Harper & Row, 1968. [Lo Me-Achshavlo Mi-Kan] (novel)

- —. Poems 1948-1962. New York: Schocken, 1963. [Shirim 1948-1962] (poetry)

- —. Bells and Trains. New York: Schocken, 1968. [Pa’amonimVe-Rakavot] (plays and radio scripts)

- —. Now in Noise. New York: Schocken, 1969. [Achshav Ba-Ra’ash] (poetry)

- —. Not to Remember. New York: Schocken, 1971. [Ve-Lo Al Manat Lizkor] (poetry)

- —. To Have a Dwelling Place. Tel Aviv: Bitan, 1971. [Mi Itneni Malon] (novel)

- —. Behind All This Hides a Great Happiness. New York: Schocken, 1974. [Me-AhoreCol Ze Mistater Osher Gadol] (poetry)

- —. Time. New York: Schocken, 1977. [Zeman] (poetry)

- —. Numa’s Fat Tail. New York: Schocken, 1978. [Ha-Zanav Ha-Shamen ShelNuma] (children)

- —. Great Tranquillity. New York: Schocken, 1980. [Shalva Gedola: ShelotU-Teshuvot] (poetry)

- —. Hour of Grace. New York: Schocken, 1982. [Sha’at Hesed] (poetry)

- —. Of Man Thou Art, and Unto Man Shalt Thou Return. New York: Schocken, 1985. [Me-Adam Atah Ve-El Adam Tashuv] (poetry)

- —. The Fist Too Was Once an Open Hand with Fingers. New York: Schocken,1990. [Gam Ha-Egrof Haia Pa’am Yad Ptuha Ve-Etzbaot] (poetry)

- —. Open Eyed Land. New York: Schocken, 1992. [Nof Galui Eyinaim] (poetry)

- —. Achziv, Cesarea and One Love. New York: Schocken, 1996. [Achziv, KeisariaVe-Ahava Ahat] (poetry)

- —. Open Close Open. New York: Schocken, 1998. (poetry)

Translations

Translations of many of the above works have been published in English by Schocken (Tel Aviv); HarperCollins, Harper & Row, Harper Perennial (New York); Kol Israel (Jerusalem); and Sheep Meadow (New York).

Critical Pieces

- Abramson, Glenda. The Writing of Yehuda Amichai: A Thematic Approach. Albany: SUNY Press. 1994.

- Alter, Robert. “The Untranslatable Amichai.” Modern Hebrew Literature 13, (Fall-Winter 1994): 28-9.

- Cohen, Joseph. Voices of Israel: Essays on and Interviews with Yehuda Amichai, A.B. Yehoshua, T. Carmi, Aharon Appelfeld, Amos Oz. Albany: SUNY Press, 1990.

- “Edward Hirsch: Poet at the Window.” The American Poetry Review (May-June 1981): 44-7.

- Soloff, Naomi. “On Amichai’s El Male Rachamin.” Prooftexts 4.2 (May 1984): 127-40.

- Stiller, Nikki. “In the Great Wilderness.” Parnassus: Poetry in Review 11.2 (Fall-Winter 1983, Spring-Summer 1984): 155-68.

- The Experienced Soul: Studies in Amichai. Ed. Glenda Abramson. Boulder, CO: Westview, 1997.

Related Links

“God Has Pity on Kindergarten Children”: From an online anthology, “Poems for the Time,”compiled by Alicia Ostriker at MobyLives

http://www.mobylives.com/Ostriker_anthology.html

Two poems: “A Dog After Love” and “I Have Become Very Hairy,” from Nerve.com.

http://www.nerve.com/Poetry/Amichai/dogAfterLove/

Author: Ari Bookman, Fall 2001

Last edited: May 2017

2 Comments

Dear Ari Bookman

I just wanted to let you know that Yehuda Amichai, alias Ludwig Pfeuffer, did not emigrate to Palestine until the summer of 1936 [Würzburg Archive and personal communication]. Please correct this, and your article will be perfect.

Best regards,

Amadé Esperer

esperer@arielart.de

http://www.ariel-art.com

Hi Amadé,

Thank you for providing us with that information. I have updated the date on the page.

Best,

Mike