From the popularity of word cloud graphics to the pervasive “word count” feature of word-processing software, counting words with a computer may seem straightforward, but the digital scholarship expertise of text analysis entails a lot of complexity behind the scenes. Now imagine adding in the intricacy of a language that doesn’t rely on whitespace to separate words or provide meaning.

“In non-whitespace delimited languages — Japanese, Chinese, Tibetan — there’s no clear marker where a word breaks. Readers infer the breaks between words from the context,” says Emory University Japanese history professor Mark Ravina, who’s cohosting a four-day workshop, Japanese Language Text Mining: Digital Humanities Methods for Japanese Studies, at Robert W. Woodruff Library from May 30 – June 2, 2017.

“You can do a word count by running software over the text to find the logic and syntax, but because Japanese grammar has changed, you have to match the software to the century.”

Text analysis draws on a suite of tools to quantify textual elements in order to identify meaningful patterns. The approach provides “a crisp new perspective on something we’ve looked at a long time — it makes it possible to answer very old questions in seconds rather than lifetimes,” Ravina says. “There’s a lot of yield in terms of insight.”

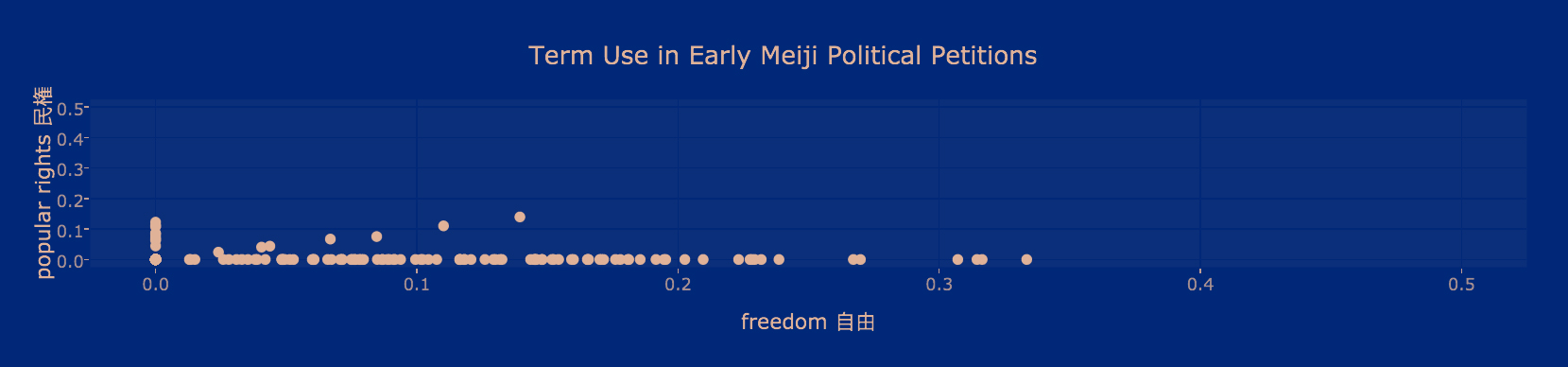

For example, he explains, this scatter plot shows the relative use of words related to a 19th-century movement in Japan that historians refer to as the “Freedom and Popular Rights Movement.”

- The word “minken” was coined to translate the Western political concept of popular rights.

- The word “jiyū” once meant wanton or reckless, but was recast to mean liberty or freedom.

- Text analysis of period documents shows that the two terms, though sometimes used together, had different connotations, and that many documents use one but not the other.

Special software is required to tokenize digitized texts, breaking up the blocks into words and morphemes. The National Institute for Japanese Language and Linguistics has developed tokenizing dictionaries for contemporary, literary, and classical Japanese, Ravina says, and using these to process multiple texts requires software skills in languages such as Bash, R, Python, and Ruby.

The workshop is bringing together some 20 Japan researchers and text mining experts around the shared goal of learning enough to collaborate with specialists in the complementary field. Participants were selected to attend from an array of institutions including Georgia Tech, Harvard, Okayama, UCLA, and Yale. While the workshop sessions are full, select materials will be made available online to support related scholarship.

Ravina is co-leading the workshop with Hoyt Long, associate professor of Japanese literature at the University of Chicago, and Molly Des Jardin, Japanese studies librarian at the University of Pennsylvania. In addition to support from the Japan Foundation and the RStudio software company, the workshop has several campus co-sponsors, including:

- East Asian Studies Program

- Department of Russian and East Asian Languages and Culture (REALC)

- Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS)

- Emory College of Arts and Sciences

- Emory Institute for Quantitative Theory and Methods (QuanTM)

- Emory Libraries

Graduate students, including Luke Hagemann and Virgo Morrison with the Department of History, are providing tutorial support to conference attendees.

Ravina, who has developed several courses drawing on digital humanities, says students are excited to learn new applications for coding skills they learned in statistics. “The most rewarding thing has been teaching at both the graduate and undergraduate level — I get to help with an astonishing range of projects.”