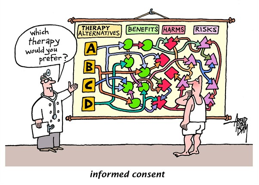

Informed consent is general information distributed to each patient. Despite the efforts made by the consent forms to notify the patient of the risks of the procedure, the content of the forms are often disregarded. The questions then rise with how detailed should the content forms be. Should the debriefing of the dangers of the procedure be mainly done by the doctor or should the information be strictly attached to the form. I believe that there should be a combination of both. The patient should be informed about the severity of their surgery through the form, and the doctor should warn the patient about the basic risks of the procedure. Although not as overlooked as Terms and Conditions, the consent forms do serve a pertinent purpose for both the patient and the doctor. The goal here is to communicate to the patient the general risks of the procedure. However, then the question is what exactly should not be shared? Should the doctor discuss the rare cases that may occur with the procedure or not? I believe that the doctor should try to translate medical terms to lamest terms, but they don’t have to go in depth on rare cases unless it is fitting to their condition. I also think that the time information is conveyed should also be a concern. They should be given enough time to contemplate whether they would like to continue with the procedure or not. The patient and doctor should both be held responsible to effectively communicate with each other their concerns with the treatment. If communication is not present then there will be a disconnect with the information given.

When thinking about how the patient is informed, we must also consider the doctor and patient relationship. Some doctors aren’t personable, but establishing a healthy connection between the doctor and patient is pertinent. When this relationship is formed, it builds trust. Also, the doctor becomes more understanding of how the patient feels generally and about the surgery. As a result, the doctor would have the patients’ best interests at heart. According to Schumann, establishing a patient doctor relationship has therapeutic purposes and is one of the main goals for a doctor during practice.

As stated in the text by Lidz there were four reasons that patients desired information: “Information of Compliance, Courtesy, Veto, and Decision making”. The reasons are understandable, and the patient has a right to this information. Some patients assume that the doctor simply knows what they’re doing, and will do what is best for them. However, Lidz made a great point that out of respect for the person patients want to be informed. The relationship between the doctor and patient would contribute to the degree of courtesy and amount of information that is disclosed. People are unique and respond differently to information when communicated. However, the patient must also question the doctor about certain issues they have. They also have a duty to ask the doctor about certain things that would affect them that the doctor may not be as informed about. The decision of the procedure should ultimately be a combination of the doctors expertise and how the patient feels. Quite naturally, there will be things that the patient does not understand about the procedure, but it is the doctor’s duty to inform the patient as much as possible with sufficient information prior to the procedure.

References

Charles W. Lidz, Ph.D., Alan Meisel, J.D., Marian Osterweis, Ph.D., Janice L. Holden, R.N., John H. Marx, Ph.D. and Mark R. Munetz, M.D. “Barriers to Informed Consent.” Arguing About Bioethics. Ed. Stephen Holland. London: Routledge, 2012. 93-104. Print.

Kegley, Jacquelyn Ann K. “Challenges to informed consent” EMBO reports, 2004. 832-836.

Suchman, Anthony L. M.D., Matthews, Dale A., “What Makes the Patient-Doctor Relationship Therapeutic? Exploring the Connexional Dimension of Medical Care”. American College of Physicians. 1988; 108; 125-130.