Many marble cineraria feature small-scale portraits and popular portrait conventions seen in other types of monuments.

Of the different types of decoration on marble cineraria, the notion of portraits on urns is particularly complicated. What the composition is meant to portray is not always clear, and interpretation can be complicated further when considered with the inscription on an urn.

For example, the cinerary urn of Domitius Primigenius at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York indicates in the dedicatory inscription that he had the urn made for himself, his freedmen/freedwomen, and their posterity. The figural scene, however, appears to give prominence to a (living) woman reclining on a couch. While a wife is nowhere mentioned in the inscription, the viewer would assume that the central male figure is Domitius Primigenius depicted as a devoted or pious husband. Is the central male figure Domitius Primigenius and the woman his unnamed wife? Is she a freedwoman? Are the young slaves at left and right meant to stand in as future freedmen noted in the inscription?

Many urns bear the resemblance of portraits such as these, portraits that may not necessarily correspond exactly to inscriptions on the urn. The pairing of portraits with inscriptions on urns presents the viewer with a dynamic, nuanced composition imbued with cultural values. Yet, many more cineraria show blank inscription tablets. These have proven extremely problematic for interpreting the objects as a corpus, and I return to this issue frequently throughout this project.

By analyzing the technical details of portrait likenesses on cinerary urns in relation to the heads of peripheral figures, such as erotes, we can also begin to reevaluate notions of specialized portrait artists more broadly in studies of Roman art production. The three portraits on this urn (above) in Cleveland all exhibit the same high quality and precision (relative to other urns with portrait heads) as the erotes. These portrait likenesses also do not differ significantly from portraits on Roman sarcophagi for example. Certain cineraria featuring portraits, however, may display varying degrees of precision and verism.

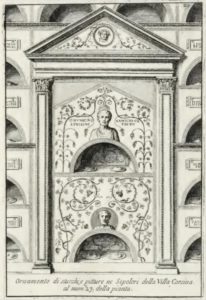

It seems likely that the carving of portraits on cinerary urns is more closely related to the practice of adding painted portraits around columbaria niches and inscriptions rather than elite sculpted portraits. This 1699 engraving of Bartoli shows painted portraits above terra-cotta ollie in the Villa Corsini columbarium tomb along the Via Aurelia.

The study of portraits on cineraria also presents numerous questions of antiquity and authenticity. Because of the small size and relatively generic craftsmanship of many urns, looters, traffickers, and forgers have favored urns from at least the seventeenth century to now. Additions of false inscriptions and ornament or the recarving of details further complicate modern research into cinerary urns. Glenys Davies, for example, has published on the extensive interventions of Giovanni Battista Piranesi with urns collected in the United Kingdom by Sir John Soane. This urn below, which presents a large, fine portrait bust of a young male on the lid, underwent restorations and additions by the workshop of Piranesi. It is therefore uncertain if the portrait is ancient, but more importantly, the lid likely belongs to another monument, either a cinerary altar from which it was separated or an altar from which it was cut. Moreover, the inscription is of dubious nature and shows signs of erasure, further casting doubt on the cinerary urn as a whole.

Similarly dubious or questionable urns bearing portraits sculpted with various skill levels and no known discovery contexts appear on the art market or in museums. In these cases, close technical analysis and careful but open-minded evaluation. Dismissal of stylistically unusual urns as forgeries denies the validity of provincial production and regional styles.

Another similar urn bearing two portraits sculpted into niches and accompanying herm portraits can be found in the Eskenazi Museum of Art at Indiana University. Many scholars and visitors have questioned the authenticity of the urn, but its features are not unprecedented. If we reevaluate the notion of mass production with a greater number of individual commissions and sculptors working with different skillsets and traditions, the authenticity of the Indiana cinerarium may not be so questionable.

Such questions remain open for now, as neither image nor inscription provide clear answers in many cases. However, by evaluating the production of urns from a technical standpoint, we can begin asking other questions beyond content and extending to the nature of portrait artists, sculptors, and sculptural production in metropolitan Rome more broadly.

Some rare examples of high status, high quality cineraria with portraits exist. One large cinerary altar associated with the Tomb of the Volusii family. Another smaller cinerarium of an individual also associated with the Volusii family presents a strong contrast the previous monument.

Running list of cineraria with portraits

Sinn Catalogue Numbers (with published photographs):

82

83

84

85

93

168

169

170

172

173

213 (broken off)

221

253

268

274

275

276

277

280?

281

282

292

293

298

299

372

378

382

385

406

414

415

417

419

432

433 Cornelius Philon

438 L. Cacius Cinna

452

454

455 (damaged)

456

457

458

459

462

464

478 Claudia Restituta

494

515

517

522

538

542

545

550

551

560

617

619 Vettidia Parthenope and M. Antius Hermetus

677

681

682 Aurelia Vitalis

683

Boschung:

95?

307?

550 Minucla Suavis

555 Hateria Superba

557

661? possibly cinerarium

779?

780

783

805

813

814?

818

823

836?

918?

992 Atia Iucunda

994

Elsewhere: