Like every good tourist of Paris, yesterday I visited the Louvre with Kayleigh. This massive museum is home to breath taking paintings, gorgeous sculptures, and, what I feel far too many visitors pass by without notice, a wide array of different writings from thousands of years ago! I admit that a stone tablet might not look like much at first glance, but even the Code of Hammurabi had less than a handful of people taking pictures when we ran into it (and considering it wasn’t marked on the museum map, it was pure luck that we saw it at all).

My first thought upon seeing these beautiful pieces of history and writing was something very appropriate and intelligent, maybe along the lines of “this is so cool!” My second set of thoughts revolved around how it would be terrible to drop a tablet and ruin who knows how many days of work, and how my clumsiness would probably make me a terrible scribe. But eventually I got around to thinking about the written languages captured on these artifacts and how they differ so much from the alphabets I am used to. Egyptian hieroglyphics aren’t entirely made of logographs– symbols that correspond to an entire word–but there are enough to make the writing system vastly different from the English alphabet. It’s easy enough to imagine that the brain might process these writing system differently. Of course, few people are fluent in reading ancient scripts, but there is a popular language today that uses logographs: Chinese.

Previous research has found several differences in the brain regions used during reading more morpho-syllabic language like Chinese versus a more alphabetic language like English. However, these studies have mostly studied participants during artificial language tasks, such as trying to determine whether a stimulus is a real word. This task might be a convenient measure of language related brain activation for experimenters, but nobody in the real world runs around staring at scribbles and trying to decide if what they see is a real word. A 2015 study by Wang et al., on the other hand, looked at not only language use during these artificial language tasks, but also language use in a more naturalistic setting, like reading a story.

For these experiments, monolinguals in either English or Chinese took part in a naturalistic reading task or a lexical-decision task. In the first task, sixteen adults read and listened to six fairy tales in their respective language. For the lexical decision task, the participants had to determine whether the stimulus shown on a screen was a real word. In the English version, stimuli included real words, pseudowords, and non-words. The pseudowords were “almost” words made from a string of consonants, like “kybkh” or “wrgllt”. Non-words involved randomly rearranged letter strokes––a combination of lines that didn’t even form recognizable letters. Likewise, for the Chinese version, the participants had to determine between real phonograms, pseudo-characters, and artificial character-like stimuli. Unlike the phonograms, which are real Chinese characters that give information about the pronunciation and meaning of a word, pseudo-characters only superficially looked like real Chinese characters. In the artificial characters, either the position of character strokes was reversed or the strokes of a real character were randomly organized so that, like with the English nonwords, the resulting stimulus was nonsensical and completely meaningless.

The participants completed these tasks in an fMRI machine, which the experimenters used to measure brain activity. fMRIs measure a ratio of oxygenated to deoxygenated blood, and since more active areas of the brain require more oxygenated blood, fMRIs can indirectly measure brain activity. When Wang et al. looked at the resulting fMRI data for the lexical decision task. they found several differences in brain activation for Chinese versus English. For example, the Middle Frontal Gyrus (MFG) and the right Fusiform Gyrus (rFFG) show more activation for Chinese than English. Both of these brain areas may be involved in visual word processing, and the MFG may also be activated during meta-linguistic decision making. During the reading task, however, the main differences in the brain between Chinese and English readers involved the left Middle Temporal Gyrus (MTG) and visual areas that aren’t thought to be part of the brain’s reading network. According to Wang et al., these variations in activation may arise from the more visually complex nature of Chinese characters compared to English letters and the ability of certain Chinese characters to convey the meaning of a word without giving information on its pronunciation.

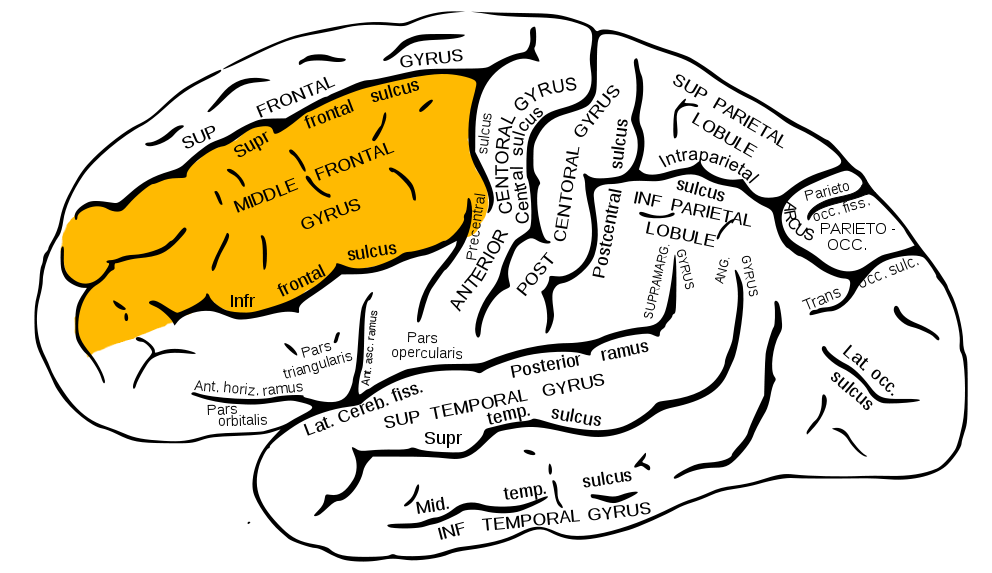

Now just where are all these brain areas I’ve listed off? Time for a mini neuroanatomy lecture! The following lovely illustrations brain give a side view of the brain, with the front of the brain towards the left and the back of the brain towards the right.

The Left Middle Frontal Gyrus

The Left Middle Temporal Gyrus

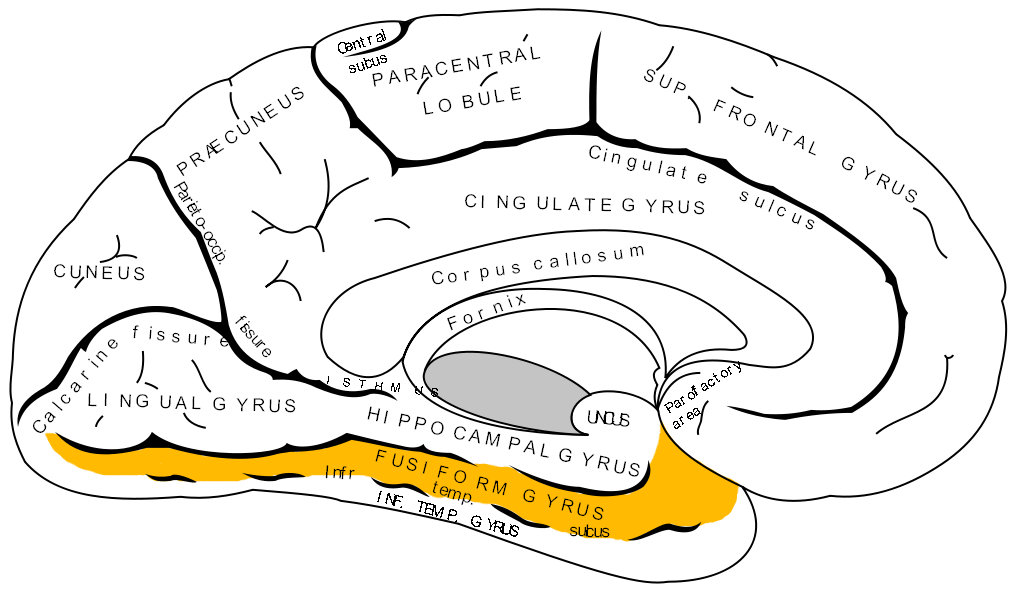

Now this next illustration of the Fusiform Gyrus is looking inside the brain, as if it were cut right down the middle between the eyes. The front of the brain is on the right side and the back of the brain is on the left.

The Right Fusiform Gyrus

So what do all of these data tell us? The gist of this study shows that the brain areas processing the Chinese writing system seem to differ slightly from the brain areas used to process English, but these differences depend on the particular language task involved. These distinctions in brain activation for the two experiments show that we can’t assume the same areas of the brain used in lab tasks like lexical decision making match the areas used in more natural tasks like story reading. Hopefully future experimenters will keep this in mind when they study language processing in the brain!

The Winged Victory of Samothrace. This statue doesn’t have much to do with writing, but she was one of my favorite things to see in the Louvre.

Exploring the Louvre was absolutely wonderful. I only wish I’d had time to see more of the artwork. With only a few days left before I leave Paris, I probably won’t get a chance to visit again during this trip, but hopefully I’ll see Paris again someday!

Bibliography

Wang X, Yang J, Yang J, Mencl WE, Shu H, Zevin JD (2015) Language differences in the brain network for reading in naturalistic story reading and lexical decision. PloS one 10:e0124388.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AGray727_fusiform_gyrus.png

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AGray726_middle_temporal_gyrus.png

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AGray726_middle_frontal_gyrus.png

One response to “Logographs and the Louvre”