Basquiat and Postcoloniality

On Basquiat, art critic Robert Farris Thompson writes, “What identifies Jean-Michel Basquiat as a major artist is courage and full powers of self-transformation. That courage, meaning not being afraid to fail, transforms paralyzingly self-conscious’predicaments of culture’ into confident ‘ecstasies of cultures recombined.’ He had the guts, what is more, to confront New York art challenge number one: can you transform self and heritage into something new and named?” (36)

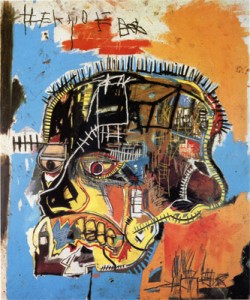

Very little criticism has been done examining the work produced by Jean-Michel Basquiat. While his place in the history of American art is still under dispute, it cannot be denied that during the eight years that he painted, much of his work examines the legacy of the colonial enterprise and his relationship to that legacy (See Postcolonial Performance and Installation Art). Whether recasting the work of European masters like Leonardo Da Vinci in his own terms or recounting events from Haitian, Puerto Rican, African, and African American history, Basquiat presented a vision of a fragmented, colonized self in search of an organizing principle (See Mimicry, Ambivalence, and Hybridity). Now, ten years after his death, critics can revisit his work apart from the taint of the market-driven art boom of the 1980s. Perhaps the tools developed in the field of postcolonial studies will help to unlock some of the mysteries contained in the work of this fascinating and complex artist. Three of his works that rather overtly examine issues of colonialism and the position of the post-colonial subject are reproduced below.

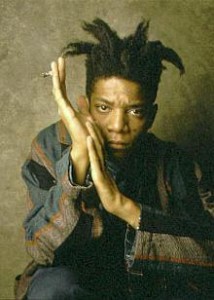

Biography

Jean-Michel Basquiat was born on December 22, 1960 in Brooklyn, New York. His father, Gerard Basquiat was born in Port-au-Prince, Haiti and his mother, Matilde, was born in Brooklyn to Puerto Rican parents. Early on, Basquiat displayed a proficiency in art which was encouraged by his mother. In 1977, Basquiat, along with friend Al Diaz begins spray painting cryptic aphorisms on subway trains and around lower Manhattan and signing them with the name SAMO© (Same Old Shit). Some of these include: “SAMO© as an end to mind-wash religion, nowhere politics, and bogus philosophy,” “SAMO© saves idiots,” and “Plush-safe he think; SAMO© .”

In 1978 Basquiat left home for good and quit high school just one year before graduating. He lived with friends and began selling hand painted postcards and T-shirts. In June of 1980, Basquiat’s art was publicly exhibited for the first time in a show sponsored by Colab (Collaborative Projects Incorporated) along with the work of Jenny Holzer, Lee Quinones, Kenny Scharf, Kiki Smith, Robin Winters, John Ahearn, Jane Dickson, Mike Glier, Mimi Gross, and David Hammons. Basquiat continued to exhibit his work around New York City and in Europe, participating in shows along with the likes of Keith Haring and Barbara Kruger.

In December of 1981, poet and artist Rene Ricard published the first major article on Basquiat entitled “The Radiant Child” in Art Forum. In 1982, Basquiat was featured in the group show “Transavanguardia: Italia/America” along with neo-expressionists Sandro Chia, Francesco Clemente, Enzu Cucchi, David Deutsch, David Salle, and Julian Schnabel (who will go on to direct the biographical film Basquiat in 1996). In 1983 Basquiat had one-artist exhibitions at the galleries of Annina Nosei and Larry Gagosian and was also included in the “1983 Biennial Exhibition” at the Whitney Museum of American Art. It was also in 1983 that Basquiat was befriended by Andy Warhol, a relationship which sparked discussion concerning white patronization of black art, a conflict which remains, to this day, at the center of most discussions of Basquiat’s life and work. Basquiat and Warhol collaborated on a number of paintings, none of which are critically acclaimed. Their relationship continued, despite this, until Warhol’s death in 1987.

By 1984, many of Basquiat’s friends had become quite concerned about his excessive drug use, often finding him unkempt and in a state of paranoia. Basquiat’s paranoia was also fueled by the very real threat of people stealing work from his apartment and of art dealers taking unfinished work from his studio. On February 10, 1985, Basquiat appeared on the cover of The New York Times Magazine, posing for the Cathleen McGuigan article “New Art, New Money: The Marketing of an American Artist.” In March, Basquiat had his second one-artist show at the Mary Boone Gallery. In the exhibition catalogue, Robert Farris Thompson spoke of Basquiat’s work in terms of an Afro-Atlantic tradition, a context in which this art had never been discussed (see Paul Gilroy: The Black Atlantic).

In 1986, Basquiat travelled to Africa for the first time where his work was shown in Abidjan, Ivory Coast. In November, a large exhibition of more than sixty paintings and drawings opened at the Kestner-Gesellschaft in Hanover, Germany; at twenty-five Basquiat was the youngest artist ever given an exhibition there. In 1988, Basquiat had shows in both Paris and New York; the New York show was praised by some critics, an encouraging development.

Basquiat attempted to kick his heroin addiction by leaving the temptations of New York for his ranch in Hawaii. He returned to New York in June 1988 claiming to be drug-free. On August 12, 1988 Basquiat died as the result of a heroin overdose. He was 27.

Primary source for biography:

Sirmans, M. Franklin. “Chronology.” Jean-Michel Basquiat. Ed. Richard Marshall. New York: Whitney/Abrams, 1992. 233-250.

Works Cited

- Arnault, Martine. “Basquiat, from Brooklyn.” Cimaise 36 (Nov./Dec. ’89): 41-4.

- Bevan, Roger. “Just How Good was Jean-Michel Basquiat?” Art Newspaper 7 (Mar. ’96): 9.

- Castle, Frederick Ted. “Saint Jean Michel.” Arts Magazine 63 (Feb. ’89): 60-1.

- Couturier, Elisabeth. “Basquiat Superstar.” Beaux Arts Magazine 145 (May ’96): 88-93.

- Davvetas, Demosthenes. “Lines, Chapters, and Verses: the Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Art forum 25 (Apr. ’87): 116-20.

- Decker, Andrew. ” The Price of Fame: the Turbulent Life and Art of Jean Michel Basquiat.” Art News 88 (Jan. ’89): 96-101.

- Galligan, Gregory. “More Post-modern than Primitive.” Art International No 5 (Winter 88): 59-60, 62.

- Hayt, Elizabeth. “Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Art News 96 (Jan. ’97): 114.

- Hebdige, Dick. “Welcome to the Terrordome: Jean-Michel Basquiat and the “Dark” Side of Hybridity.” Jean-Michel Basquiat. Ed. Richard Marshall. New York: Whitney/Abrams, 1992. 60-70.

- Hooks, Bell. “Altars of Sacrifice: Re-membering Basquiat.” Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations. London: Routledge, 1994. 25-37.

- Lucie-Smith, Edward. “The Writing on the Wall.” Art Review 48 (Mar. ’96): 20-2.

- Madoff, Steven Henry. “What is Postmodern About Painting: the Scandinavia Lectures.” Arts Magazine. 60 (Oct. ’85): 59-64.

- Marshall, Richard, editor. Jean-Michel Basquiat. New York: Whitney/Abrams,1992.

- —. “Repelling Ghosts.” Jean-Michel Basquiat. New York: Whitney/Abrams, 1992. 15-27.

- McEvilley, Thomas. “Royal Slumming: Jean-Michel Basquiat Here Below.” Art forum 31 (Nov.’92): 92-7.

- O’Grady, Lorraine. “A Day at the Races.” Art forum 31 (Apr. ’93): 10-12.

- Ricard, Rene. “The Radiant Child.” Art forum 24 (Dec.1981): 35-43.

- Shonibare, Yinka. “Jean-Michel Basquiat, Please Do Not Turn in Your Grave, It’s Only TENO.” Third Text No28/29 (Autumn/Winter’94): 199-202.

- Stamets, Bill. “A Cautionary Tale: Memorializing Basquiat.” New Art Examiner 23 (Nov. ’96): 19.

- Tate, Greg, “Black like B.” Jean-Michel Basquiat. Ed. Richard Marshall. New York: Whitney/Abrams, 1992. 56-59.

- Thompson, Robert Farris. “Royalty, Heroism, and the Streets: The Art of Jean-Michel Basquiat.” Jean-Michel Basquiat. Ed.Richard Marshall. New York: Whitney/Abrams, 1992. 28-43.

Author: Kimberley Parker, Spring 1998

Last edited: May 2017

1 Comment

“Three of his works that rather overtly examine issues of colonialism and the position of the post-colonial subject are reproduced below.”

Hello! Can you tell me where can I find those works images at your post?