Dublin is a city striving to retain its traditions while also embracing the new and adapting cultural and linguistic climate. An English speaker strolling through the city streets will see one familiar language and one unfamiliar language on almost every public sign, whether it be a street sign, a labeled garbage bin, or some kind of caution for nearby construction. Dublin functionally speaks English. Most of the conversations you will overhear on the bus or in line for the club will be in English. The majority of the time you will hear someone speaking a language other than English, it will be from one of the many tourist’s mouth. Businesses know the linguistic landscape of the city; most only publish their signs in English. It is redundant to include a Irish Gaelic translation, as they assume fairly correctly that no one will walking into their store speaking Gaelic but not English. However, there is a concerted effort by the local government to make sure that the Irish Gaelic language is seen to locals and visitors. Language seems to be a source of pride to the Irish people, a unique identifier of geography and tradition, a way to separate and remind all those walking around and experiencing the city that Ireland is in fact not a part of Great Britain, and that colonial rule is over.

This effort is clearly top down, similar to the way the Thai government paid businesses to have Thai signs, as described in the Leeman and Modan reading. The Irish government is taking the front foot in preserving the Gaelic language and reminding visitors and locals of an important aspect of Irish culture. In doing so, the government also evokes thoughts of more than language. When I see Gaelic, it is not just a two dimensional combination of letters on a street sign. Seeing the Gaelic text adds a sort of depth to my though in the moment; the words become three dimensional in their symbolism. When I see the Gaelic signs, I think of Gaelic football and hurling, two sports ingrained in Irish culture. I think of the Irish folk music I hear as I meander down some of the less crowded and touristy streets of Dublin. The government has taken a top down approach to making sure Dublin stands out as uniquely Irish. They want locals to be proud of their inhabitance. They want visitors to have a distinct and unmistakable mental picture of what Dublin is. So many of the cities I have visited have sort of melded into my mind as one metropolis, but Dublin is not one of them.

Dublin City street sign in both English and Irish Gaelic.

Trash bin even has Gaelic – almost all public signage has Gaelic as well as English.

The people and businesses of Dublin have taken a different approach to language. Maybe because they are satisfied with the local government’s inclusion of Gaelic in public signage, or perhaps because Gaelic is more symbolic to them than functional, almost no restaurants, pubs, shops, cafés, mobile stores, gas stations, convenience stores etc. use Gaelic in their signage. They likely see it as unnecessary. You would have a difficult time finding someone who spoke language of Ireland who does not also speak English. Instead, local businesses use the words on their signs to commodify certain areas of the city. The article we read talked about the commodification of Chinese signage in Chinatown to turn visiting Chinatown into a unique experience. They made Chinatown as more than just a physical place, but also an experience. A similar phenomenon has happened in Dublin. The temple bar district is a section of Dublin, but also an experience. When someone asks “have you been to temple bar?” they do not mean the literally district, but rather they are asking: “have you experienced temple bar?” Local shops and pubs have embraced this concept by plastering the words “Temple Bar” on every store front and small dark alley in the area. They are using the signage to magnify the Temple Bar experience, just like Chinese signage magnified and distinguished the Chinatown experience.

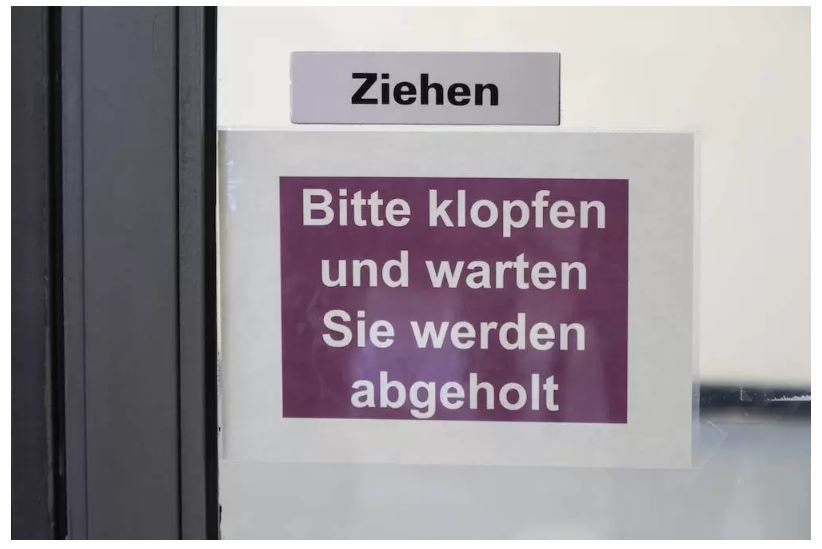

This private business just wants to get there message across, so they are functionally only using English.

While the public and private uses of signage and language are different, they do not feel in conflict. It seems that they are in tandem with each other, and build upon one another to create the complete “Dublin Experience”. The businesses trust in the local government to keep Gaelic tradition in the public view, which allows them to focusing on signage as a tool for marketing both products and places. The public and private signage blends in an aesthetic hue to create something that is uniquely Dublin.