“A moment comes, which comes but rarely in history, when we step out from the old to the new, when an age ends, and when the soul of a nation, long suppressed, finds utterance.”

– Jawarharal Nehru, “Tryst With Destiny” speech celebrating Indian independence

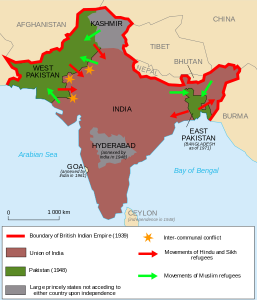

Whether the partition of these countries was wise and whether it was done too soon is still under debate. Even the imposition of an official boundary has not stopped conflict between them. Boundary issues, left unresolved by the British, have caused two wars and continuing strife between India and Pakistan. August 14, 1947 saw the birth of the new Islamic Republic of Pakistan. India won its freedom from colonial rule at midnight the next day, ending nearly 350 years of British presence in India. When the British left, they partitioned India, creating the separate countries of India and Pakistan to accommodate religious differences between Pakistan, which has a majority Muslim population, and India, which is primarily Hindu.

The partition of India and its freedom from colonial rule set a precedent for nations such as Israel, which demanded a separate homeland because of irreconcilable differences between the Arabs and the Jews. The British left Israel in May 1948, handing the question of division over to the UN. Unenforced UN Resolutions to map out boundaries between Israel and Palestine have led to several Arab-Israeli wars and the conflict still continues.

Reasons for Partition

By the end of the 19th century, several nationalist movements had emerged in India. Indian nationalism had expanded as the result of British policies of education and the advances made by the British in India in the fields of transportation and communication. However, British insensitivity to and distance from the people of India and their customs created such disillusionment among Indians that the end of British rule became necessary and inevitable. (See Sepoy Mutiny)

While the Indian National Congress was calling for Britain to quit India, in 1943 the Muslim League passed a resolution demanding the British divide and quit. There were several reasons for the birth of a separate Muslim homeland in the subcontinent, and all three parties — the British, the Congress, and the Muslim League — were responsible.

As colonizers, the British had followed a divide-and-rule policy in India. In the census they categorized people according to religion and viewed and treated them as separate from each other. The British based their knowledge of the people of India on religious texts and the intrinsic differences they found in them, instead of examining how people of different religions coexisted. They also were fearful of the potential threat from the Muslims, who were the former rulers of the subcontinent, ruling India for over 300 years under the Mughal Empire. To win them over to their side, the British helped establish the Mohammedan Anglo Oriental College at Aligarh and supported the All-India Muslim Conference, both of which were institutions from which leaders of the Muslim League and the ideology of Pakistan emerged. As soon as the league was formed, Muslims were placed on a separate electorate. Thus, the separateness of Muslims in India was built into the Indian electoral process.

There was also an ideological divide between the Muslims and the Hindus of India. While there were strong feelings of nationalism in India, by the late 19th century there were also communal conflicts and movements in the country that were based on religious identities rather than class or regional ones. Some people felt that the very nature of Islam called for a communal Muslim society. Added to this were the memories of power over the Indian subcontinent that the Muslims held, especially in old centers of Mughal rule. These memories might have made it exceptionally difficult for Muslims to accept the imposition of colonial power and culture. Many refused to learn English and to associate with the British. This was a severe drawback as Muslims found that cooperative Hindus found better government positions and thus felt that the British favored Hindus. Consequently, social reformer and educator Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, who founded Mohammedan Anglo Oriental College, taught the Muslims that education and cooperation with the British was vital for their survival in the society. However, tied to all the movements of the Muslim revival was the opposition to assimilation and submergence in Hindu society.

Hindu revivalists also deepened the chasm between the two nations. They resented the Muslims for their former rule over India. Hindu revivalists rallied for a ban on the slaughter of cows, a cheap source of meat for the Muslims. They also wanted to change the official script from the Persian to the Hindu Devanagri script, effectively making Hindi rather than Urdu the main candidate for the national language.

The Congress made several mistakes in their policies which further convinced the League that it was impossible to live in an undivided India after freedom from colonial rule because their interests would be completely suppressed. One such policy was the institution of “Bande Matram,” a national anthem historically linked to anti-Muslim sentiment, in the schools of India where Muslim children were forced to sing it.

The Congress banned support for the British during the Second World War while the Muslim League pledged its full support, which found favor from the British, who needed the help of the largely Muslim army. The Civil Disobedience Movement and the consequent withdrawal of the Congress party from politics also helped the league gain power, as they formed strong ministries in the provinces that had large Muslim populations. At the same time, the League actively campaigned to gain more support from the Muslims in India, especially under the guidance of dynamic leaders like Jinnah. There had been some hope of an undivided India, but the Congress’ rejection of the interim government set up under the Cabinet Mission Plan in 1942 convinced the leaders of the Muslim League that compromise was impossible and partition was the only course to take.

Impact and Aftermath of Partition

“Leave India to God. If that is too much, then leave her to anarchy.” — Mahatma Gandhi, May 1942

The partition of India left both India and Pakistan devastated. The process of partition claimed many lives in riots, rapes, murders, and looting. Women, especially, were used as instruments of power by the Hindus and the Muslims.

Fifteen million refugees poured across the borders to regions completely foreign to them because their identities were rooted in the geographical home of their ancestors, not their religious affiliations alone. In addition to India’s partition, the provinces of Punjab and Bengal were divided, causing catastrophic riots and claiming the lives of Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs alike.

Many years after partition, the two nations are still trying to heal the wounds left behind. The two countries began their independence with ruined economies and lands without an established, experienced system of government. They lost many of their most dynamic leaders, such as Gandhi, Jinnah and Allama Iqbal, soon after the partition. Pakistan later endured the independence of Bangladesh, once East Pakistan, in 1971. India and Pakistan have been to war multiple times since the partition and they are still deadlocked over the issue of possession of Kashmir.

Timeline

1600: British East India Company is established.

1857: The Indian Mutiny or The First War of Independence.

1858: The India Act: power transferred to British Government.

1885: Indian National Congress founded by A. O. Hume to unite all Indians and strengthen bonds with Britain.

1905: First Partition of Bengal for administrative purposes. Gives the Muslims a majority in that state.

1906: All India Muslim League founded to promote Muslim political interests.

1909: Revocation of Partition of Bengal. Creates anti-British and anti-Hindu sentiments among Muslims as they lose their majority in East Bengal.

1916: Lucknow Pact. The Congress and the League unite in demand for greater self-government. It is denied by the British.

1919: Rowlatt Acts, or black acts passed over opposition by Indian members of the Supreme Legislative Council. These were peacetime extensions of wartime emergency measures. Their passage causes further disaffection with the British and leads to protests. Amritsar Massacre. General Dyer opens fire on 20,000 unarmed Indian civilians at a political demonstration against the Rowlatt Acts. Congress and the League lose faith in the British.

1919-Montagu-Chelmsford Reforms (implemented in 1921). A step to self-government in India within the Empire, with greater provincialisation, based on a dyarchic principle in provincial government as well as administrative responsibility. Communal representation institutionalised for the first time as reserved legislative seats are allocated for significant minorities.

1920: Gandhi launches a non-violent, non-cooperation movement, or Satyagraha, against the British for a free India.

1922: Twenty-one policemen are killed by Congress supporters at Chauri-Chaura. Gandhi suspends non-cooperation movement and is imprisoned.

1928: Simon Commission, set up to investigate the Indian political environment for future policy-making, fails as all parties boycott it.

1929: Congress calls for full independence.

1930: Dr. Allama Iqbal, a poet-politician, calls for a separate homeland for the Muslims at the Allahabad session of the Muslim League. Gandhi starts Civil Disobedience Movement against the Salt Laws by which the British had a monopoly over production and sale of salt.

1930-31: The Round Table conferences, set up to consider Dominion status for India. They fail because of non-attendance by the Congress and because Gandhi, who does attend, claims he is the only representative of all of India.

1931: Irwin-Gandhi Pact, which concedes to Gandhi’s demands at the Round Table conferences and further isolates Muslim League from the Congress and the British.

1932: Third Round Table Conference boycotted by Muslim League. Gandhi re-starts civil disobedience. Congress is outlawed by the British and its leaders.

1935: Government of India Act: proposes a federal India of political provinces with elected local governments but British control over foreign policy and defense.

1937: Elections. Congress is successful in gaining majority.

1939: Congress ministries resign.

1940: Jinnah calls for establishment of Pakistan in an independent and partitioned India.

1942: Cripps Mission to India, to conduct negotiations between all political parties and to set up a cabinet government. Congress adopts Quit India Resolution, to rid India of British rule. Congress leaders arrested for obstructing war effort.

1942-43: Muslim League gains more power: ministries formed in Sindh, Bengal and North-West Frontier Province and greater influence in the Punjab.

1944: Gandhi released from prison. Unsuccessful Gandhi-Jinnah talks, but Muslims see this as an acknowledgment that Jinnah represents all Indian Muslims.

1945: The new Labour Government in Britain decides India is strategically indefensible and begins to prepare for Indian independence. Direct Action Day riots convince British that Partition is inevitable.

1946: Muslim League participates in Interim Government that is set up according to the Cabinet Mission Plan.

1947: Announcement of Lord Mountbatten’s plan for partition of India, 3 June. Partition of India and Pakistan, 15 August. Radcliffe Award of boundaries of the nations, 16 August.

1971: East Pakistan separates from West Pakistan and Bangladesh is born.

Literature and Film Dealing with the Partition of India

- Bhalla, Alok, ed. Stories About the Partition of India. New Delhi: Harper Collins, 1994.

- Desai, Anita. Clear Light of Day. New York: Penguin, 1980.

- Garam Hawa (“Hot Air”). Dir. M.S. Sathyu. Unit 3 MM, 1973.

- Ghosh, Amitav. The Shadow Lines. New York: Oxford UP, 1995.

- Kesavan, Mukul. Looking Through Glass. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1995.

- Manto, Sadaat Hassan. Best of Manto. Ed. and Trans. Jai Ratan. Lahore: Vanguard, 1990.

- Rushdie, Salman. Midnight’s Children. New York: Penguin, 1991.

- Sahni, Bhisham. Tamas. New Delhi: Panguin, 1974.

- Sidhwa, Bapsi. Cracking India. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 1991.

- Singh, Khushwant. Train to Pakistan. New York: Grove Press, 1956.

Print Sources

- Azad, Maulana Abul Kalam. India Wins Freedom. New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1960.

- Hasan, Mushirul, ed. India’s Partition: Process, Strategy, and Mobilization. New York: Oxford UP, 1993.

- Kanitkar, V.P. The Partition of India. East Sussex: Wayland, 1987.

- Lord Birdwood. India and Pakistan: A Continent Decides. New York: Frederick A. Praeger, 1954.

- Philips and Wainwright, eds. The Partition of India: Policies and Perspectives 1935-1947. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1970.

- Sharma, Kamalesh. Role of Muslims in Indian Politics (1857-1947). New Delhi: Inter India, 1985.

Author: Shirin Keen, Spring 1998

Last edited: October 2017

3 Comments

Thank you for the information on the partition of India.

The role of the British, Gandhi and Jinnah should not be ignored. British Vice Roy of India in 1905 decided to destroy the nationalist movement of India, in which Bengal was then playing the most prominent role, by dividing up Bengal and created a Muslim dominated province by combining East Bengal and Assam. At the same time, he has asked the Muslim Nawab of Dakha, now the cpital of Bangladesh to establish the Muslim League, promoted Muslims into the police and the Army. That was the beginning of the Divide and Rule policy of the British. On top of that British protege Sir L. Gokhale asked MK Gandhi to come from South Africa to India to destroy The Congress Party by getting rid of the leaders who wanted freedom in preference for a group of sycophantic followers of Gandhi. Gandhi started his Non-Cooperation movement in 1919 not for the freedom of India but to reestablish the pro-British Sultan of Turkey, the Khalifa of the Muslims. Gandhi refused to cooperate with the Muslim leaders who were against the partition of India and Jinnah, who was promoted by the British to divide India. In 1943, Gandhi prepared a plan to partition India, but Jinnah wanted more land. In 1946-47, going against The Congress Party Gandhi and his closest followers Nehru and Patel agreed immediately to the British proposal to divide India and refused to take any responsibility for the non-Muslims who, everyone knew, would be slaughtered in the proposed Pakistan.

Pingback: Notes on Dhaka – the chaotic capital of Bangladesh