The Power of a Pandemic to Strengthen Racial and Economic Divides

As the coronavirus pandemic rages in the United States, so does poverty, food insecurity, and racial and economic inequality. It comes as no surprise that marginalized communities have been hit the hardest by the pandemic. The U.S. has a complex history of systematic oppression where housing and labor policies have continuously increased cyclic wealth disparity and gentrification. Continued institutional segregation brought on by housing gentrification limits access to food options for people of color and, as a result of extremely underfunded public school systems, encourages overexploited and underpaid labor particularly in the food industry. During the coronavirus pandemic, racial and economic inequity are dictating who is most at risk, who has to work, and who dies.

For the purpose of this post, I will investigate the disproportionate number of Black and immigrant lives that have been taken as a result of the coronavirus to reveal how food, race, and the pandemic intersect. Throughout this blog post I will discuss the complex web of food inequality that has resulted in disproportionate death rates for people of color and people at the front of the food supply chain.

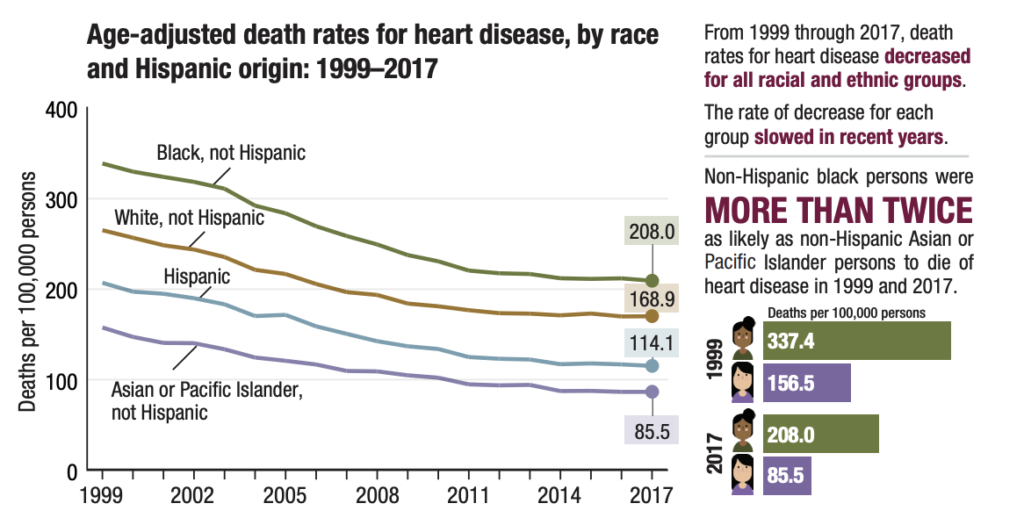

As a result of unequal access to food resources Black and Latinx Americans are at a greater risk for coronavirus. Let me begin with a few statistics regarding health related issues that contribute to one’s ability to fight off the coronavirus, many of which put Black and Hispanic Americans at a greater risk. The CDC has reported that people are at a higher risk for severe illness if they have underlying medical conditions such as heart disease, diabetes and obesity (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020). Black persons were more than twice as likely than other ethnic groups to die of heart disease in a study taken from 1999 through 2017. In a 2015-2016 study Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black adults were most likely to have obesity and were most likely to have diabetes (CDC, 2019).

These inequities in underlying health conditions are significantly correlated with unequal access to fresh, healthy food retailers for racially marginalized groups. In “Toward a Queer Crip Feminist Politics of Food,” Kim Q. Hall notes that many poor people and undocumented people who live in urban food deserts do not have access to the resources that are required to eat whole, healthy, and fresh foods. This has tragic effects on the health of people of color in the United States. According to a UCS study, “increasing the number of fresh food sources in communities of color would significantly lower diabetes rates” (Union of Concerned Scientists, 2020). Yet, even if fresh food sources in these communities were put in place, many people of color would not have the economic resources to shop there.

The coronavirus pandemic has devastated workers at the front of the food supply chain, many of whom are immigrants and African Americans. The overexploited and underpaid workers in warehouses, transportation industries, and grocery stores are not only working in unsafe conditions but are also losing their jobs at extraordinarily high rates. Kim Q. Hall references multiple works which have attempted to illuminate the unsafe and inhumane working conditions of predominantly nonwhite and immigrant workers. Many white Americans have responded to these works with concern for the purity and sanitation of their own food rather than with a concern for those who are working under unsafe conditions (Hall 2014, 184).

Hall believes that access to food requires an understanding of how exploitative working conditions are disabling non-whites and immigrants (Hall 2014, 185). All over the news we have seen grocery store workers and farm laborers die from the coronavirus due to a lack of protective measures taken to protect their health. When these workers aren’t being forced to work in unsafe conditions, they often lose their jobs and do not have the economic resources to acquire healthy food.

The coronavirus pandemic has worsened conditions for African Americans and immigrants who face disproportionately higher risks of food insecurity due to the enormous wealth gap in the United States. The majority of low-wage jobs cannot be done at home so workers in these jobs are suffering from job loss and economic instability. Workers in the leisure or hospitality industry “experience above-average rates of food insecurity (16-17%)” (Hake, 2020). In the restaurant and hotel industries which are facing shutdowns, people of color are vastly overrepresented. In addition, “Black workers often hold occupations that are less stable, such as jobs in retail and home health and jobs as nursing home aides” (Solomon & Hamilton, 2020). Kim Q. Hall notes that “shadow labor,” the work of people of color who cook and prepare foods inside and outside of the home, is the main resource of food for many class-privileged white families (Hall 2014, 182). White privileged families who have long relied on the domestication of poor people of color are being forced to order their cooks, nannies, and nurses to stay at home with no source of income. The racial disparities in the American workforce are revealed through the statistic that “16 percent of Latinx workers and 20 percent of Black workers have the ability to work from home, compared with 30 percent of white workers” (Solomon & Hamilton, 2020). Not only are Black Americans and Hispanic adults, many of whom are immigrants and many of whom are at the front of the food supply chain, at a higher risk for coronavirus due to unequal access to healthy food but they also face disproportionately higher risks of food insecurity and job loss.

Now that we are in the middle of a global pandemic, racism and racial injustice are being brought to light in unprecedented ways and it has become abundantly clear that food ethics and justice affect people’s ability to respond to a pandemic. Racial and economic disparities put people of color at the front of the food supply chain, at the bottom of the economic ladder, with an extreme lack of access to healthy food resources, and at the greatest risk for severe illness if infected with the coronavirus. The disproportionate number of Black American’s and immigrants who have low-income jobs, or who are at the front of the food supply chain risking their lives everyday are the same Americans who cannot gain access to healthy food options. If these workers lose their jobs they are faced with the enormous challenge of food insecurity. Racial and economic privilege are powerful dictators of our ability to respond to a global pandemic. Food justice and ethics during the coronavirus shed light on the racial and economic injustices that will eventually lead to a catastrophe, one that will ravish communities of color and change the way we look at racial and economic disparities in our country.