by Chloe Helsens

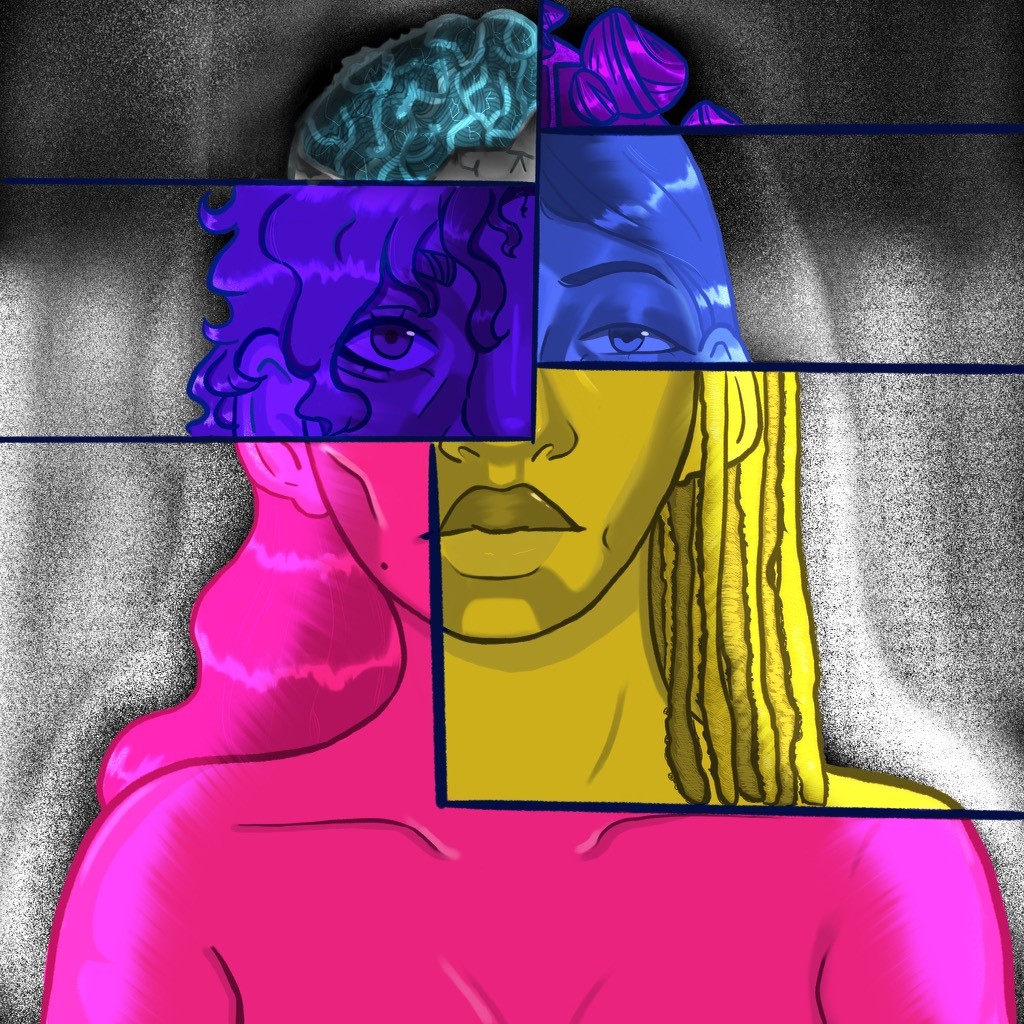

art by Owen Helsens & Kayla Barry

- What is social discrimination?

Imagine a disease, one that humans have created, is ravaging our population, and we are fallaciously withholding the cure from those who are suffering most. In a sense, that is exactly what social discrimination is: we made it, and although it’s preventable, we turned a social construct into a tangible reality within each victim’s body. Social discrimination is “the differential treatment of individuals based on their ethnicity, cultural background, social class, educational attainment, or other sociocultural distinctions” [1]. Social discrimination is rampant throughout societies around the world and is widely recognized as a type of psychological stressor, being detrimental to the mental state. Discrimination has had — and continues to have – immeasurably damaging effects on people all over the globe. Recent studies have investigated how the distress of social discrimination leads to negative physical and mental health outcomes. We will examine how a discriminatory society has forced its way into our physiological functions.

- How does social discrimination change our brains?

There are hundreds of types of discrimination that remain rampant throughout societies for centuries, yet only contemporary scientific studies have begun to recognize the severity of social discrimination’s effects on the brain. For instance, a recent 2017 study examined seventy-four adults from traditionally marginalized communities where all participants completed a self-report regarding their exposure to discrimination. They were assessed through a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scan, which measures blood flow in the brain. The fMRI scan measured participants’ amygdala activity, a region in the brain associated with emotion, and functional connectivity, which measures the interactions between two regions of the brain. The results found that individuals reporting greater incidences of discrimination were correlated with having greater amygdala activity. They also discovered increased connectivity between the amygdala and brain regions associated with the salience network, which are multiple regions in the brain that tell us which stimuli we should pay attention to [2]. The results were eye-opening because greater amygdala activity in the brain is associated with higher levels of chronic stress, and greater connectivity between the two regions “has been reported in individuals with PTSD and single-episode depression” [3]. In summary, adults from traditionally marginalized communities had neural activity reflective of extremely stressed individuals, which can lead to higher risks for chronic stress and depression. This sheds light on the evermore apparent links between social discrimination and negative neurophysiological outcomes.

Another study examining how US college students’ mental health is affected by social discrimination also found distressing results. Using data collected from the National College Health Assessment (NCHA), researchers surveyed around 417,000 college students from a myriad of universities across the US. They found that out of the 7.9% of students that experienced social discrimination in some form, there was a 37% increase in mental health symptoms and a 94% rise in the number of mental health diagnoses compared to students who reported no discriminatory experiences [4]. They also found other alarming statistics; for example, cisgender men who experienced discrimination were 210% more likely to consider suicide, 900% more likely to attempt suicide, and over 1000% more likely to self-diagnose with schizophrenia compared to cisgender men who had not experienced discrimination. High amounts of discriminatory experiences were reported most among Hispanic/Latino, African-American, Asian, and multiracial students, although Indigenous students had the highest association with poor mental health outcomes [4].

- Allostasis as a result of continual discriminatory encounters

Now that we see the abhorrent impacts that discrimination has on mental health, it is no surprise that these effects can also manifest as physiological functions. But how do we get from discrimination to disease? Only recently have scientists discovered through what means this can occur; allostatic load, or the body’s response to the cumulative burden on itself because of chronic stress [5]. One example of the effects of allostatic load on the body is shown by a 2014 study conducting a meta-analysis of the physiological impacts of racial discrimination. They found that allostatic load, the culmination of life stress and its effects on the body, can exacerbate the effects of discrimination that the body feels by leading to pathophysiology, or thwarting how the body normally functions. Symptoms can include chronic stress, metabolism changes, and increased disease vulnerability. Essentially, the greater the chronic stress associated with social discrimination, the greater the cumulative impact on their health.

Racial discrimination can also lead to the over-activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which is a feedback system in the body where different hormone pathways communicate and interact with each other; principally, it acts as our body’s primary stress response pathway [6]. This over-activation of the HPA axis produces increased levels of cortisol, a hormone commonly released as a response to stress. Chronic release of cortisol can cause “metabolic changes and effects on the immune system as well as behavioral alterations,” which connects physiological effects, such as “mood changes and cognitive impairment,” to discrimination [7]. In conclusion, social discrimination can lead to an allostatic overload, acting as the mechanism for discrimination to convert itself into diseases within the body.

Not only does discrimination affect our immune system and behavior, but it also activates a separate axis in the body that is triggered by stress, called the sympathetic-adrenal-medullary axis (SAM), that changes our cardiovascular function by increasing blood pressure, heart rate, etc [8]. The over-activation of these pathways consequently becomes a catalyst for heart conditions such as cardiovascular disease. In congruence with these findings, traditionally marginalized groups in the US, such as African Americans and Hispanics, had “chronic cardiovascular, inflammatory, and metabolic risk factors,” likely because of the discrimination they experience on a daily basis, according to Berger [9].

More recent research uncovered the fact that discrimination compromises brain matter integrity due to constant stress states. The study was conducted at Emory University with two groups consisting of both Black and White females, and investigated links between incidences of medical disorders, racial discrimination, and white matter integrity [10]. White matter enables information to be transmitted between different structures within the brain [11]. The scientists found that white matter can act as a bridge between discrimination and physiological health through chronic inflammation. Chronic inflammation damages the connectivity of white matter, which then translates to diseases such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and arthritis. Dr. Fani, along with her fellow researchers, found a pathway in which racist experiences may increase the risk for health problems via effects on select stress-sensitive brain pathways. They also linked these changes to “risk for negative health outcomes, possibly influencing regulatory behaviors.” “Now we can see that these changes may enhance the risk for negative health outcomes, possibly by influencing regulatory behaviors” [10]. Altogether, these studies expose the pathways in which discrimination harms marginalized groups, and how it thrashes its way into our physiological functions.

How much longer are we going to tolerate social discrimination within our societies? Why is it still acceptable? We continually say, in theory, we are advocates for inclusivity and social justice, yet shy away from condemning our peers, friends, or family members’ discriminatory remarks. To what extent will countless bodies pay for a sickness our society instituted? Discriminatory experiences accumulate in our bodies, eliciting both psychological and physiological consequences, while also altering stress load, white matter integrity, and even our risk for diseases. Social discrimination continues to seep its way into all facets of our world, while many of us passively watch as it rots our brains and bodies. Instead of watching as societal discrimination manifests itself into mental health disorders, diseases, and other horrifying effects, we should finally recognize and enact preventative measures against the overwhelming mental and physical burden discrimination poisons us with.