To Be Essential & Illegal During COVID-19

“You can’t pick strawberries working remotely from home, over Zoom.”

– Oscar Londoño, head of immigrant advocacy NGO WeCount! (WLRN News, April 7, 2020)

Right now, it’s peak strawberry season in the United States. Farm workers like 73-year old Amparo Sanchez are working in the fields of California, reaping the quite literal fruits of their labor by picking and packaging each ripe strawberry with care. Looking at this picture without any context, you might even forget that we are in the midst of an unprecedented global health crisis. There are no obvious visible signs of a pandemic. Nobody in the strawberry field looks sick, nor are they wearing CDC-recommended Personal Protective Equipment, such as a mask. But after a moment, you remember… oh yes! We ARE living in a pandemic, that’s why I’m reading this at home, where I’ve been told again and again to remain until all of this is over.

You look at the picture again, a little more closely this time. Suddenly, it dawns on you that there are millions of people like the woman in the strawberry field who simply can’t stay home like you can. You might begin to wonder; why isn’t this woman wearing a mask? Does she know that masks are required in most public places these days? Is she sick, or has she been sick already? If God forbid she gets sick, are those strawberries still safe to eat? What if she can’t work anymore? Will someone else take her place? How many other farm workers are at risk during this pandemic? Whether or not you actually found yourself asking these questions before reading them, there is one very important takeaway from this picture. In these trying times, it’s easy to turn our focus inward and forget to pay attention to the very real issues faced by essential workers who are on the frontlines of this pandemic. In this blog post I will focus specifically on how coronavirus is affecting undocumented immigrant farm workers, who are currently being sent very mixed messages by the US federal government.

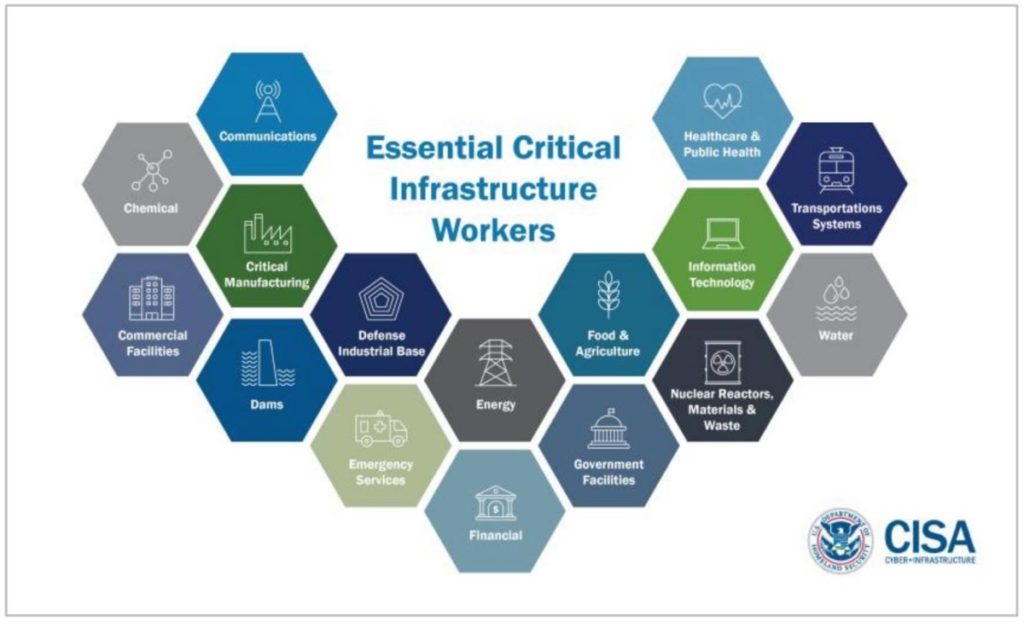

It’s no secret that undocumented immigrants are an essential part of the US farm-to-fork continuum. According to the Department of Agriculture, 50% of all crop hands in the United States are illegal immigrants. Independent growers and labor contractors estimate that figure to be closer to 75 percent (New York Times, April 10 2020). But for the duration of this pandemic every single farm worker in the US, documented or not, is considered an essential worker by the federal government. In other words, we have acknowledged as a nation that illegal immigrants are absolutely critical to the infrastructure of our food supply chain.

It’s quite ironic that after years of treating undocumented immigrants as a threat to society, the US federal government has made a 180-degree turn by labeling them as a critical part of its framework. For almost a century undocumented immigrants have been taken advantage of by US agricultural employers, deported by ICE, demonized by politicians for taking American jobs, and neglected as a group with human rights in the United States. Statistical measures of the average farm worker’s net income, access to public resources and employment benefits provide some insight as to the reality of their oppression. The Department of Labor’s National Agricultural Workers Survey in 2015-2016 found that although 33% of farmworker families live below the poverty line, most receive no help from government welfare programs such as food stamps or Medicaid. Most farmworkers are not able to take sick leave or paid vacation, and their employers seldom provide health insurance. On average, the majority of US farm workers have a 7th grade education (NAWS, 2015 & 2016).

Each one of these tragic statistics reflects how food injustice has been committed on a grand historical scale against undocumented farm workers in the United States. If you are not already familiar with the concept of food justice, look no further than philosopher Kyle Whyte. In his essay Food Justice and Collective Food Relations, Whyte provides an excellent and largely universal account of what food justice is. He breaks food justice down into two separate but equally important moral normatives, both of which must be satisfied to successfully achieve food justice. First is “the norm that everyone should have access to safe, healthy and culturally appropriate foods no matter one’s national origin, economic statuses, social identities, cultural membership or disability,” and the second norm is that “everyone who works within a food system, from restaurant servers to farm workers, should be paid livable and fair wages and work in safe conditions no matter one’s national origin, economic statuses, social identities, cultural membership, or disability” (Whyte 2015, 2). As shown in the survey results above, both moral norms have been violated repeatedly and systematically for undocumented farm workers in the United States.

In addition to committing these food injustices, the US federal government has actively interfered with these undocumented workers’ human right to collective self-determination. Collective self-determination is another term used by Whyte, referring to a human group’s right to decide their own destiny without interference from another human group (Whyte 2015, 4). The undocumented workers who make up most of our agricultural workforce still live in fear even when they are deemed essential because of how many people in their communities have been targeted and deported by ICE. But today, the American food supply chain struggles under indefinite nationwide lockdowns and restrictions in response to the coronavirus. This means that the ultimate food injustice is now being committed against these undocumented workers who are critical to our food system’s infrastructure. After so long in the shadows, they are suddenly being praised in a very untimely fashion as “heroes” essential enough to work on the frontline of this pandemic…..but not quite essential enough to guarantee that they won’t be deported. Though ICE has stated it will relax deportations for the time being, this is no guarantee of safety for the majority of the US agricultural workforce (Updated ICE statement on COVID-19, March 18 2020).

America’s agricultural industry is composed of extraordinary individuals who work labor-intensive jobs for inhumane hours: every day, every year, all year round. Together they ensure that America’s food supply remains steady, despite the fact that more than a third of them may not be able to feed their own family when they get home. As Kyle Whyte correctly points out, “groups who suffer food injustice are also often the least likely to have access to opportunities to influence key social institutions in a food system. Farm workers, minority populations and poor people, and other groups tend to have too few financial resources, and too little time and political representation” (Whyte 2015, 4). This will be especially true for undocumented farm workers in the age of coronavirus, as they are one of the few groups responsible for producing and distributing common goods across the United States and will have less time than ever to fight for equality. I can only hope that some good can become of these terrible food injustices after the dust settles. Perhaps when we finally have a moment to take a breath, sit down and think critically about the way this crisis has unfolded, we will begin to pay attention to the way our most essential personnel are treated in the United States. There is no greater time for human introspection than now, as we experience this pandemic together: one species united against a common enemy.