The knife cut down the guardian of the village today.

Now he is dead and gone.

Before the village was dirty,

But now without the guardian it is clean.

So look at us, we are only women and the men have come to

beat the tam-tam.

They have phalli like the elephants.

They have come when we are bleeding.

Now back to the village where a thick Phallus is waiting.

Now we can make love because our sex is clean (Lightfoot-Klein, 71).

These lyrics, sung by Kenyan girls after undergoing the process of genital cutting, provides a startling insight into the process. It is a process steeped in religion and custom in many countries. Female genital cutting (referred to as female genital circumcision in some sects) is a rite of passage from childhood to womanhood practiced by numerous cultures. It consists primarily of the cutting the clitoris and/or other major sexual organs (such as the labia minora and majora.) Its severity and type depends on the region and the culturally dominant practice of an area (Kosso-Thomas, 15). Commonly performed on girls from age four to fourteen, it is done as early as age two in some areas. There are four major types of female genital cutting (FGC): circumcision proper (Sunna), excision, infibulation, and introcision (WHO, 4).

Types of FGC

- Circumcision Proper

This particular form of FGC (referred to as Sunna circumcision in Muslim countries) involves the removal of the prepuce, or “hood” of the clitoris (WHO, 4). The body of the clitoris, however, remains intact (Walker, 367). Sunna is performed under the teachings of the prophet Muhammad, and is done primarily in Sudan (Lightfoot-Klein, 5). An Arab word meaning “tradition,” Sunna is highly linked to both custom and religion (Lightfoot-Klein, 33) (see Women, Islam and the Hijab).

- Excision

This form, involving the removal of the clitoris itself as well as the labia minora, is one of the severest forms of FGC (WHO, 4).

- Infibulation

Referred to as Pharonic circumcision in most Muslim countries, infibulation involves the removal of the clitoris, labia minora, and fleshy layers of the labia majora. This is the severest form of FGC and perhaps the most painful. The excisor holds the clitoris between the thumb and the index finger, amputating it with a sharp object, either a knife or sharpened rock. Although there is excessive bleeding in the process, it is partially stopped by packing the wound with gauze. The wound is then fused together with thorns to help with healing (WHO, 7). However, a small opening is left to allow for urine and menstrual flow passage (Walker, 367).

- Introcision

Introcision is the cutting into the vagina either digitally or by means of a sharp instrument (WHO, 4). Overall, it is the enlargement of the vaginal orifices by means of tearing it downward and is most common in Somalia (Lightfoot-Klein, 33).

Reasons for FGC

The origins of FGC are obscure, yet they are believed to date back to antiquity, as far back as the 5th century B.C in Egypt (Lightfoot-Klein, 27). The current reasons for performing FGC are numerous. For most, FGC is believed to maintain cleanliness of the female sexual organs, decreasing vaginal secretions contaminate the female body (Koso-Thomas, 8). Since sexual intercourse after FGC involves considerable pain, it is believed to prevent promiscuity and preserve the virginity of the excised (Koso-Thomas, 9). It is also believed to “abolish sexual desire in women,” often serving as a means of contraception in some areas (Lightfoot-Klein, 23). Although the belief is not scientifically based, many also argue that the process maintains good health, with the excised suffering from considerably less disease than uncircumcised women (Thomas, 8). In some extreme cases, it is thought that the clitoris is poisonous and will kill a man if he comes in contact with it during intercourse (Epebolin and Epebolin, qtd. in Lightfoot-Klein, 38). Thus, in order to maintain the man’s life and the woman’s purity, the clitoris is excised.

Complications due to the process

There are many immediate and long-term complications associated with the multiple forms of FGC. There are large instances of urinary infections due to unsterile equipment and urine retention due to the excessively small openings left (Thomas, 25).

Septicaemia, or blood poisoning is also common due to these unhygenical equipment as well as haemorrhage of major blood vessels (Thomas, 25). In severe cases, the procedure has also resulted in death. As far as the long term, there is often abscess formation when the embedded stitch fails to be absorbed. The result can be a raised, painful scar, or a cyst which interrupts menstrual flow and makes childbirth doubly painful (WHO, 27). The spread of HIV/AIDS is also associated with FGC due to excessive blood loss and unsanitary equipment (WHO, 28). Yet, the most devastating effect of the process is perhaps the psychological damage endured by the women. Many complain of trauma from the procedure: recurrent nightmares, as well as decreased sexual orgasm during intercourse (WHO, 33). For many, the sexual act becomes so painful that it results in severe depression. The wedding night usually starts the cycle of pain. The husband, due to the excessively small hole, must use a knife to loosen the stitches enough to allow for penetration. Similar to the initial ritual of FGM, this involves excessive bleeding. However, the women are submissive to their husbands in fear of hurting his feelings or dishonoring him, suffering the pain for numerous years (Lightfoot-Klein, 11).

Where is FGC practiced?

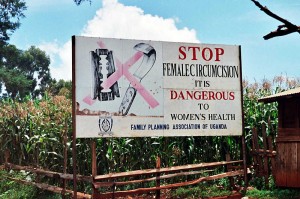

Contrary to popular belief, FGC is not only performed in the remotest depths of Africa. As an indication of cultural awareness, it is performed in higher social classes as well as the lower, “peasant class” (Lightfoot-Klein, 47). In Asia, Muslims of the Philippines and Malaysia still practice varied forms of FGM (Thomas, 17). Within Europe, France and Germany there is an uncommon number of excised women due to African and Asian immigrants that have settled in this area (Thomas, 17). In Egypt, Somalia, and Sudan the procedure is used to stop extramarital affairs due to the excessive pain associated with intercourse (WHO, 2). In Kenya, Uganda, and West African countries such as Sierra Leone, a girl has a child out of wedlock to prove her fertility and then undergoes circumcision shortly before marriage (WHO, 2). Within Africa, the process occurs within a triangular band across the continent: Ethiopia and the Horn of Africa. In Ethiopia, it is concentrated with the Ibo, Hausa, and Yoruba people,with infibulation occurring primarily in the Horn Of Africa (Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan) (Lightfoot-Klein, 31).

Attitudes towards FGC

As with all topics, there are differing views on the subject of FGC. Westerners outside of the traditions argue that it is on the same level as torture, with the effects lasting far after the actual ritual is performed. Since older women perform the ritual on the young girls, it is viewed as women perpetuating violence from one generation to the next. In her book, “Warrior Marks” (a transcript of the movie of the same name), Alice Walker points to the excessive mental anguish endured by the survivors of FGC. Interviewing both the excisor and the excised, Walker provides both sides of the issue. While realizing the painful effects of the process, many undergo FGC in order to respect the customs and religion of their nation. Those in favor of continuing FGC often point to the reasons previously listed: maintenance of cleanliness, deterring promiscuity, and increasing healthiness. As long as the process is performed, there will be controversy associated (Walker, Lightfoot-Klein, WHO).

See also Nawal El Saadawi, Third World and Third World Women.

Selected Bibliography

Literature and Film Dealing with Female Genital Cutting

- Abusharaf, Rogaia Mustafa. Female Circumcision: Multicultural Perspectives. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

- Gruenbaum, Ellen. The Female Circumcision Controversy: An Anthropological Perspective. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001.

- Lazreg, Marnia. The Eloquence of Silence: Algerian Women in Question. New York: Routledge, 1994.

- Morgan Robin, and Gloria Steinem. The International Crime of Genital Mutilation. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1983.

- Parmar, Pratibha. “Warrior Marks.” Our Daughters Have Mothers Inc.,1993.

- Robertson, Claire. “Grassroots in Kenya: Women, Genital Mutilation and Collective Action, 1920-1990.” Signs 21.31 (1996): 615-642.

- Walker, Alice. Possessing the Secret of Joy. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1992.

Works Cited

- Lightfoot-Klein. Prisoners of Ritual: An Odyssey into Female Genital Circumcision in Africa. New York: Harrington Park Press, 1996.

- Koso-Thomas, Olayinka. The Circumcision of Women: A Strategy for Eradication. New Jersey: The Bath Press, 1987.

- Walker, Alice, and Pratibha Parmar. Warrior Marks: Female Genital Mutilation and the Sexual Blinding of Women. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1993.

- Walley, Christine J. “Searching for Voices: Feminism, Anthropology,and the Global Debate over Female Genital Operations.” Cultural Anthropology 12.3 (1997): 405-438.

- World Health Organization. Female Genital Mutilation: an Overview. Geneva: WHO Graphics, 1998.

Related Web Sites

World Health Organization: fact sheet on female genital mutilation

http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/index.html

WomensHealth.GOV

http://www.womenshealth.gov/publications/our-publications/fact-sheet/female-genital-cutting.html

UNICEF

http://www.unicef.org/publications/index_29994.html

Author: Jeannelle Bryan, Fall 2000

Last edited: October 2017