This article discusses contemporary performance and installation artists who address the objectification of the non-white bodies in Western culture: Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gomez-Peña, Joyce Scott and Kay Lawal, James Luna, Renée Green, Lyle Ashton Harris and Renée Cox, and Grace Jones. Significantly, many of these performance artists use their own bodies as a medium to interrogate the history of “human exhibitionism” in Europe and the United States. By exhibiting their own bodies these artists use performance art to explore the complex ways in which the displays of the non-white body have affected and continue to feed popular stereotypes about people of color in the Western imagination. The performances assert that racial and cultural difference and “otherness” in Western society are inscribed on the non-white body (see Orientalism). By recalling specific histories of human display, the artists implore their audiences to recognize, reexamine, and transcend their intolerance and prejudice against persons who appear visibly different from themselves (See essentialism).

This page introduces a small, representative sample of artists who have engaged this theme and it serves as an introduction to this genre of performance art. By way of organization, each of the links below take viewers to one performance piece from one of the above mentioned. After an image and a brief discussion, a statement from the artist reflecting on their work follows, and each section concludes with a short bibliography of further reading sources.

Coco Fusco and Guillermo Gomez-Peña. Undiscovered Amerindians, 1992.

[pl_video type=”youtube” id=”gLX2Lk2tdcw”]In order to address the widespread practice of human displays, Fuscoand Gomez-Peña enclosed their own bodies in a ten-by-twelve-foot cage and presented themselves as two previously unknown “specimens representative of the Guatinaui people” in the performance piece “Undiscovered Amerindians.” Inside the cage Fusco and Peña outfitted themselves in outrageous costumes and preoccupied themselves with performing equally outlandish “native” tasks. Gomez-Peña was dressed in an Aztec style breastplate, complete with a leopard skin face wrestler’s mask. Fusco, in some of her performances, donned a grass skirt, leopard skin bra, baseball cap, and sneakers. She also braided her hair, a readily identifiable sign of “native authenticity.”

In a similar fashion to the live human spectacles of the past, Fusco and Gomez-Peña performed the role of cultural “other” for their museum audiences. While on display the artists’ “traditional” daily rituals ranged from sewing voodoo dolls, to lifting weights to watching television to working on laptop computers. During feeding time museum guards passed bananas to the artists and when the couple needed to use the bathroom they were escorted from their cage on leashes. For a small donation, Fusco could be persuaded to dance (to rap music) or both performers would pose for Polaroids. Signs assured the visitors that the Guatinauis “were a jovial and playful race, with a genuine affection for the debris of Western industrialized popular culture … Both of the Guatinauis are quite affectionate in the cage, seemingly uninhibited in their physical and sexual habits despite the presence of an audience.” Two museum guards from local institutions stood by the cage and supplied the inquisitive visitor with additional (equally fictitious) information about the couple. An encyclopedic-looking map of the Gulf of Mexico, for instance, showed the supposed geographic location of their island. Using maps, guides, and the ambiguous museum jargon, Fusco and Gomez-Peña employed the common vocabulary of the museum world to stage their own display.

Despite Fusco and Gomez-Peña’s professed intentions that Undiscovered Amerindians should be perceived as a satirical commentary, more than half of the visitors to the museums who came upon the performance believed that the fictitious Guatinaui identities were real.

In 1992, Fusco and Gomez-Peña first staged the performance on Columbus Plaza, Madrid, Spain, as a part of the event Edge ’92 Biennial, organized in commemoration of the quincentennial of Columbus’ voyage to the New World. The performance piece had an illustrious two year exhibition history including performances at Covent Garden in London, The National Museum of Natural History at the Smithsonian in Washington D.C., The Field Museum in Chicago, the Whitney Museum’s Biennial in New York, the Australian Museum of Natural History and finally in Argentina, on the invitation of the Fundacion Banco Patricios in Buenos Aires.

Quote about Undiscovered Amerindians from Coco Fusco:

According to Fusco, she and Gomez-Peña aimed to conduct a “reverse ethnography … Our cage became a blank screen onto which audiences projected their fantasies of who and what we are. As we assumed the stereotypical role of the domesticated savage, many audience members felt entitled to assume the role of colonizer, only to find themselves uncomfortable with the implications of the game” (Fusco 47).

Bibliography

- Fusco, CoCo. English is Broken Here. New York: The New Press, 1995.

- Guillermo, Gomez-Peña. The New World Border. San Francisco: City Lights, 1996.

- A site maintained by Gomez-Peña: http://zonezero.com/magazine/articles/gomezpena/gomezpena.html

The Spectacle of the Hottentot Venus: The Thunder Thigh Revue’s Women of Substance

[pl_video type=”youtube” id=”SKPWPINbypg”]In 1986 artist Joyce Scott in collaboration with actress and comedian Kay Lawal formed the two-person performance troupe, The Thunder Thigh Revue. As the name of their performance partnership reveals, the two women in the Revue directly engaged issues surrounding the representation and perception of the body, and more specifically the black female body in American society. The first performance the Thunder Thigh Revue produced was called Women of Substance in which the tradition of exhibiting the non-white body in public spectacles was central.

At the moment of Women of Substance, which both the reviewers and Joyce Scott conceive as the pinnacle of the performance, Scott appears in the guise of Saarjite Baartman. The lights in the performance space dim, sobering the atmosphere of the room. Scott walks slowly to the center of the stage wearing an extension on her buttocks made out of sponge. Only a sheer stocking covers the rest of her body. Scott, illuminated by a bright white spotlight, stares blindly out at the audience and begins a mournful cry.

In what sounds like a low-pitched wail, Scott as Baartman speaks to the audience. She laments being far away from home in South Africa, and discusses her infinite loneliness since she was brought to “new shores.” In her portrayal of Baartman, Scott tells of the violation and humiliation of her body as an object of public display. She also speaks of her influence in the popular culture of Europe in the nineteenth century, such as how a popular women’s fashion device’s like the bustle, a padded butt extension, was inspired by her. Although oft-times in Scott’s monologue as Saarjite her individual words are difficult to discern, the overall drone of the wail itself conveys the sadness and pain of being on public display and the subject of ridicule. Through her song Scott gives Baartman a voice, imploring her audience to get past the spectacle of the body to perceive Baartman as a human being with feelings, desire, and subjectivity.

Baartman is part of the cast of characters that Scott and Lawal employ to express “the pain and passion of being the ‘other,’ an overweight black woman in this society”(Stokes Sims 221 ). As Lowery Stokes Sims notes in “Aspects of Performance in the Work of Black American Women,” throughout the performance, “Apparitions of women of substance float in and out of the performance giving testimony to their rage, their indignation, and their pride and determination” (Stokes Sims 219). In the scene that precedes the Hottentot Venus performance, Scott appears as Venus from Botticelli’s famous painting, outfitted in sponge replicas of Venus’ shell and flowing dirty-blond hair, whom she describes as the quintessential personification of beauty in Western art. By performing the two vignettes together, by introducing the audience to these two Venuses, Scott also highlights the vast discrepancies between the Western beauty ideal epitomized in Botticelli’s Venus and the condemnation of the black female body in Western culture. While the latter becomes the celebrated subject of Western painting, the former’s body is fetishized in public freak shows. Other characters include a black Statue of Liberty and a dialogue with a refrigerator. All the women of substance in the performance encourage their audience to examine the stereotypes people hold based on physical appearance. In the United States, the Thunder Thigh Revue appeared primarily in art museums and galleries, including The Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland Art Institute, and Sushi Gallery, San Diego. The pair also made numerous theater appearances.They staged Women of Substance at the Edinburgh festival in Scotland.

Quote from Joyce Scott on Women of Substance:

In an interview I conducted with Scott she said her aim in performance art is to seize “gross stereotypes and fuck with them.” She explains,”There’s a cesspool of stereotypes about looks, and I’m trying to put a new spin it …” Scott recognizes that that her own physical appearance which she described as “a fat black woman with gappy teeth and wild hair,” is reminiscent of “the stereotype that African-Americans have tried to debunk since the 1960s!” (Searle 48). Her own personal experience and awareness of how people visually perceive her, is a major impetus behind her investigation through performance of the ways people in society visually appraise, evaluate, and make stereotypic assumptions regarding “others” based on physical appearance.

See also Representation.

Bibliography

- Hammond, Leslie King, and Lowery Stokes-Sims. Art as A Verb: The Evolving Continuum, Installations, Performances, and Videos. Baltimore: Maryland Institute College of Art, 1988.

- Searle, Karen. “Joyce Scott: Migrant Worker for the Arts.” Ornament 15.4 (1992) :46-51.

- Sims, Lowery Stokes. “Aspects of Performance in the Work of Black American Women Artists.” Feminist Art Criticism: An Anthology. Ed. Arlene Raven and Cassandra Langer. London: U.M.I Research Press,

- 1988. 207-225.

James Luna: Artifact Piece

James Luna often uses his body as a means to critique the objectification of Native American cultures in Western museum and cultural displays. He dramatically calls attention to the exhibition of Native American peoples and Native American cultural objects in his Artifact Piece, 1985-87. For the performance piece Luna donned a loincloth and lay motionless on a bed of sand in a glass museum exhibition case. Luna remained on exhibit for several days, among the Kumeyaay exhibits at the Museum of Man in San Diego. Labels surrounding the artist’s body identified his name and commented on the scars on his body, attributing them to “excessive drinking.” Two other cases in the exhibition contained Luna’s personal documents and ceremonial items from the Luiseño reservation.

Many museum visitors as they approached the “exhibit” were stunned to discover that the encased body was alive and even listening and watching the museum goers. In this way the voyeuristic gaze of the viewer was returned, redirecting the power relationship.

Through the performance piece Luna also called attention to a tendency in Western museum displays to present Native American cultures as extinct cultural forms. Viewers who happened upon Luna’s exhibition expecting a museum presentation of native American cultures as “dead,” were shocked by the living, breathing, “undead” presence of the luiseño artist in the display. Luna in Artifact Piece places his body as the object of display in order to disrupt the modes of representation in museum exhibitions of native others and to claim subjectivity for the silenced voices eclipsed in these displays.

Artifact Piece was first staged in 1987 at the Museum and Man, San Diego. Luna also performed the piece for The Decade Show, 1990, in New York.

Quote from Luna:

The Artifact Piece, 1987, was a performance/installation that questioned American Indian presentation in museums-presentation that furthered stereotype, denied contemporary society and one that did not enable an Indian viewpoint. The exhibit, through ‘contemporary artifacts’ of a Luiseño man, showed the similarities and differences in the cultures we live, and putting myself on view brought new meaning to “artifact.” (Durland 37)

Suggested Reading

- Durland, Steven. “Call Me in ’93: An Interview with James Luna.” High Performance (Winter 1991) 34-39.

- Fisher, Jean. “In Search of the ‘Inauthentic’: Disturbing Signs in Contemporary Native American Art.” Art Journal (Fall 1992) 44-50.

- Luna, James. “Allow Me to Introduce Myself.” Canadian Theatre Review 68 (Fall 1991) 46-47.

Renée Green: Revue 1990

In the mixed media installation Revue, installation artist Renée Green combined several visual images and texts pertaining to the black female body: a small diminutive representation of the Hottentot Venus is centrally placed in the installation, surrounded by a series of photographically manipulated images of Josephine Baker. Framing these images on both sides run a row of texts, some of which quote Josephine Baker’s critics and others excerpts from 19th century travel accounts. The installation also includes a small open cabinet on which a toy circus comprising several miniaturized animal representations is placed. On the floor in front of the installation another wind-up animal, a lion, is caged in its surroundings. The wind-up toy has been viewed by critics as stand in for “The Hottentot Venus,” who was similarly caged and performed the part of an animal.

In the installation, Green deals with visual representations of the black female body, like the Hottentot Venus and Josephine Baker, which were prominently positioned at the center of Britain and France’s popular exoticized gaze. Interestingly, Green’s manipulation of the scale of the images, particularly of the small Hottentot Venus image, and the blurred focus of the Baker photographs precisely resists visual apprehension.

Green also concentrations on the fascination with the black female body as manifest discursively in nineteenth century travel literature and in critiques of Baker’s performances. In contrast to the visual images the texts are blown up larger than life. One of the enlarged panels of the excerpts from a travel account reads: “The dance of the Negresses is incredibly indecent … she gets into positions so lascivious, so lubricious that it’s impossible to describe them … It’s true that the Negresses don’t appear to have the depraved intentions which one would imagine; it’s a very old custom, which continues innocently in this country; so much so that one sees children of six performing this dance, certainly without knowing what they’re leading up to.” The visual and discursive mediations on the black female both in the metropoles of Britain and France and in distant countries, as recorded by a traveler, are juxtaposed in the installation.

Revue was installed as part an exhibition The Body as Measure at the Davis Museum and Cultural Center, Wellesley College in 1994. Revue was reinstalled for the exhibition Mirage: Enigmas of Race, Difference, and Desire in London in 1995.

Quote from Green:

In particular I was interested in the way that an artist (filmmaker) and writer such as Laura Mulvey was trying to rethink the way in which certain ideas about visual pleasure were developed. I was also trying to figure out the way in which a body could be visualized, especially a black female body, yet address the complexity of reading that presence without relinquishing pleasure and history. (Read 146 )

Further Reading

- Fox, Judith Hoos. The Body as Measure. Wellesley College: Davis Museum and Cultural Center, 1994.

- Alan Read. The Fact of Blackness. Seattle and London: Bay Press and inIVA, 1996.

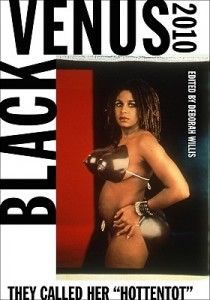

Lyle Ashton Harris and Renee Valerie Cox: “Hottentot Venus 2000″

For the exhibition Mirage: Enigmas of Race, Difference and Desire (1995), Lyle Ashton Harris in collaboration with Renee Valerie Cox created the photograph, “Venus Hottentot 2000.” In this futuristic reinterpretation of the Hottentot Venus, Renee Valerie Cox directly inserts her own body into the historical matrix of Western representations that configured black female sexuality. In the photograph Cox’s body is transformed, recalling the Hottentot Venus, with the addition of protruding metallic breasts and an accompanying metal butt extension. The white strings that delicately hold these metallic body parts in place with bow, seem to emphasize the artists’ complex and ambivalent relationships to representations of black female sexuality. Cox wears the metallic appendages like a costume or disguise, but her own nude body is simultaneously revealed to the viewer. She stands in profile emphasizing her bodily dimensions, hands akimbo, and stares directly at the viewer.

“Hottentot 2000″ is one photograph in a series by Harris called The Good Life, 1994.

Quote from Harris:

This reclaiming of the image of the Hottentot Venus is a way of exploring my own psychic identification with the image at the level of spectacle. I am playing with what it means to be an African diasporic artist producing and selling work in a culture that is by and large narcissistically mired in the debasement and objectification of blackness. And yet, I see my work less as a didactic critique and more as an interrogation of the ambivalence around the body. (Read 150)

Bibliography

- Mirage: Enigmas of Race, Difference and Desire. London: ICA and inIVA, 1995.

- Alan Read. The Fact of Blackness. Seattle and London: Bay Press and inIVA, 1996.

Grace Jones: 1985 Performance in Paradise Garage

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Grace Jones boldly interrogated both racial and sexual stereotypes associated with the black female body, through her work in performance. Interestingly, Jones, a Jamaican born artist, was actively working in the Parisian fashion world as a model at the time she moved into performance art. Her involvement and popularity in the Parisian fashion world as a spectacle, being a model, may be compared with the likes of Josephine Baker and Saarjite Baartman before her, black females whose bodies became the locus of the Parisian imagination.

Jones’ bold and often confrontational dress and performance style played with and disrupted primitivist myths about black sexuality. In collaboration with artists like Jean-Paul Goude and Keith Haring, Jones transformed her body into medley characters, many of which satirized a primitivist reading of the black female body. The multiple personas of Grace Jones ranged widely from overly sexualized dance performances in which she donned a gorilla or tiger suit to very masculinized self-representations. For these performances Jones would appear with a crew cut in a tailored men’s suit. Both these modes of representation in Jones’ work, as hyper-sexualized animal and instances of cross-dressing have been related to Josephine Baker’s performances, more specifically, her “jungle” performances in banana and tusk skirts and the famous photographs of Baker in a top hat and tuxedo (Kershaw 21).

In 1985 Jones collaborated with Keith Haring in a performance staged at Paradise Garage, an alternative dance club in New York City. For the performance Haring painted Jones’ body in characteristically Haring-stylized white designs. Interestingly, Haring’s body art was inspired by the body paintings of the African Masai. Jones also adorned her body with an elaborate sculptural assemblage of pieces of rubber, plastic sheen, and metal, created by Haring and David Spada. A towering sculptural headdress topped off the costume. Her breasts were delineated with protruding metal coils. The metal coils were a deliberate reference to an iron-wire sculpture of Josephine Baker by artist Alexander Calder. Later in the performance Jones appeared in a Baker-style skirt, composed of yellow neon spikes. Through the painting, adornment, and importantly through her performance, Jones played with iconic signs of “the primitive,” and transformed these signifiers and her body into a site of power.

Bibliography

- Kershaw, Miriam. “Postcolonialism and Androgyny: The Performance Art of Grace Jones.” Art Journal 56 (Winter 1997): 19-25.

- Wallace, Michelle. “Modernism, Postmodern and the Problem of the Visual in Afro-American Culture.” Out There: Marginalization and Contemporary Culture. Ed. Russell Ferguson. 39-50.

See Also Gender and Nation, Third World and Third World Women, Hybridity and Postcolonial Music, Field Day Theatre, Derek Walcott

Author: Krista A. Thompson, Spring 1998

Last edited: November 2017

1 Comment

Pingback: Postcolonial Thoughts: Lyle Ashton Harris Lecture at the HIGH: Indecisive moments | Creative Thresholds