Background on Beneficence

Beuchamp and Childress describe beneficence as acts of mercy and kindness to benefit another person. Benevolence refers to the character trait or virtue when acting for the benefit of others. While some acts of beneficence are not obligatory, some forms of beneficence are obligatory. Although common morality does not have a principle of beneficence that requires extreme altruism, the principle of positive beneficence supports certain obligatory rules, such as:

- Protect and defend the rights of others

- Prevent harm from occurring to others

- Remove condition that may cause harm to others

- Help people with disabilities

- Rescue people in danger

Beneficience differs from nonmalefience in that the idea is to present positive requirements of action as oppose to prohibiting negative actions, as well as not needing to be impartial or provide reasoning for these positive actions. David Hume argued that the obligation to benefit others in society comes from social interactions: “All our obligations to do good to society seem to imply something reciprocal. I receive the benefits of society and therefore ought to promote its interests.”

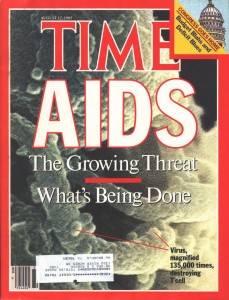

Summary of AZT Case

During placebo-controlled trials of AZT (azidothymidine) in the treatment of aids, a conflict arose over the questionable use of a placebo. In the initial trial, patients were given AZT to determine its safely. Several of these patients showed clinical improvement. On account of this, many people argued that since AIDS was fatal, everyone should be receiving AZT if it appeared to have possible positive effects. However, due to federal law regulations, more placebo trials would have to be done before pharmaceutical companies were able to produce more  of the drug. For several months, some groups of patients were given AZT and some were given placebos, and those on placebos began to die at a significantly higher rate. A data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) would be charged to consider the impact of research on future and current patients. In the AZT trial, it would have been most beneficial to stop the placebo trial early on and make more of the drug for all patients who were suffering and died early.

of the drug. For several months, some groups of patients were given AZT and some were given placebos, and those on placebos began to die at a significantly higher rate. A data and safety monitoring board (DSMB) would be charged to consider the impact of research on future and current patients. In the AZT trial, it would have been most beneficial to stop the placebo trial early on and make more of the drug for all patients who were suffering and died early.

Analysis

A great test for analyzing obligations of beneficence is found in policies of expanded access and experimental products such as medication. Beuchamp and Childress discuss whether it is morally acceptable or morally obligatory to provide an investigational product to a seriously ill patient if they cannot enroll in a clinical study. These programs are known as either “compassionate use” or “expanded access” programs. They authorize access to these investigational products even though they do not have regulatory approval. We know that the primary goal of clinical research is to provide further understanding of a product and to test its effectiveness. Thus, there is no inherent right that researchers have to distribute products that are being tested to patients, until it is proven that the treatment option works.

However, I argue that there comes a point in a clinical trail where if there is enough reasonable evidence that a product works, and may benefit patients, the drug should be an option for patients to take if they are currently taking a placebo, or even if they are not enrolled in the study. In the AZT example, patients did not have another good option at the time to help cure their AIDS, and may were dying. Whether or not the drug worked well there was enough evidence that it did something of good value, and if there was no alternative therapy available at the time I think pharmaceutical companies should have gone ahead and created more of the drug to give to suffering patients. This would have been in line with beneficence, as it would have been protecting the rights of those who wanted the best treatment option available and it would have prevented them from harm (or at least had the best chance of making them slightly improve from their condition). While I do understand the specific guidelines clinical trials must follow prior to allowing certain treatment options to become available on the market, if the primary goal of developing these treatments in the first place is to help cure patients, then if any improvement is being seen and a patient wishes to give this medication a try (if there are no other available options) then I think they should be allowed to try it. It would thus have been beneficent for AIDS patients to have been allowed to take AZT during the clinical trial.

Resources

Tom L. Beauchamp and James F. Childress, Principles of Biomedical Ethics. New York: Oxford UP, 2009. Print.

David Hume, “Of Suicide,” in Essays Moral, Political, and Literary, ed. Eugene Miller (Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Classics, 1985), pp. 577-89.

http://americanhistory.si.edu/blog/2010/09/a-brief-history-of-azt.html

I was inclined to agree with your viewpoint on this topic. It was already proven that the drug was safe, and while the evidence was not yet conclusive for its effectiveness, some evidence was present. However, stopping the clinical trial immediately after the first trial showed some effectiveness would prevent the researchers from being able to prove/test the full benefit of AZT. They would be distributing a product that they do not feel confident about. Many patients and their families might not be concerned about the lack of proof of concept, since in this case, there was not an alternative, and some argue that it is unethical to give placebos to the dying patients. However, for long-run benefit, I think it was better to continue with the placebo clinical trials until further evidence is gathered for the drug’s effectiveness before making the drug available to more patients. Widely distributing to patients concurrently with the next clinical trial would be difficult, because patients would not be likely to sign up for the clinical trial and risk getting the placebo; they would ask directly for the AZT. Of course it would be possible to observe patients who opt for the AZT versus those who opt against it, but this would fail to control for the placebo effect. Sacrificing some beneficence for the period that the clinical trials is going on would be outweighed by the beneficence resulting from conducting more thorough studies of effectiveness before widespread distribution.

I agree with the points you made and your ultimate conclusion. I personally also felt while reading this case that the ethical thing to do would have been to stop administering placebos when researchers had seen how effective the AZT was. This would have gone along with the stipulation of preventing harm to others, and removing condition that may cause harm to others. There was a reasonable amount of evidence that the treatment was working and others were benefiting while the others were dying so that should have been their cue/ indication that the treatment should be provided to all from a moral standpoint and exclusive of trial regulations and what not.