Contributed to by Caitlin Brennan, Paige Hogen, Eliot Littlefield, Lauren Taylor and Kathryn Trinka

Many species produce pheromones to communicate with other members of their species. Most people think of pheromones as chemicals used to attract potential mates. However, studies have shown that insects such as butterflies, moths, and other insects produce pheromones with the opposite effect following mating (Greenfield 1981).

How could a mechanism that reduces mating have evolved? One hypothesis describes how these pheromones could have been favored due to male competition. Female Heliconius butterflies naturally release these pheromones when they are not ready to mate, but males also transfer pheromones to females during mating. This causes the female to involuntarily release the pheromone, repelling other males when she would otherwise be receptive to mating (Estrada et al. 2011).

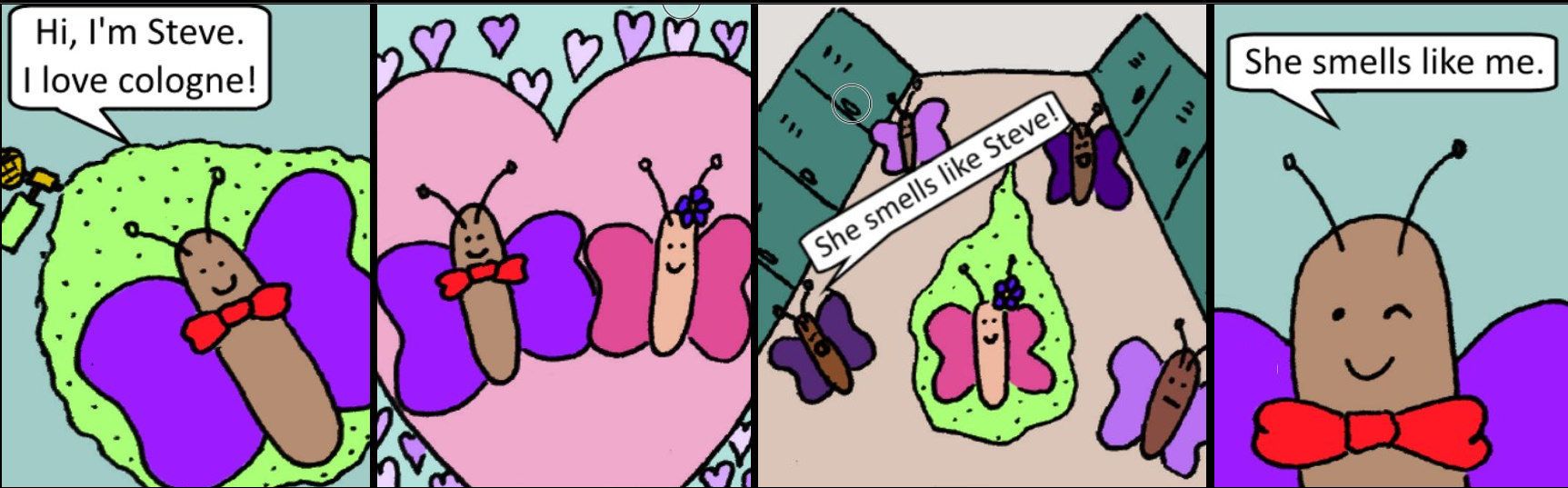

Similar to butterfly pheromones, if a guy with a lot of cologne hugs a girl, she will smell like his cologne for the rest of the day. From that point on, other guys throughout the day will be off put by her smell.

When a male green-veined white butterfly begins to court a female, she initially responds with a refusal gesture. If she is carrying repellent pheromones from another male, this posture causes her to release these pheromones. The courting male perceives her rejection more strongly than he would without the pheromones, and is less likely to continue courting her. By preventing other males from mating with the female, the first male gains a fitness advantage by ensuring that the female’s offspring are his (Andersson 2004).

Interestingly, individuals in the butterfly species Heliconius sara generally mate with only one partner, in the same way that some people eat lunch with only one person; while individuals in the species Heliconius cydno mate with many partners, just as some people might eat lunch with a huge group of people (Estrada et al. 2011). Males of the species H. sara generally have weaker pheromones because in their butterfly culture of having one single mate, there is not as much competition between males to find a mate. In contrast, males of the species H. cydno have strong pheromones, because in their butterfly culture, competition deterring other males from mating with “his girl” dramatically increases the odds that that female will produce his offspring and not somebody else’s.

For Further Reading:

Catalina Estrada, Stefan Schulz, Selma Yildizhan and Lawrence E. Gilbert. 2011. Sexual Selection Drives the Evolution of Antiaphrodisiac Pheromones in Butterflies. Evolution. Vol. 65. No. 10: pp. 2843-2854.

Johan Andersson, Anna-Karin Borg-Karlson and Christer Wiklund. 2004. Sexual Conflict and Anti-Aphrodisiac Titre in a Polyandrous Butterfly: Male Ejaculate Tailoring and Absence of Female Control. Proceedings: Biological Sciences. Vol. 271, No. 1550: pp. 1765-1770.

Ally R. Harari, Tirtza Zahavi and Denis Thiéry. 2011. Fitness Cost of Pheromone Production in Signaling Female Moths. Evolution. Vol. 65, No. 6: pp. 1572-1582

Michael D. Greenfield. Moth Sex Pheromones: An Evolutionary Perspective. 1981. The Florida Entomologist. Vol. 64, No. 1: pp. 4-17

Johan Andersson, Anna-Karin Borg-Karlson, Namphung Vongvanich, Christer Wiklund. 2007. Male sex pheromone release and female mate choice in a butterfly. Journal of Experimental Biology. 210: 964-970

Romina B. Barrozo, Christophe Gadenne, Sylvia Anton. 2010. Switching attraction to inhibition: mating-induced reversed role of sex pheromone in an insect. Journal of Experimental Biology. 213: 2933-2939