When reading the Escoffier chapter of Proust Was a Neuroscientist by John Lehrer, something that caught my eye was the experiment on wine tasters run by Frederic Brochet. It was astonishing that established wine tasters were unable to tell the difference between an ordinary wine from the more refined wines. Simply re-labeling cheap wine as expensive wine and vice-versa was enough to disorient their senses and make them think they were tasting something that they weren’t. This phenomenon of altering information that we collect with our own senses reminded me of my mother trying to get me to eat healthier when I was younger. She would try to disguise vegetables as snacks or meat, simply just tell me that vegetables were something that looked similar, carrots became cheese, broccoli became cauliflower (I used to like cauliflower), and tomatoes became cherries. Somehow, my mother was able to trick me into thinking that she was right, and I never second guessed her, but now that I think about it, how did I not? A tomato could never taste like a cherry and carrot never cheese. So what is at work here?

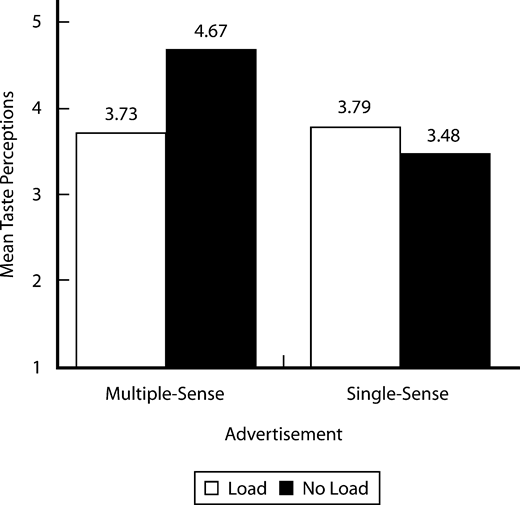

As it happens, a study with similar content to my own personal experience was run in 2009 by Ryan S. Elder and Aradhna Krishna. The study focused on how the advertising of food companies can invoke certain taste responses on their consumers. In a nutshell, food companies want to know which kind of slogans they can use to make their consumers spend more money. The study took chewing gum as the product it would use to measure taste responses based on whether the advertising method attacks multiple senses or just one (Aradhna and Elder 20091). The multiple sense slogan “Stimulate Your Senses” had a higher taste rating than the single sense slogan “Long Lasting Flavor” (Aradhna and Elder 20091). The results were scaled on a taste rating from 1-7, 7 being the best tasting and 1 being the worst tasting (Aradhna and Elder 20091). Out of a group of 10 students that tasted the two types of gum the multiple sense slogan earned a 5.39 average score while the single sense slogan had a 4.77 (Aradhna and Elder 20091). Aside from simply the taste, the multiple sense slogan was able to earn higher scores in other sense categories such as sight, smell, and touch (Aradhna and Elder 20091). A similar study was run for popcorn, but there were two conditions this time. There was a load group and a non-load group, the load group had to do a simple cognitive task before eating the food (memorizing names) (Aradhna and Elder 20091). Similarly, the multiple sense advertised product had higher mean scores, the data can be visualized in the graph below.

Figure from (Aradhna and Elder 20091)

The conclusion of these two studies in their respective study is that cognition is the key to what we think we sense. It doesn’t matter if something is actually good or bad, it depends on how good or bad we THINK something is before we even get to taste, touch, smell, hear, or see it. This is a classic example of top-down process interfering with bottom-up processing. Bottom-up processing is from input to processing. For example, if we eat an apple, our taste buds are able to communicate to our brain that it tastes sweet, sometimes bitter, and sometimes sour. The opposite is true for top-down processing, our condition interferes with the raw information given to us by our tongue. If something is sweet and it is labeled as sour, we perceive the food to be more sour than it actually is. This is exactly how I got tricked as a child and how advertising is able to elicit certain taste responses from consumers.

Bibliography: Ryan S. Elder, Aradhna Krishna, The Effects of Advertising Copy on Sensory Thoughts and Perceived Taste, Journal of Consumer Research, Volume 36, Issue 5, February 2010, Pages 748–756, https://doi.org/10.1086/605327

Aakash Parthasarathy