In 1975, the establishment of YongPyong Resort, the first ski resort built in South Korea, allowed for significant growth in the snow sports industry for the country.

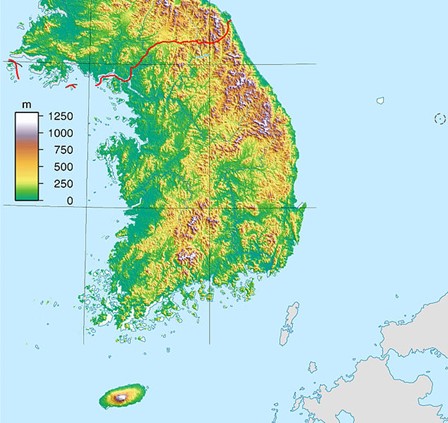

Today, there are 15 popular ski resorts in South Korea, and with the 2018 Winter Olympics being held in Pyeongchang, the small country has certainly made a big name for itself within the snow sports industry. It is hard to believe that their first ski lift was only built a few decades ago in 1975, along with the establishment of the first modern resort of its kind in South Korea, YongPyong Resort. Just one of many resorts in the PyeongChang area today, it is situated on Daegwallyeong, a moderate (832 meter) mountain pass in the Taebaek Mountain range, located along the eastern coast of the Korean Peninsula.

While entry to the leisure and recreation industry in itself was an incredibly modern step for South Korea to take, the first ski lift operating in the country was probably not very cutting-edge for the time. It is most likely that YongPyong Ski Resort’s was an older model ski lift, rather than a high-speed detachable quad lift because these did not become common in the ski industry until later, with the first high-speed detachable quad installed in the early 1980s in Breckenridge, CO. Additionally, it seems the original 1975 lift that marked YongPyong’s historic opening has since been replaced, considering the oldest chairlifts that are currently operating at YongPyong only date back as far as the late 1980s. Today, the ski resort boasts “fast chairlifts, a long conveyer belt,” and even a “gondola up Mt. Balwang.” And, in fact, Yim Seung-Hye notes in one article, this gondola is “the longest in the country,” at 7.4 kilometers.

It would seem YongPyong has been able to keep up with advancements in the ski industry enough to appeal to consumers by staying relatively modern. Though it is the country’s oldest ski resort, interestingly, it remains the largest and most favored place to ski today in Korea. Out of all the ski resorts that exist today in South Korea, YongPyong stands out for having the most ski lifts available. Additionally, the resort even hosted several of the PyeongChang Winter Olympic events on some of its 28 total slopes, including the Rainbow slope—YongPyong’s highest—which was designated as the site for the Alpine Skiing events. However, by the mid-2000s, the popularity of snow sports experienced a big boom, and along with it came the introduction of several newer resorts in South Korea. Amidst all of this, it is a wonder how the historic resort maintained its top spot.

Initially, there was just a small spot in the Daegwallyeong mountain pass that could be used to recreationally ski. While it would have been nothing like the image of a modern ski resort, simply being a bare minimum and largely untouched site, it would have been suitable for anyone seeking a no-frills skiing experience (it also would have been the only option for skiers at the time!). Ssangyang NEWS reports that the government eventually announced its desire to establish a more full-fledged “tourism complex in the 1970s,” which would effectively replace the original ski spot by introducing “a worldclass ski resort [to] the region.”

Where Did the Money Come From?

Beginning in 1973, the official “construction of Korea’s first ski resort commenced” under the newly established Yooguk Development. This “ambitious project” took a few years, especially because other facilities like an “outdoor swimming pool” were added. This was done with the hopes of making the new resort a bigger sensation. Incorporating other amenities unrelated to skiing would allow YongPyong the opportunity to remain open for the entire year, rather than just during the winter season. The idea behind this was to grant it greater potential as a business.

However, there were unforeseen downsides to this plan. One being “the popularity of leisure and recreational activities,” while growing, was unfortunately not growing “in proportion to the massive…investments” that were sunk to create the grand resort. Thus, though the idea of a resort with year-round activities had good potential in theory, it “struggled to stay afloat as a viable business” in reality. While this concept has seen great success in practice in other countries, it initially failed in South Korea due to a miscalculation of the average lifestyle of its target audience.

Within less than a decade of its formation, Yooguk Development succumbed to the financial difficulties it was facing after its overly ambitious approach to building YongPyong. So, “in December 1981, Ssangyong E&C absorbed” the business. Kim Seok Won—the president of Ssangyong Group at the time that YongPyong was developed—is still credited today. The residents of the area (anticipating the 2018 Winter Olympic Games), recognize him for “transform[ing] the Daegwallyeong area into a world-class winter sports destination.”

Although the Ssangyong Group had a large and long-lasting impact on the success of YongPyong Resort, even they eventually underwent financial hardships, as many other businesses did following the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. So, in February 2003, the company ended up selling the resort “to a local newspaper, the Segye Times,” Pyo Jae-yong reports. It was under Segye, that YongPyong Resort would “go public in the stock market,” in 2016. Journalist Park Hyong-ki notes that this was “the first time [that] a local resort” had become a public company. Since its formation, YongPyong has continued to set new precedents; going public was just one of many “firsts” the historic resort achieved.

What Role Did Politics Play in the Snow Sports Industry?

While South Korea’s President at the time of the 2018 Winter Olympics, Park Geun-hye, was involved in “corruption scandals,” as journalist Justin Bergman puts it, this is just one of the more recent examples where politics has had an effect, indirect or not, on the snow sports industry in Korea. To get a deeper understanding of the role politics has played and how it connects to ski resorts, it is necessary to go further back in South Korea’s history, around the same time that YongPyong was developed. The political and economic atmosphere of this time was much different from today but still important and relevant to this topic.

In the period following the Korean War, author Edward M. Graham describes how what is referred to as an “economic miracle” took place after 1961, when government control was taken over by the Korean military. Park Chung-hee was “the leader who emerged” during this time of authoritarian military rule in South Korea marked by the implementation of several consecutive innovative five-year plans. His recognition of the importance of having both a “strong, centralized management of the economy” and an “intense” sense of nationalism is a big part of why he was able to lead the country toward greater economic success than previous leaders. While Park may have been known for “actively suppress[ing] democracy” in South Korea, the fact that “he also placed the highest priority on improving the Korean economy” should not be forgotten.

In her book, author Yu-Min Joo shares that “Park encouraged industrialization related to rural development objectives,” which is relevant since Pyeongchang is described by the ASPRA as “a rural area surrounded by mountains.” As Joo further explains, though “Asia’s [unprecedented and rapid] urbanization is marked by the formation of mega-urban regions,” such as the South Korean city, Seoul, the impacts of these “megacities” affected the economy throughout the entire country. Due to the significant economic growth and urbanization in Seoul, the whole country benefitted. Seoul, as a “megacity,” was able to “jump-start” South Korea’s economy enough to create a solid background for which the recreation and leisure industry could thrive in more rural regions like PyeongChang, even though Seoul and PyeongChang are basically on opposite coasts of the country. In this way, urbanization in South Korea was necessary for the development of the YongPyong Ski Resort.

During the earlier years of Park’s strict rule, the government’s role was essentially to act as “entrepreneur-managers,” who would prioritize any “activities undertaken by the surging private sector.” Furthermore, Park placed a lot of importance on increasing exports, through his “export-led growth policies,” and this drive paid off, as businesses in the private sector were “achiev[ing] increasingly higher levels of export.” Until its 2016 entry into the public sector, YongPyong was a private enterprise. Armelle Solelhac writes that many “resorts are [in fact] owned entirely by private businesses.” Though South Korea most notably excelled as an exporter of textiles, tourism is categorized as part of the export sector, too. Thus, privately owned ski resorts presumably would have also been impacted by the same higher levels of export as other private enterprises.

Additionally, Park emphasized growing heavy industries in his economic strategy, viewing them as stronger and therefore more likely to help boost the economy. While the leisure and recreation industry could not really be described as a heavy one, interestingly, there is some overlap between the two industries.

An example where this can best be seen is steel, a heavy product that is widely used throughout ski resorts. In 1972, “a very large integrated steel mill” began operating in the town of Pohang. Furthermore, in 1976, after the introduction of Park’s fourth five-year plan, steel was one of the few industries that were granted continued support. Since entrepreneurs’ “choice of activity was dictated by what subsidies were available,” and steel remained a largely accessible material, they could logically establish “new sectors” based on the availability of steel. A ski resort like YongPyong Resort might have reasonably been included as one of these new sectors that business leaders in Korea were exploring due to its reliance on steel. In this way, there is an intertwined relationship between heavy industries and other industries, such as the leisure and recreation industry, that becomes very clear.

One of South Korea’s most recognizable companies, Hyundai, had primarily been a construction business, starting from the 1960s. As another example of a heavy industry, the construction business was seen as very important during this time. Likewise, YongPyong Resort was also owned by a construction company, Ssangyong Construction Company, a branch of Ssangyong Group. Once more, this connection between heavy industries that were prioritized by Park’s policies and the leisure and recreation industry that indirectly also benefitted can be seen and is evidence of how politics had an impact on the development of ski resorts, and the greater snow sports industry, in South Korea.

What Were Some Obstacles South Korea Encountered?

Unfortunately, an obstacle that many Korean companies faced upon attempting to expand into new sectors was a “lack of relevant technologies.” Because of this rational concern, “joint ventures” were permitted “between Korean firms and foreign firms that were seen as technological leaders.” Justin Bergman says that YongPyong “imported its first snow-making machine from Europe” in 1975 when the resort opened. Though there are not many details recorded about this first machine, it is necessary to consider this benchmark to be able to recognize the serious advancement Korean technology has made since. While the issue of lacking relevant technology that was a concern in the 1960s and ‘70s continued for decades, it finally started to be resolved in the early 2000s. In 2000, a company called SNOWTECH Co. was established, and their website details the fan-type machine, “SNOW ZEUS,” which became “the very first snowmaking machine ever manufactured using Korea’s own technology.” This is noteworthy considering the country had “previously entirely relied on imports,” since 1975.

What Mountain Resort Commercialization Tactics Were Used?

In order to better understand how YongPyong Ski Resort has maintained its position as a favorite resort, it is necessary to address some common marketing tactics that mountain resort brands rely on. In Armelle Solelhac’s book, she discusses the goal of any brand: to “[inspire] a feeling of enchantment, desire, or adoration, and sometimes even all three.” Solelhac then references Gallot-Lavallée, who defines the components necessary to form “this winning combination: Beauty, rarity, suspense, humor, surprise, and “the secret ingredient.” These six elements are now [also] accompanied by tourists’ increasing interest in environmental protection” among other things.

Naturally, it would take a brand a lot of trial and error to perfect this “winning combination.” YongPyong, being on the newer end of the spectrum in comparison to other world-renowned resorts, might not have all these elements “in place at once.” Nevertheless, it is clear that YongPyong at least manages to adopt the elements of beauty and rarity.

Gallot-Lavallée describes beauty as simply being “associated with the absence of threat and the presence of comfort.” On the slopes of YongPyong, Good Ski Guide notes “off-piste isn’t allowed,” and as an overall statement, “Korean resorts are decidedly family-oriented,” as Justin Bergman claimed. While thrill-seeking and danger may appeal to some snow sports enjoyers, it is evident that YongPyong can be associated with “the absence of threat,” since it is so “rule-bound” and “family-oriented,” and therefore embodies the appeal of beauty, in a sense, that is an important commercial element for the success of ski resort brands.

Solelhac portrays rarity as the act of “leading individuals to believe they risk missing out on something special.” One way that YongPyong has built up an element of rarity is by participating in the filming of K-Dramas. “For all K-Drama fans, Yongpyong Ski Resort is a must-visit spot!” Trazy Blog reports. Winter Sonata and Goblin are two popular shows that used the ski resort as a location for filming. One journal article claims that YongPyong “became an attractive winter tourism destination since the showing of” Winter Sonata, specifically with Japanese tourists. Another thing that YongPyong has going for it is that its food scene is “a unique experience,” for visitors who might be used to “burgers and fries” at other ski resorts, Jim Michaels comments. Additionally, as reported by journalist Yim Seung-hye, YongPyong’s CEO, Shin Dal-soon, thought up an innovative plan for a new project at the resort (amidst the growing crisis the pandemic brought in 2020!). His vision was to install an observatory at the very top of Mount Balwang, emphasizing his determination “to turn it into a world-famous mountain that gets visited by people from around the world all year round.” This addition to YongPyong would help further expand it from just being seen as a winter spot, and this quality only adds to the in-demand elements of rarity and exclusivity for the resort.

What about Climate Change and Environmental Concerns?

An “increasing interest in environmental protection” was addressed in Solelhac’s book, so the issue of the climate and environment at the YongPyong Ski Resort should be further examined.

The average snowfall at YongPyong is only around 250 centimeters, meaning it gets less natural snow than resorts in other countries (particularly those in its nearby rival, Japan), forcing it to rely more heavily on snow-making machines to continue operating for a proper ski season.

YongPyong Resort is situated at “higher [altitudes] than the neighboring ski resorts near Seoul Metropolitan Area.” This specific aspect of YongPyong is particularly “favorable” because of the “abundant snows and lower temperature” that it ensures. This information comes from a whole study done on The Impact of Climate Changes on Ski Industries in South Korea, focusing specifically on the YongPyong Ski Resort. This was “funded by the Korea Meteorological Administration Research and Development Program.” Since a study like this was seen as important enough to be carried out, it is evident that these issues are of increasing interest in South Korea. It is natural that tourists, especially today, would be concerned about the impact of climate change on ski resorts, as well as the impact of ski resorts on climate change when considering which ski destination to visit.

Furthermore, YongPyong Resort is in is “one of the country’s least-developed” areas, Justin Bergman writes, evoking images of natural, untouched, wilderness. Seeing as there was a great conflict surrounding the removal of trees from a “protected” area, even if it was acknowledged as a necessary procedure to prepare for hosting the Winter Olympic Games, and even if “the organizing committee [had] done damage control by promising to replant trees and return the mountainside to its natural state after the Games,” this just further proves that environmental protection is important to the South Korean public, and most likely to any potential tourists of the YongPyong Ski Resort.

Why is Differentiating South Korea from Its Neighbors Important?

In South Korea, snow sports remain primarily a leisure industry today, rather than being adopted out of necessity like for hunting or transportation. The climate study also explained that skiing “was regarded as a high class [sport] in South Korea.” This is most likely why snow sports had not been as popular there as they were in other countries, until recent decades. Then, it saw “rapid popularization” and the industry finally began to develop. The snow sports industry is seemingly still somewhat new to East Asia as a concept, though, but most notably to South Korea. As Ed Paisley wrote in 1993, Korean “people of all ages were out on the slopes trying to master a clearly new sport” at YongPyong. Moreover, in ancient China, skiing was initially necessary for hunting and survival, whereas, in modern China, skiing is simply seen as a recreational sport. It is exactly this leisure and recreation industry that is seen as a new concept in China and the rest of East Asia.

South Korea particularly struggles to establish itself as a growing force in the snow sports industry compared to Japan’s greater success and status of “ingrained ski culture,” especially due to the fact that both Japan and China have hundreds of ski resorts compared to South Korea’s meager 15. The importance of separating South Korea from other East Asian countries should be emphasized for international audiences, in order to not be seen as ignorant or disrespectful of the culture. Furthermore, the Winter Olympics are already rarely held in East Asia, occurring only four times in total.

The 2018 Winter Games, while an exciting opportunity for the spotlight it put on the country as the first and only Winter Games held in South Korea, also, unfortunately, brought along new problems that are evidence of ignorance and generalizations that Bergman details in his article. Specifically, the issue of “name recognition.” In an attempt to “avoid confusion with the North Korean capital of Pyongyang,” South Korea even went to the lengths of “officially rebrand[ing]” the host city’s original name, “Pyongchang, to PyeongChang.” Though even after taking this extra measure, “some international media” did not prioritize the adoption of the new spelling, “and travelers have still gotten confused, such as the Kenyan delegate…who accidentally booked a ticket to North Korea instead” of the South Korean ski center.

What Are the Significant Takeaways?

Through YongPyong Resort and the revolution it led for the snow sports industry in South Korea, we can see just how international the nature of skiing—and snow sports, as a whole—is. Even though South Korea may have just joined the snow sports bandwagon less than a century ago, it has certainly shown its enthusiasm since, and this would not have been possible without the creation of YongPyong Resort.

Bibliography

Baek, Ji Yeon, Eunju Lee, Gahee Oh, Yu Rang Park, Heayon Lee, Jihye Lim, Hyungchul Park, et al. “The Aging Study of Pyeongchang Rural Area (ASPRA): Findings and Perspectives for Human Aging, Frailty, and Disability.” Annals of Geriatric Medicine and Research 25, no. 3 (September 2021): 160–69. https://doi.org/10.4235/agmr.21.0100.

Bergman, Justin. “South Korea’s Olympian Winter Moment.”The New York Times, February 14, 2017, sec. Travel. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/14/travel/pyeongchang-south-korea-skiing-2018-winter-olympics.html.

Graham, Edward M. “The Miracle with a Dark Side: Korean Economic Development under Park Chung-Hee.” In Reforming Korea’s Industrial Conglomerates, 11–50. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2003. https://www.piie.com/publications/chapters_preview/341/2iie3373.pdf.

Heo, Inhye, and Seungho Lee. “The Impact of Climate Changes on Ski Industries in South Korea: In the Case of the YongPyong Ski Resort.” Journal of the Korean Geographical Society 43, no. 5 (December 2008): 715–27. https://journal.kgeography.or.kr/articles/article/GMwX/.

Johnston, Lauren. “What Winter Sports Tell Us about Population Ageing and Development: Lessons from China and Japan.” ODI, April 14, 2022. https://odi.org/en/insights/what-winter-sports-tell-us-about-population-ageing-and-development-lessons-from-china-and-japan/.

Joo, Yu-Min. MEGACITY SEOUL: Urbanization and the Development of Modern South Korea. London: Routledge, 2020.

Kim, Samuel Seongseop, Jerome Agrusa, Heesung Lee, and Kaye Chon. “Effects of Korean Television Dramas on the Flow of Japanese Tourists.” Tourism Management 28, no. 5 (October 2007): 1340–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.01.005.

Landsman, Peter. “The Lifespan of a High Speed Quad.” LIFTBLOG (blog). September 21, 2015. https://liftblog.com/2015/09/21/the-lifespan-of-a-high-speed-quad/.

Landsman, Peter. “Lifts to Look for in PyeongChang.” LIFTBLOG (blog). January 29, 2018. https://liftblog.com/2018/01/29/lifts-to-look-for-in-pyeongchang/.

Lim, Ji-Su. “Korean Town’s Quiet Olympic Bid.” Korea JoongAng Daily, January 5, 2003. https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2003/01/05/socialAffairs/Korean-towns-quiet-Olympic-bid/1900786.html.

Michaels, Jim. “Korea’s ski industry in spotlight.” USA Today, February 16, 2018. https://www.pressreader.com/usa/usa-today-us-edition/20180216/282226601195469.

Paisley, Ed. “Traveller’s Tales.” Far Eastern Economic Review 156, no. 10 (March 1993): 1.

Park, Hyung-ki. “Yongpyong Resort to finance real estate development with IPO.” The Korea Herald, May 2, 2016, sec. Business. https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20160502000760#:~:text=The%20IPO%20will%20be%20issued,for%20the%202018%20Winter%20Olympics.

“Pyeongchang’s Yongpyong Resort Has All One’s Summer Needs.” The Korea Herald, July 28, 2016. https://www.koreaherald.com/view.php?ud=20160728001092.

Pyo, Jae-Yong. “Local Newspaper Buys Yongpyong Resort.” Korea JoongAng Daily, February 13, 2003. https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2003/02/13/economy/Local-newspaper-buys-Yongpyong-Resort-/1934024.html.

Rie, Crystal. “A History of Skiing in Korea: From Bamboo Skis to the Olympic Games.” Folklife Magazine, February 23, 2018. Smithsonian Institution. https://folklife.si.edu/magazine/history-of-skiing-in-korea-from-bamboo-skis-to-the-olympic-games.

SNOWTECH Co., Ltd. “Greetings.” Accessed May 10, 2023. http://www.snowtech.co.kr/en/company/greetings/.

Solelhac, Armelle. Mountain Resort Marketing and Management. London: Routledge, 2021.

Won, Doyeon, and Sunhwan Hwang. “Factors Influencing the College Skiers and Snowboarders’ Choice of a Ski Destination in Korea: A Conjoint Study.” Managing Leisure 14, no. 1 (January 2009): 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606710802551197.

Yim, Seung-hye. “YongPyong Resort has slopes, scenery, and much, much more.” Korea JoongAng Daily, January 27, 2023. https://koreajoongangdaily.joins.com/2023/01/27/culture/foodTravel/yongpyong-resort-anifore-monopark/20230127154006275.html.

“Yongpyong.” Good Ski Guide. September 2, 2013. https://www.goodskiguide.com/yongpyong-south-korea/.

“YongPyong Resort (Dragon Valley).” Ssangyong NEWS, January 2021. http://www.ssyenc.co.kr/file/story/html/story3/V3(%EC%98%81)3Special%20Report%201.pdf. “YongPyong Ski Resort Guide: Skiing in Gwang-Do.” Trazy Blog (blog). November 16, 2022. https://blog.trazy.com/yongpyong-ski-resort-guide/.