Settlement Planning in the Assyrian Empire

The Assyrian Empire, at its height, controlled nearly one million square kilometers of land, stretching from Iran to Egypt. Such a massive empire appropriately brought changes to settlement systems – both those already established and brand new settlements. By investigating Qach Rresh on the Erbil Plain, we are exploring what a brand new village founded during the empire’s most powerful period looks like, and what that can tell us about Assyrian strategies of settlement.

Deportee Populations in the Imperial Heartland

The Assyrian Empire expanded through massive warfare and violence, conquering peoples who were originally part of other states, kingdoms, or nomadic groups. As a tactic of controlling these populations after they had been conquered, the Assyrian Empire practiced “deportation” – or, moving and resettling these peoples in different locations throughout the empire (sometimes thousands of kilometers away). This served two functions: it depopulated the conquered towns to weaken them further, and it extracted people from their communities and familiar land to prevent revolts. Furthermore, it has been argued that these new populations provided a source of labor that was otherwise scarce in parts of the empire. Were deportees living at Qach Rresh?

Agricultural Production in the Iron Age

Provisioning the massive capital cities and the extensive army of the Assyrian Empire was no small feat. Agricultural staples such as cereals and legumes had to be in ready supply to feed the growing population. This, naturally, led to an intensification of agriculture in the empire. At Qach Rresh, we are carefully investigating the storage rooms of large buildings to recover the remains of crops that were held there. What was being grown at this site, and how did this change after the collapse of the empire?

The 2023 Season

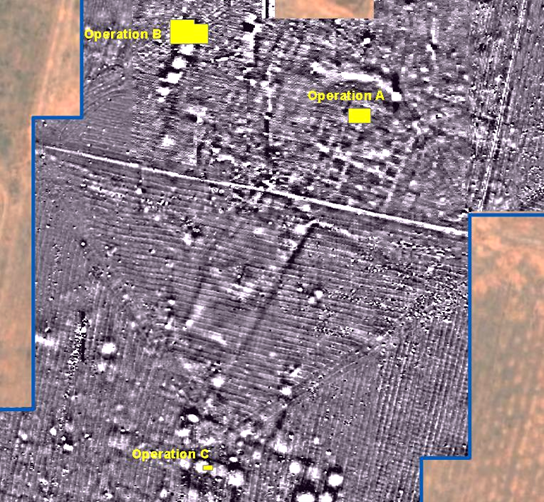

The 2023 season lasted 5 weeks (April 30-June 4) and involved expanding Operations A and B, opening Operation C, and expanding magnetometry survey coverage to the north and south.

Qach Rresh is remarkably well-suited for geophysical survey investigation. In addition to Buildings A and B identified in the results from 2021, we now have detected a large complex of rooms further south, consisting of at least 12 rooms in a roughly linear arrangement with additional architectural features present around them. The rooms making up this structure (which we are calling “Building C”) appear brightly in the magnetometry, which indicates that they are likely filled with the same dumping debris that Op B. contains. At least 10 rooms have similarly high magnetic signatures, indicating that they are filled with ashy debris and ceramics. Other, similar highly magnetic anomalies in the south likely indicate more rooms filled with debris, though this is more difficult to tell from magnetometry alone.

Most interesting to our investigations is the presence of at least two large structures measuring 120x50m and 60x30m just north of this new Building C (and south of Building A). These are likely the magnetic signature of large animal pens, where iron-rich dung accumulates along the fenceline of such pens and creates a higher magnetic signature than the surrounding soil. Another possible pen is located to the direct east of these two, but the magnetic signature is faint. Between Building C and the largest animal pen, there is a possible gate or entrance between the two measuring 5m wide. This building is evidently associated with the animal pens. The assumed association continues when observing a fainter architectural structure directly to the west of the main pen and to the south of the smaller pen. This structure was possibly used for staging animals for counting (during Assyrian taxation) or butchery.

Operation A

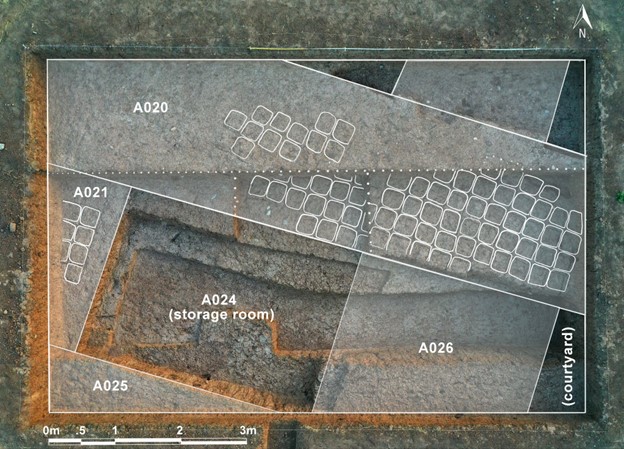

Operation A was continued from the 2023 excavations. This year, the trench was led by Swerida and Maynard. The excavations of Op.A had two main goals this season: one, to better understand the relationship of the wall (A-013) found during the 2022 field season to its surrounding architecture, and two, the relationship of probable rooms and floor surfaces, also newly discovered last year. In the first week, we expanded Op. A northward from its original 3x10m size to 5x10m in an effort to reconstruct the entirety of the wall (now termed wall A-20) and catch an additional corner of a storeroom to the NE. After excavating roughly 30 cm through a soil matrix heavily affected by plowing and root activity, we found a layer with a dense concentration of calcium carbonate (CaCO3) crystals marking the preserved course of the continuation of mudbrick wall A-20. After shaving this layer off by about 5 cm in order to find the mortar lines, we began to delineate individual bricks. Although the mudbricks of wall A-020 were uniformly of 33×33 cm dimensions, we found that the original builders of this wall did not build each wall course precisely on top of each other. Between the three exposed courses of brick at various points of wall A-020, each row was placed slightly differently from the row above it. Moreover, the builders included additional materials, such as small and medium-sized rocks, ceramic sherds, and animal bones, to create individual mudbricks. As preserved, wall A-020 is roughly 7 rows wide and 4 courses deep.

Operation B

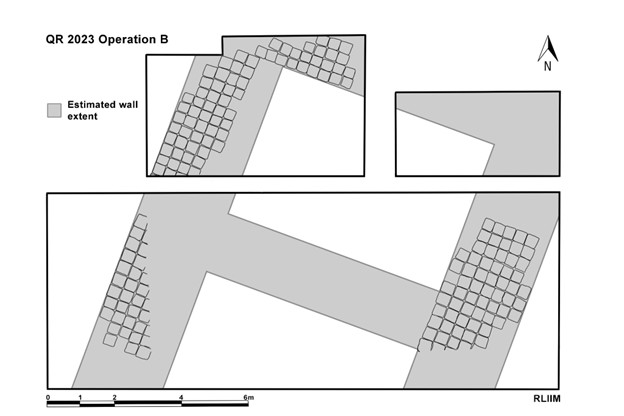

Operation B was continued from the 2023 excavations. This year, the trench was led jointly by Kaercher and Creamer. Over the course of the season, we expanded Op. B from its original 10x10m size to 11x16m with the goal of exposing the entirety of Room 1 (the northernmost room seen in the magnetometry data) and its associated walls. After excavating down roughly 30cm, we began to be able to identify the eastern mudbrick wall bounding Room 1. In order to define individual bricks, we excavated down further to 50cm before beginning to pick out the mortar lines in between bricks, which were able to be distinguished by color (slightly grayer than the reddish brick) and texture (crenelated) (see Fig. 13). Once these were identified, we were able to measure the entire width of the wall to be around 2.7m thick – comparable to the walls in Op. A (and supporting our theory that both Buildings A and B were constructed at the same time). We then expanded the eastern part of the trench 3m to the north and excavated down to 50cm to find the northeastern corner of Room 1.

In addition to expanding Op. B to the east, we expanded the northernmost part of the trench 4m to the west to identify the western wall of Room 1 and its individual mudbricks. Last year in 2022 we had been able to identify the probable NW corner of Room 1 based on the stark difference between ashy, ceramic-filled deposit and thicker, uniform sediment which bounded it to the north and west. Indeed, we were able to confirm the corner this season and designate several rows of mudbricks in both the western and northern walls of Room 1. We continued to trace the western wall in the western half of Op. B, where we excavated down a further 20cm from last year to bring it down to level with the northern trench.

Our effort to identify the southern wall of Room 1 was more difficult. Near the beginning of the season, we expanded the trench 1m to the south to try and find mudbrick, but were still unable to identify a wall running E-W. We realized, while excavating what we believed to be the fill of Room 1, that there was preserved mudbrick below several layers of trash deposition (roughly 1.2m below surface). Excavating this further, we were able to identify it as part of the southern wall for Room 1. The final size for Room 1 measures roughly 7.5x6m.

Operation C

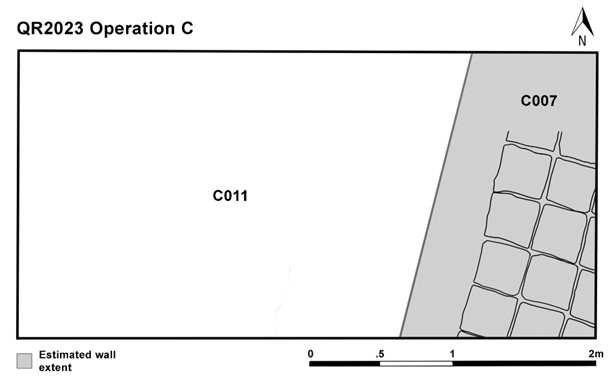

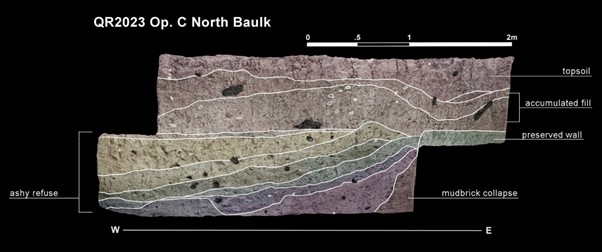

Operation C was started on May 28 2023 with the intention to investigate a small area of one of the new buildings to the south identified in the magnetometry. We laid out a 4x2m trench to test the contents of one of the rooms (see Fig. 17). Kak Ahmed Jodat was the trench leader of Op. C. In five days of excavation, we reached a depth of 1.53 m.

The room which Operation C intersects, as its magnetic signature indicated, was used as a trash deposition area after its main use (likely during the Assyrian imperial period). We discovered a single wall running NNE-SSW protruding roughly one meter into the trench’s eastern side with several of its mudbricks able to be defined. These measured roughly 34x34cm, equivalent to those in Operation B. This is likely the dividing wall between rooms, as can be seen in Fig. 7.

There were several layers of ash deposit and mudbrick collapse, followed by trash deposition which yielded a high number of sherds and faunal remains. Unlike the trash deposition event layers in Operation B which can be quite thin (possibly indicating individual household trash deposits), the ashy layers and trash layers in Op. C were quite thick (roughly 8-10cm thick on average) and might indicate larger amounts of refuse being deposited in these southern buildings at one time. All trash layers slope down from the preserved wall, which may indicate that this wall had already deteriorated by the time the rooms were used as dumps.

The 2022 Season

With a season lasting 5 weeks (from August 31 – October 2, 2022) the RLIIM team opened two trenches over the main building remains at Qach Rresh.

Both the buildings in Operation A and Operation B were difficult to identify based on excavation alone, due to significant deterioration in the mudbrick. By using the magnetometry data together with the excavation, we were able to come to several conclusions about the site after one season:

- While we believe the buildings to have been constructed in the Neo-Assyrian period, many of the artifacts collected from the Qach Rresh excavations likely date to the post-Assyrian phase of the Iron Age (c. 600-300 BCE). This conclusion is based on the post-Assyrian forms of the ceramics and the common use of grit instead of chaff as a temper.

- The rooms of Building B (in Operation B) were used as a dump in the post-Assyrian period.

The placement of Operations A (southeast trench) and B (northwest trench) over the building walls identified in the magnetometry.

In Operation A we excavated down in 20cm intervals with the intention of uncovering a large set of walls bounding the northwestern part of the courtyard in the main building identified through magnetometry. At a depth of around 50cm, the texture of the soil matrix began to harden, becoming thick and difficult to excavate. While the walls were difficult to identify due to this uniform matrix, we were able to distinguish the wall (A-013) running roughly from NW-SE based on a pit that had been cut into the fill of the building. The pit itself was filled with ash, charcoal, animal bone, and broken pottery.

It quickly became evident that the western half of the trench was very similar in soil type to much of Op. A, where calcium carbonate crystals were intermingled with dark brown, thick soil. In the eastern half of the trench, however, we began to collect large amounts of sherds and animal bones beginning at a depth of 35cm. To focus our efforts, we separated the trench in half and continued to excavate in the eastern half, while also opening a 4x5m area in the northeastern corner of the trench. Based on soil color and texture, we were able to estimate the orientation and thickness of the mudbrick wall bounding the room on its western side. We designated this wall before continuing to excavate the room’s fill.

The room excavated in Building B (Op. B) this season contained at least 130cm of fill from trash deposition. Below these multiple deposition events (which can be identified in the stratigraphy of the baulk) there was what appeared to be roughly 55cm of mudbrick collapse, likely from the roof of the building. Below this, there was a 30cm thick layer of hard-packed clay with very few artifacts. We interpret this layer to be the remains of the foundation trench constructed before Building B was built.

While initially we approached Qach Rresh believing it to be occupied only in the late Neo-Assyrian period (c. 750-600 BCE) we now recognize that it was also used in the post-Assyrian period. The buildings may have been constructed in the Neo-Assyrian period, abandoned, and then reused in the post-Assyrian period, based on preliminary interpretations of the ceramic material. Overall, we are also interested in the potential to investigate the post-Assyrian occupation of the Erbil Plain, considering it has been largely underrepresented in archaeological studies.

The section drawing of Operation B’s sounding (B-019), showing several deposition events.