Which Yeats?

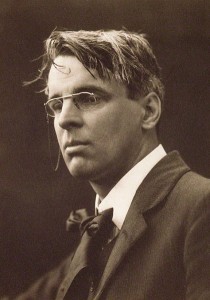

There are many versions of William Butler Yeats (b 1865 d 1939), Ireland’s most famous poet, dramatist, critic, and Senator. Variously claimed by nationalists, occultists, fascists, modernists, Romantics, and postcolonialists, Yeats’s life and work are open to many interpretations. As a writer who devoted himself to building Irish culture and literature, Yeats’s position as a postcolonial figure seems obvious. At the same time, he was a member of the Anglo Irish Ascendancy and flirted with fascist ideas in his old age. This article summarizes some of the most compelling arguments for Yeats as a major postcolonial artist.

(See Representation)

Critical Overview

This discussion rests on the question of Ireland’s place as a postcolonial nation. In their foundational reader, The Empire Writes Back, Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffiths, and Helen Tiffin exclude Ireland from the list of postcolonial nations, even though Canada and the United States are included. Even so, they include Ireland within certain points of their discussions. Edward Said, in Culture and Imperialism, argues for Yeats as a decolonizing writer, and makes the claim that Ireland is indeed a postcolonial nation. David Lloyd’s essay, “The Poetics of Politics: Yeats and the Founding of the State,” explores the connections between Yeats’s poetry and nationalism. Interrogating Yeats’s position as both postcolonial and colonialist, Seamus Deane’s Celtic Revivals raises important questions about images of nation and history. Jahan Ramazani uses Yeats to interrogate postcolonial studies, and vice versa, coming to the conclusion that Yeats’s work as a nation-maker qualifies him for inclusion as a postcolonial (Ramazani prefers the term “anticolonial”) poet. Finally, Declan Kiberd works with Yeats’s literary reconstructions of childhood and argues that Yeats’s search for a writing style mirrors a quest for selfhood in a postcolonial context. (See also Gayatri Spivak)

Biography

The Early Years: Sligo, London, Gonne, Folklore, and Mysticism

Born in Dublin in 1865, Yeats was the son of a painter, John Butler Yeats, and Susan Pollexfen Yeats, whose family lived in Sligo, in the Northwest of Ireland. Yeats spent much of his childhood in Sligo, and repeatedly returned to those memories in his work. His homesickness when the family moved to London in 1874 and his sense of isolation in an English school resurface in his Autobiographies. After briefly attending art school, Yeats devoted himself both to Irish literature societies in London and Dublin and his own literary development.

Maud Gonne, whom Yeats met in 1889, would become the inspiration for most of his love poetry. Though Yeats never agreed with Gonne’s militant Republicanism, he continued to write about her all of his life. In the 1890s, Yeats became fascinated by Irish folklore, and published collections of Irish legends and original poems inspired by mythological Irish figures (see Myths of the Native). During this period, Yeats joined the Theosophical Movement, and became a member of the Order of the Golden Dawn. This mystical, esoteric group, devoted to the supernatural, supplied Yeats with important symbolic systems. He developed an interest in Indian mysticism.

The Abbey Theater and The Irish Revival

In 1904, Yeats, along with Lady Augusta Gregory and Annie Horniman, founded the Abbey Theater. At the Abbey, Yeats sought to create an Irish theater and educate the Irish public by offering a place for the performance of works by Irish dramatists (see Postcolonial Performance and Installation Art). This laudable goal met with difficulties. The 1907 Playboy Riots, in response to supposed indecency in John Millington Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World, infuriated Yeats, who supported Synge’s play in the face of pushes for censorship. After discovering ancient Japanese Noh Drama in 1916, Yeats began to incorporate Noh conventions (little scenery, heavy symbolism, stylized movements) into his own drama. The Abbey Theater and Yeats’s poetry made important contributions to the Irish Revival, a resurgence of Irish drama, poetry and prose from the Victorian period to the 1920s. (See the Field Day Theatre, Brian Friel)

Politics and Marriage

Though frustrated by the Dublin reaction to Synge’s Playboy of the Western World, Yeats’s attitude toward Ireland changed again in 1916. The Easter Rising of 1916, when roughly 700 Irish volunteers took over parts of Dublin and proclaimed an Irish Republic, inspired in Yeats a new nationalism. His elegy for those executed by the British, “Easter 1916,” eulogizes the dead while retaining an ambivalent attitude toward violent resistance. In 1917, Yeats married Englishwoman Georgie Hyde-Lees. Yeats believed that his wife was capable of acting as a spirit medium, and based much of his mystical work, A Vision (1925), on her automatic script. The couple had a son and daughter and lived in a Norman castle, Thoor Ballylee. From 1922 to 1928, Yeats served as a Senator for the Irish Free State, and was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1923. Yeats died in the South of France in 1939, and was buried in 1940 in Sligo.

The Critics on Yeats and Postcolonialism

This section will provide abstracts of a selection of the major critical contributions to the question of Yeats and postcolonialism, arranged chronologically. For more information on these texts and suggestions for further reading, please see the bibliography.

On Seamus Deane’s Celtic Revivals (1985)

Seamus Deane’s essays debate Yeats’s position as postcolonial writer. At times Deane finds in Yeats a strong cultural nationalist, but just as often he accuses Yeats of writing out of reductive visions of Ireland. He interrogates Yeats’s position in two essays in this volume, “Yeats and the Idea of Revolution” and “O’Casey and Yeats: Exemplary Dramatists.” The first essay implicates Yeats in “inventing an Ireland amenable to his imagination” (38). Deane reads the connections between death and sex in Yeats’s play A Full Moon in March: “Sex and violence produce poetry. Aristocrat and peasant produce, out of a violent fusion, art” (47). At the same time, Deane sees in Yeats’s attitude towards Ireland and England a conflict that he compares to V. S. Naipaul’s position on India and England: “the English left behind in their twentieth century colonies one of their most enduring inventions — a concept of Englishness. . . . The whole Irish Revival is a reaction against this attitude, a movement towards the colony and a way from the mother country, a replacement of ‘Englishness’ by ‘Irishness’” (48). Though Deane has problems with some of Yeats’s “colonialist” dramatizations of Ireland, he investigates this issue in postcolonial terms. Deane’s second essay on Yeats and O’Casey finds in Yeats “a more profoundly political dramatist than O’Casey, that it is in his plays that we find a search for the new form of feeling which would renovate our national consciousness” (122). Deane’s writings explore the question of Yeats as postcolonial writer.

On Edward Said’s “Yeats and Decolonization,” from Culture and Imperialism (1993)

After acknowledging Yeats’s position as a canonical European, modernist poet, Said introduces the notion of Yeats as an “indisputably great national poet who during a period of anti-imperialist resistance articulates the experiences, the restorative vision of a people suffering under the domination of an offshore power” (220). Said goes on to place Ireland in the context of colonialism, and defines nationalism as the “mobilizing force that coalesced into resistance against an alien and occupying empire on the parts of people possessing a common history, religion, and language” (223). (See Mimicry, Ambivalence, and Hybridity) The essay moves towards Yeats as a postcolonial poet as Said discusses the connection between geography, place names, and the decolonization of both land and language. (See Geography and Empire) Grouping Yeats with other English-speaking African and Caribbean authors, Said describes an “overlapping” between Yeats’s “Irish nationalism with his English cultural heritage” (227). After questioning nativism in terms of Yeats’s writing, Said argues that “Yeats’s slide into incoherence and mysticism during the 1920s” relates to a limited nativist perspective (231). Yeats’s preoccupations with an “ideal community” and with history as “the wrong turns, the overlap, the . . . occasionally glorious moment,” Said argues, place him in the company of “all the poets and men of letters of decolonization” (232). Said ends by placing Yeats somewhere along the way to full postcolonialism: “True, he stopped short of imagining full political liberation, but he gave us a major international achievement in cultural decolonization nonetheless” (239).

On David Lloyd’s “The Poetics of Politics: Yeats and the Founding of the State” from Anomalous States: Irish Writing and the Post Colonial Moment (1993)

Emphasizing the important political “discomfort” that Yeats’s poems still cause, Lloyd explores the relationships between Yeats’s poetry and Irish nationalism. Applying later Yeats to the poet’s earlier work, Lloyd detects Yeats’s discomfort with the nationalist force of his own drama and poetry. The famous early Yeats play, Cathleen Ni Houlihan, inspired such fervent nationalism that in later life Yeats would ask: “Did that play of mine send out certain men to the English shot?” In Lloyd’s view, this concern is “by no means an overweening assessment of the extraordinary part his writings played in the forging in Ireland of a mode of subjectivity apt to find its political and ethical realization in sacrifice to the nation yet to be” (59). Lloyd addresses the paradoxical emphasis on foundation and demise in Yeats’s poetry (68). At the end of the essay, Lloyd turns to Yeats’s female characters, and raises questions about “the antagonism between certain feminisms and the nationalism of the state” (81).

On Declan Kiberd’s Inventing Ireland (1995)

Kiberd spends his first chapter, “Childhood and Ireland,” on Yeats, discussing the effect of the poet’s Sligo childhood on both his writing and his vision of Ireland. He questions the ways that Yeats’s early work, like other Revival texts, “which so nourished the national feeling, were often British in origin, and open to the charge of founding themselves on the imperial strategy of infantilizing the native culture” (102). Kiberd weighs in with other critics on the strong connection between Yeats’s writing and place: “In emphasizing locality, Yeats, Synge and Lady Gregory were deliberately aligning themselves with the Gaelic bardic tradition of dinn-sheanchas (knowledge of the lore of places)” (107). Kiberd offers a reading of the differences between Irish and British definitions of culture: “In (Yeats’s) estimate, a true culture consisted not in acquiring opinions but in getting rid of them” (111). “Innocence,” then, “is not inexperience, but its opposite” (112). In the next chapter, “The National Longing for Form,” Kiberd argues that Yeats and Whitman, as postcolonial writers, both perform “a search for a national style” (116). This chapter explores the relationship between the literature of the “cultural colonies” and the “parent country” (115). Kiberd then presents a fascinating argument for Yeats’s search for his own style as a form of “self-conquest” (120). Connecting literature and self, Kiberd argues that for both Whitman and Yeats “the decolonization of the body was a task almost as important as the decolonization of the native culture” (127). Investigating ideas of culture, and arguing for the search for a new style as a quest for a new self and nation, Kiberd reveals connections between Yeats and Whitman as writers of decolonization.

On Jahan Ramazani’s “Is Yeats a Postcolonial Poet?” (1998)

Ramazani’s fascinating essay begins by outlining the arguments for and against Yeats’s inclusion as a postcolonial writer. Acknowledging Yeats’s “whiteness, and his affiliation with the centuries old settler community of Anglo-Irish Protestants, Ramazani argues that due to his “anticolonial resistance to British cultural domination and his effort to transform the degraded colonial present by recuperating the precolonial past,” Yeats warrants examination as an anticolonial writer. If we place Yeats “under the postcolonial microscope, the many different shapes and sizes of postcoloniality need to be distinguished.” Ramazani then discusses postcolonialism in terms of Yeats and Ireland, arguing that the term “anticolonial” replace “postcolonial.” With “influences on writers as diverse as Derek Walcott and Lorna Goodison, Raja Rao and A. K. Ramanujan, Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka,” Yeats belongs to the postcolonial tradition of hybridization. Ramazani continues to position Yeats with postcolonial, or anticolonial writers: “When Yeats, speaking at a political gathering in 1898, declared that the English empire ‘has been built on the rapine of the world,’ he anticipated Frantz Fanon‘s claim” (81). In terms of Irish cultural history, Ramazani claims that through their “Revival, the poets have turned a corpse like Ireland into a living, vibrant, even awe-inspiring ‘imagined community.’” Finally, Ramazani interrogates Yeats’s use of Indian symbols and characters as neither completely Orientalist nor affiliating, but sees his attraction to India because it “represents the Unity of Culture he wished for Ireland.” Ramzani concludes that as a nation-maker and a writer of hybridization, Yeats should be considered an anticolonial writer. (See also Transnationalism and Globalism)

For more Irish entries see:

2. Brian Friel

3. Roddy Doyle

4. Eavan Boland

Bibliography

- Ashcroft, Bill, Griffith, Gareth, and Tiffin, Helen. The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures. New York: Routledge, 1989.

- —. (eds.) The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. London: Routledge, 1995.

- Brown, Malcom. The Politics of Irish Literature from Thomas Davis to W. B. Yeats. Seattle: U Washington P, 1972.

- Cairns, David and Richards, Shaun. (eds.) Writing Ireland: Colonialism, Nationalism and Culture. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1988.

- Deane, Seamus. Celtic Revivals: Essays in Modern Irish Literature 1880-1980. Winston Salem: Wake Forest UP, 1985.

- —. “Yeats: the Creation of an Audience.” Tradition and Influence in Anglo- Irish Poetry. Terence Brown and Nicholas Grene. (eds.) Totwa: Barnes and Noble, 1989. pp. 31-46.

- Eagleton, Terry, Jameson, Fredric, and Said, Edward. (eds.) Nationalism, Colonialism and Literature. Minneapolis: U Minnesota Press, 1990.

- Eagelton, Terry. “Yeats and Poetic Form.” Crazy John and the Bishop and Other Essays on Irish Culture. Notre Dame: U of Notre Dame P, 1998.

- Ellmann, Richard. The Identity of William Butler Yeats. New York: Oxford UP, 1964.

- Foster, John Wilson. “Yeats and the Easter Rising.” Colonial Consequences:Essays in Irish Literature and Culture. Dublin: Lilliput, 1991. pp.133-148.

- Foster, R. F. Paddy and Mr. Punch: Connections in Irish and English History. London: Penguin, 1993.

- —. W. B. Yeats, A Life. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1997.

- Frazier, Adrian. Behind the Scenes: Yeats, Horniman, and the Struggle for the Abbey Theater. Berkeley and Los Angeles: U California P, 1990.

- Kiberd, Declan. Inventing Ireland. London: Jonathan Cape, 1995.

- Lloyd, David. “The Poetics of Politics: Yeats and the Founding of the State”. Anomalous States: Irish Writing and the Post Colonial Moment. Dublin: Lilliput, 1993. pp. 59-87.

- Llyons, F. S. L. Culture and Anarchy in Ireland 1890-1939: From the Fall of Parnell to the Death of Yeats. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1979.

- Ramazani, Jahan. “Is Yeats a Postcolonial Poet?.” Raritan vol.17 no. 3 (Winter 1998): pp. 64-89.

- Said, Edward. “Yeats and Decolonization.” Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage, 1993. pp. 220-239.

- Watson, G. J. Irish Identity and the Literary Revival: Synge, Yeats, Joyce and O’Casey. Washington: Catholic U of American P, 1979.

- Yeats, William Butler. Autobiographies. New York: Scribner, 1999.

- —. The Yeats Reader. Richard J. Finneran (ed.). New York: Scribner, 1997.

- —. The Collected Poems of W. B. Yeats. Richard J. Finneran (ed.). New York: Scribner, 1997.

Related Sites

The Atlantic Monthly: All Ireland’s Bard. Seamus Heaney reviews R. F. Foster’s biography, Yeats, A Life.

http://www.theatlantic.com/issues/97nov/yeats.htm

The Atlantic Monthly’s Reading of “Easter 1916″ by Peter Davidson, Philip Levine,and Richard Wilbur. Article on “Easter 1916.”

http://www.theatlantic.com/unbound/poetry/soundings/yeats.htm

The Atlantic Monthly: William Butler Yeats by Louise Brogan. A 1938 article on Yeats as an older poet with an overview of his life.

http://www.theatlantic.com/unbound/poetry/yeats/bogan.htm

Bartelby.com’s index to Yeats’s Responsibilities and Other Poems, The Wind Among the Reeds, and The Wild Swans at Coole.

http://www.bartleby.com/people/Yeats-Wi.html

Emory’s Special Collections Yeats Page

http://findingaids.library.emory.edu/documents/yeats600/

Author: Elizabeth Brewer, Spring 2000

Last edited: May 2017