Every day a comic book hero named Antonio Valor, aka Brotherman, is fighting crime in a place called Big City, and, like many others in the field, he primarily pursues justice in print media. But now our hero can also save the day online via an interactive map of the fictional Big City, newly developed at the Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS).

To create this innovative space, ECDS specialists partnered with the comic book story’s creative team and Emory University’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library to extend the 2D world of the literature into a 3D world online.

“I was inspired to do this by reflecting on a simple map of William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, the fictional location where several of his novels take place,” says Clinton Fluker, ECDS’s outreach coordinator and Big City Maps project lead.

“When you’re teaching literary texts, you want to immerse students in the book’s setting as much as possible, though it’s always theoretical. Here, you can actually drop into the world itself,” explains Fluker, who recently completed his PhD at Emory about black speculative fiction.

Working with Pellom McDaniels, curator of African American collections at Rose Library, Fluker advised on the development of a new collecting interest in black comic books. “The Rose Library has one of the top collections related to black comic books in the nation,” according to McDaniels. “With the assistance of Fluker and the ECDS team, we are in a unique position to expand what we offer in terms of research materials and to do so through new and innovative ways to access content.”

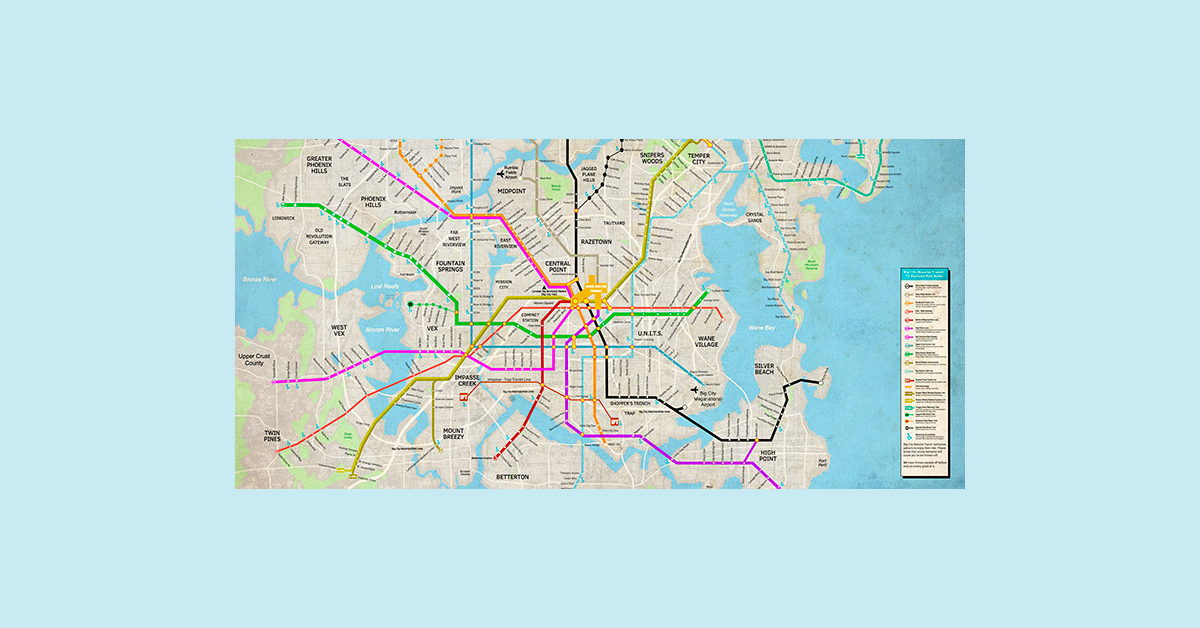

In the Brotherman storyline, which has been developing since the 1980s through comic books, novellas, and the first of several planned graphic novels, Big City itself is one of the main characters, Fluker explains. Its co-creators— illustrator Dawud Anyabwile and writer Guy A. Sims—detail dozens of locations in the text, accompanied by a map of a rounded peninsula with neighborhoods and a subway system.

To turn that print-based depiction into a digital format, ECDS team members improvised ways to use existing software developed for the real world to create a functional, fictional space.

“Dawud said he’d envisioned a city like Philadelphia, so we abstracted from that city and tried to make a realistic map,” says GIS Librarian Megan Slemons. “He had a fully developed world envisioned, so we had a lot to work with.”

Sims provided a list of places of interest in the city with details about their significance to the narrative, along with a map with the locations noted by hand. Using ArcMap, Slemons assigned latitude-longitude coordinates to each location and then, extending the data visualization functions of Tableau, she linked the custom coordinates with the map image of Big City. “Tableau was the best tool to allow us to create an interactive and realistic map of Big City, since it’s a place you can’t point to on a real-world map,” according to Slemons.

Visualization features allow site visitors to click on locations and view related story information and illustrations. And at several locations — such as Brotherman’s childhood home, where a dastardly deed happens in the first graphic novel — those clicks reveal immersive views based on wide-angle drone images taken in the Atlanta area. Anyabwile and colorist Brian McGee used the photos as references to draw panoramic images of Big City scenes. Visual Information Specialist Arya Basu then used Unity, a game engine software, to stitch the drawn images together.

“It’s like a Google Street View of the Brotherman world,” Basu says, though, for the record, the Big City map can only be accessed via the project site.

By using immersive views to build a bridge between real and imagined worlds with this story, Basu hopes readers will be able to more readily imagine themselves in the helping role of a superhero. “When I was growing up, I’d think, ‘What did Batman do?’ Every little step in the right way counts.”

Life lessons are at the core of the Brotherman stories, and Fluker and the series’ team are exploring the development of a K-12 lesson plan based on its themes. The ECDS team also hopes the digital scholarship project can spark the development of other fictional maps. “This digital platform functions as a prototype of a pedagogical tool for examining world-building techniques by fiction authors,” Fluker says.

Related Events

August 24, 2017

- Meet the Men Behind Brotherman: Revelation | August 24, 6:30-9 p.m. | Free

- An exhibition artist talk for the Unleashing the Black Imagination exhibit | August 20 – September 20

- Auburn Avenue Research Library on African American Culture and History

September 2, 2017

- Big City Maps: Using Virtual Reality to Build Fictional Worlds | September 2, 12:30-1:15 p.m. | Free

- A panel conversation with the artists and ECDS team members behind the project

- Decatur Book Festival

Related News

- Emory News Center: Inside Brotherman’s Big City

- Emory News Center: Emory hosts journalism panel to kick off Decatur Book Festival

- Emory Libraries: Emory digital team bringing streets of Brotherman to life will appear at Decatur Book Festival