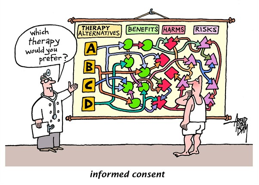

The idea of informed consent has evolved over the years along with changes in medical practice. In the past, medical care was based on paternalism, in which the doctor knew what was best for the patient. Now, medical care has become more patient-centered as reflected in the informed consent forms patients sign before medical procedures. According to the article, informed consent is when the physician is required to obtain the patient’s consent after disclosing relevant information about the treatment (Liz et al, 299). However, does that piece of document really represents its definition or does it simply represent the idea of autonomy?

Although physicians are required to disclose relevant information to patients before obtaining their consent, there are also legal standards as to what information must be disclosed. Legal standards also vary by state. For instance, “New York requires only that the practitioner provide information about reasonable foreseeable risks and alternative treatments, while the new Georgia statute requires disclosure of the nature of the treatment, any several specified risks, the likelihood of success, practical alternatives, and prognosis if treatment is declined” (Schuck, 916-917). States have already designated what physicians must disclose to patients. But does that leave the patient with any real autonomy? What if the patient would rather not be provided with the information? Or what if the patient wanted to be disclosed with all material risks?

Health care has increasingly become a legal matter. Health care providers not only have a moral duty to act in the patient’s interest, but also a legal duty. Physicians may find themselves in a court case if he or she did not follow state standards. In Arato v. Avedon, the court considered a claim made by a deceased pancreatic cancer victim’s widow and children that the physician failed to disclose information concerning the statistical life expectancy of pancreatic cancer patients, which violated their duty to obtain his informed consent. They claimed that if the patient had been properly informed of the high probability of early death, he would not have gone through painful therapies and would have avoided economic losses due to failure to put business and financial affairs into order. The court eventually ruled that there was no rule of law that mandated the disclosure of specific information like statistical life expectancy (Schuck, 917-918). This example makes me question how much influence the state has on informed consent. The law doesn’t always determine what is moral and immoral. When people think of informed consent, they usually talk about doctor-patient relationship. I think it’s important to take into consideration what the law says because it greatly affects people’s actions. In the court case discussed above, the court ruled in favor of the physician but does that mean the patient actually received all the relevant information regarding his condition? Maybe yes, maybe no.

The law plays a big part in medical practice. Not only does it tell physicians what they can and cannot do, it can also shape how people view what is considered informed consent. The law exists to protect the people. But is it too influential? Childress states that “the ideal of autonomy must be distinguished from the conditions for autonomous choice” (309). People can choose who or what to yield to when making decisions. But does real autonomy exists when the state can ultimately decide what kind of information patients can receive? Should the state be determining what is regarded as “important and relevant” information or should that be left up to the patients to decide? Can patients make a real autonomous decision when a third-party can influence what information is given?

Citations:

Childress, James F. “The Place of Autonomy in Bioethics.” Arguing about bioethics. London: Routledge, 2012. 308-316. Print.

Lidz, Charles W., Meisel, Alan, Osterweis, Marian, Holden, Janice L., Marx, John H., Munetz, Mark R. “Barriers to Informed Consent.” Arguing about bioethics. London: Routledge, 2012. 299-307. Print.

Schuck, Peter. “Rethinking Informed Consent.” The Yale Law Journal 103.4(1994): 899-959. Retrieved from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/pdfplus/797066.pdf?acceptTC=true&acceptTC=true&jpdConfirm=true.