Biography

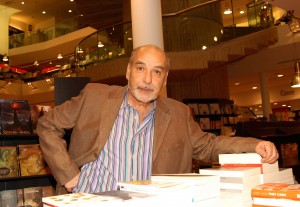

Born in Fez, Morocco to a shopkeeper and his wife in December of 1944, Tahar Ben Jelloun is one of North Africa’s most successful post-colonial writers. Winner of France’s Prix Goncourt, Ben Jelloun moved at eighteen from Fez to Tangier where he attended a French high school until enrolling at the Université Mohammed V in Rabat in 1963. It was at the university where Ben Jelloun’s writing career began. Exposed to the journal Soufflés (Breaths) as well as the journal’s founder, poet Abdellatif Laabi, Ben Jelloun completed his first poems, publishing his first collection, Hommes Sous Linceul de Silence, in 1971. After completing his philosophy studies in Rabat, in 1971, Ben Jelloun immigrated to France. In France, he attended the Université de Paris, receiving his PhD in psychiatric social work in 1975. Along with providing material for his dissertation, La Plus Haute des Solitudes, Ben Jelloun draws upon his experience as a psychotherapist for his creative writing. His second novel, La Reclusion Solitaire (later Solitaire), is a fictionalized account of some of his patients’ dysfunction which was written in 1976. Between 1976-1987 Ben Jelloun was regularly published and received awards, but it was not until his novel L’Enfant de Sable, (later translated as The Sand Child) that he became well-known and recognized, all of his novels after The Sand Child were translated into English. The sequel to L’Enfant de Sable, La Nuit Sacree or The Sacred Night, is the work for which he received his most notable award, the Prix Goncourt in 1987. Ben Jelloun now lives in Paris with his wife, Aicha, and his daughter, Merieme.

Themes

Language

The use of language is an interesting factor in Ben Jelloun’s work. Critics have maintained that Ben Jelloun is catering to a French audience. After all, although Ben Jelloun is Moroccan and Arabic is his native language, he chose to write in French. Likewise, in his novel Les Yeux Baisses, a young Moroccan girl becomes enamored with the French language and wishes to be a French writer. Some say it is difficult not to parallel this character’s situation with Ben Jelloun’s. Ben Jelloun simply declares, though, “When I started to write it came normally to write in French… I feel freer when I write in French.” From this statement and others such as “Arabic is my wife and French is my mistress; and I have been unfaithful to both,” it is obvious that bilingualism is an integral part of his life as well as a theme in his works. Regardless of Ben Jelloun’s inclination towards French or lack thereof, he is quite clever in incorporating languages into his writings. For instance, in La Nuit Sacree, he refers to a woman waiting on people in the restroom as L’Assise which in French means “the seated woman” and which in Arabic is translated into gellas, the title given to women who sit and wait on those in the restroom. This use of duality of languages adds to the complexity and sophistication of his pieces.

Moroccan Culture

Although the language for some readers may be an obstacle, others argue that it is Ben Jelloun’s incorporation of Moroccan culture into his texts which alienates readers. Situations unfamiliar to his audience may be difficult to relate to; therefore his stories may lose some legitimacy. An obvious example is that of pretending that one’s daughter is a son in order to preserve one’s property and maintain one’s prestige. Although this probably seems foreign to most, one could argue that the themes of gender identity and the way in which it relates to power and societal structure are pervasive throughout all cultures (see Gender and Nation, Third World and Third World Women). If the reader does not agree with this statement, he can simply take Ben Jelloun’s work as an entertaining tale rather than a social commentary. However, it is just this latter aspect of Moroccan incidents or references that are disturbing for some critics. Not only does Ben Jelloun write about Moroccan situations that may be seen by others as nonsensical and/or uncivilized, but he openly criticizes them. Although this has resulted in the praise by, for example, women’s groups, critics protest that Ben Jelloun defends and appeals to Europeans through stereotyping and a skewed perception of Morocco.

Surrealism

It has been said that Ben Jelloun is primarily a poet; therefore his writing style resembles that of a poet. His work is concise, yet full of poetic images and lyrical language. Ben Jelloun is a story teller, but he also allows the reader to become involved in his magical world. Dream-like states, hallucinations, and allusions to Andre Breton and the exquisite corpse each give Ben Jelloun’s work a magical intoxicated quality. Unreliable narrators and different points of view of the same story add to the mystical atmosphere as well. Ben Jelloun ends L’Enfant de Sable with, “If any of you really wants to know how this story ended, he will have to ask the moon when it is full. I now lay before you the book, the inkwell, and the pens.” This creative space for doubt and wonder gives the piece a surrealist quality. After all, it may have simply been a fanciful tale, it may have been a true story. One is not quite sure, as in the tradition of Magical Realism.

Sexuality/ Dysfunction

In light of his doctoral research on the relationship between sexuality and immigration for North African male workers in France, it is clear that Ben Jelloun is quite interested in sexuality and dysfunction. The majority of his works have the protagonist suffering from some sort of dysfunction whether it be sexual, as in L’Enfant de Sable or more physical, as in L’Ecrivain Public.

The Sand Child/Sacred Night

Ben Jelloun’s first book translated into English, The Sand Child, catapulted him into the literary spotlight. The themes of gender identity and a male-dominated society, of masking and storytelling, and surrealism provide the backdrop for a surreal story of secrets, sexuality and identity. The main character, Ahmed, is the eighth daughter of man without an heir. Raised as a boy, Ahmed eventually realizes she is a girl, but accustomed to her status of power as a male in Islamic society, decides to remain a man, even marrying her distant cousin Fatima. Her desire to have children marks the beginning of her sexual evolution. As a woman named Zahra, Ahmed discovers her true sexuality and her true identity. The sequel, The Sacred Night, completes Zahra’s transformation, with Zahra finding her life with a blind man named Consul.

Works

Novels

- Ben Jelloun, Tahar. L’Ecrivain Public. Paris: Seuil, 1983.

- —. L’Enfant de Sable. Paris: Seuil, 1985. Translated by Alan Sheridan as The Sand Child. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1987.

- —. Harrouda. Paris: Denoel, 1973.

- —. Jour de Silence a Tanger. Paris: Seuil, 1990. Translated Silent Day in Tangier. London: Quartet, 1991.

- —. Moha le Fou, Moha le Sage. Paris:Seuil, 1978.

- —. Muha al-ma`twah, Muha al-hakin. Paris: Seuil, 1982.

- —. La Nuit Sacree. Paris: Seuil, 1987. Translated by Alan Sheridan as The Sacred Night. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989.

- —. La Priere de l’Absent. Paris: Seuil, 1981.

- —. La Reclusion Solitaire. Paris: Denoel, 1976. Translated by Nick Hindley as Solitaire. London: Quartet, 1988.

- —. Les Yeux Baisses. Paris: Seuil, 1991. Translated by David Lobdell as With Downcast Eyes. London: Quartet, 1993.

- —. Corruption. Carol Volk (Translator). New York: The New Press, 1995.

- —. L’Auberge des pauvres. Paris: Seuil, 1997.

- —. Racism Explained to My Daughter. New York: The New Press, 1998.

- —. This Blinding Absence of Light. New York: The New Press, 2001.

- —. Islam Explained. New York: The New Press, 2002.

- —. La Belle au bois dormant. Paris: Seuil, 2004.

- —. The last friend. New York: The New Press, 2006.

- —. Yemma. Berlin: Berliner Taschenbuch Verl, 2007.

- —. Leaving Tangier. Translated by Linda Coverdale. New York: Penguin, 2009.

- —. The Rising of the Ashes. Translated by Cullen Goldblatt. San Francisco: City Lights, 2009.

- —. A Palace in the Old Village. New York: Penguin, 2010.

- —. Par Le Feu. Paris: Gallimard, 2011.

Poetry

- Ben Jelloun, Tahar. A L’Insu du Souvenir. F. Maspero, 1980.

- —. Les Amandiers Sont Morts de Leurs Blessures. F. Maspero, 1976.

- —. Le Discours du Chameau. F. Maspero, 1974.

- —. Hommes Sous Linceul de Silence. Atlantes, 1970.

- —. La Memoire Future: Anthologie de la Nouvelle Poesie du Maroc. F. Maspero, 1976.

- —. La Remontee des Cendres. Seuil, 1991.

- —. Sahara. Mulhouse, 1987.

Plays

- Ben Jelloun, Tahar. Chronique d’une Solitude. Avignon, France, 1976.

- —. Entretien avec Monsieur Said Hammadi, Ouvrier Algerien. Theatre National de Chaillot , 1982.

- —. La Fiancee de l’Eau. Theatre Populaire de Lorraine, 1984.

Nonfiction

- Ben Jelloun, Tahar. Giacometti. Grandvilliers: Editions Flohic, 1991.

- —. Haut Atlas: L’Exil de Pierres. Paris: Chene, 1982.

- —. Hospitalite Francaise: Racisme et Immigration, Maghrebine. New York: Seuil, 1984.

- —. Marseille, Comme un Matin d’Insomnie. Marseilles: Le Temps Parallele, 1986.

- —. Le Pain Nu. Translated from Arabic by Mohamed Choukri. Paris: F.Maspero, 1980.

- —. La Plus Haute des Solitudes: Misere Sexuelle d’Emigres Nord-Africains. New York: Seuil, 1977.

- —. L’Ablation. Paris: Gallimard, 2014.

Awards

- Prix de l’Amitie Franco-Arabe 1976 for Les Amandiers Sont Morts de Leurs Blessures

- Prix de l’Association des Bibliothecaires de France et de Radio Monte-Carlo 1978 for Moha le Fou, Moha le Sage

- Chevalier des Arts et des Lettres 1983 Prix Goncourt 1987 for La Nuit Sacree

- Chevailer de la Legion d’Honneur 1988 Prix des Hemispheres 1991 for Les Yeux Baisses

Works Cited

- Colby, Vineta, ed. World Authors 1985-90. New York: H.W. Wilson, 1995.

- DiYanni, Robert, ed. The Reader’s Adviser. 14th edition Volume 2: The Best in World Literature. New York: R.R. Bowker, 1994.

- France, Peter, ed. The New Oxford Companion to Literature in French. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Peacock, Scot, ed. Contemporary Authors. Volume 162. Detroit: Gale, 1998.

Author: Amy Owen, Spring 1999 Last edited: May 2017

1 Comment

Pingback: Project #3: Literature Engagement Project (In Progress) – Mindful Adventures