Biography

Jill Ker Conway was born in Hillston, New South Wales, Australia in 1934. She resided in the Australian outback until the death of her father in 1945. At that time, Conway, her mother, and two brothers moved to Sydney, an industrious seaport city. Conway received most of her education in the neighboring private schools and university. She graduated from the University of Sydney in 1958, after having dropped out for some time due to financial and emotional reasons. In 1960 she moved to the United States and received her PhD from Harvard University in 1969. Conway taught at the University of Toronto from 1964 to 1975, serving as Vice President from 1973 to 1975. She became the first woman president of Smith College in Massachusetts in 1975. Following Conway’s ten-year administration, she has received sixteen honorary doctorates from numerous other colleges and universities. Her success and personal definition are shaped by her childhood experiences and are detailed in her autobiography, The Road from Coorain. She is currently a visiting professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. In 2004 she was designated a Women’s History Month honoree by the National Women’s History Project.

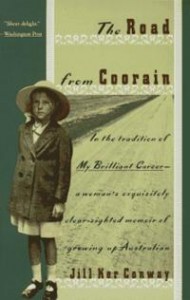

The Road from Coorain

The Road from Coorain is an account of Conway’s journey from the rural Australian outback to the urban metropolis in Australia and then to the United States. Conway describes growing up in a house, named “Coorain”(which is an aboriginal word for “windy place”), with her mother, father, and two older brothers. The family endures several hardships, including the death of her father and one of her brothers. A devastating five-year drought causes the family’s business to fail and forces the remaining members of her family to relocate to Sydney. This misfortune shapes Conway’s character and development because she learns to overcome that adversity.

Conway’s autobiography describes her intellectual development and her realization of the ways in which society suppresses women (see Gender and Nation). For instance, Conway describes her experience in applying for a prestigious trainee-ship with the Department of External Affairs (the equivalent of foreign service) while she is at the University of Sydney; she is denied a position because of her gender. She states, “I could scarcely believe that my refusal was because I was a woman” (191). In addition to gender bias, Conway addresses the irrelevance of the education the British provided during their postcolonial rule of Australia. After she visits Britain, she realizes the true beauty of the Australian landscape and credits it with being a crucial factor in defining who she is. However, she admits that the British-imposed educational system in Australia ultimately fails her when she states, “I had come to an intellectual dead end in Australia”(233). For this reason, and to escape her mother’s attempt to thwart her ambition, Conway decides to pursue her graduate studies at Harvard University in the United States.

Jill Ker Conway stated in an interview for The New York Times, that her purpose in writing is “to communicate to people very directly about the authenticity of women’s motivation for work, about how a person strives to find some creative expression. The moral of my mother’s life was that while she had challenging work, she was indomitable and when she didn’t, she fell apart. It’s very much the vogue to talk about women as developing their moral consciousness through a connectedness to mother, but I think that’s misleading. My book is deliberately a story of separation- of independence and breaking away.”

British Influence in Australia

One of the issues that elicits strong emotions in Conway is the British influence in Australia. She is considered a postcolonial writer, which raises other issues concerning the term “postcolonial.” Richard Lever and James Wieland discuss the role of post-colonialism in Australian literature in their bibliography, Postcolonial Literatures in English: “The term ‘post-colonial’–in practice often used synonymously with ‘New Literatures in English’ and ‘Third World Literatures’–emerged in the late seventies as a counter to the hegemonic and universalizing implications of the traditional categories ‘Dominion’ and ‘Commonwealth’ literature, which implicitly privilege the British imperial ‘Center’ and grant authority status to its literary and cultural traditions. Post-colonialism acknowledges, indeed insists upon, the fact that literatures of the nations and territories affected by British imperialism remain engaged with British traditions” (ix).

In Her Own Words

Jill Conway chose the autobiographical format because autobiographies provide the ability to hear “the voice” of the author. In her anthology Written by Herself, Conway states: “Autobiographies by women excite particular interest today, because three important trends in late-twentieth-century culture intersect to heighten the resonance of this form of narrative. The rise of democracy has enlarged the focus of interest in the lives of other people-from monarch, great general, and political leader to the ordinary person -someone like ourselves. And, as feminists have insisted that battles for power, authenticity, moral stature, and survival occur as fiercely within the domestic as in the public arena of life, what was once seen as placidly domestic now offers the reader a world charged with great issues.”

Selected Additional Works by Jill Ker Conway

- — A Woman’s Education. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2001.

- —“Forward.” Women on Power: Leadership Redefined. Ed. Sue J.M. Freeman, Susan C. Bourque and Christine M. Shelton. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2001.

- ––Earth, Air, Fire, Water: Humanistic Studies of the Environment. Ed. Jill Ker Conway, Kenneth Keniston and Leo Marx. Boston: University of Massachusetts, 1999.

- –– Conway, Jill Ker, Clare Munnings and Elizabeth Topham Kennan. Overnight Float. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2000.

- ––In Her Own Words: Women’s Memoirs from Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United States. New York: Vintage, 1999.

- –– When Memory Speaks. New York: Vintage, 1998.

- –– Modern Feminism: An Intellectual History. New York: Knopf, 1997.

- —. Written by Herself, Volumes I and II. New York: Vintage Books, 1995. An anthology of the ever-changing statuses of women throughout history. It provides a firsthand account by women from different cultures and time periods (1800-present).

- —. True North: A Memoir. New York: Knopf, 1994. A continuation of The Road from Coorain, this sequel traces Conway’s journey from Harvard, to her marriage, to her assumption of the presidency of Smith College in 1975.

- —. The Politics of Women’s Education. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1993. An international collection of works by women, addressing the changes that have occurred in women’s education in many countries throughout the world. The collection deals with issues women face and how they react to them.

- —. Learning About Women. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1989. A collection of works by several different writers that provide an analysis of the shifting status of women in various parts of the world.

- —. The First Generation of American Women Graduates. New York: Garland Publishing, 1987. Conway’s published thesis that she presented to the Harvard Department of History to receive her doctorate in American History.

- —. Utopian Dream or Dystopian Nightmare? Nineteenth Century Feminist Ideas About Equality. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 1987.

- —. The Female Experience in 18th and 19th Century America: A Guide to the History of American Women. New York: Garland Publishing, 1982.

- —. Women Reformers and American Culture: 1870-1930. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1971-2.

- —. ”Merchants and Merinos.” Journal and Proceedings (Royal Australian Historical Society), vol 46, part 4, 1960, pp 206-223.

- —. Modern Feminism: An Intellectual History. New York: Knopf , 1977.

Selected Bibliography

- Conway, Jill. The Road from Coorain. New York: Knopf. 1989.

- —. Learning About Women. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press. 1989.

- Heron, Kim. “Importance of Work for Women.” The New York Times Book Review. May 7, 1989. 3.

- Klinkenborg, Verlyn. “The Call of the Wind and the Kookaburra.” The New York Times Book Review. May 7, 1989. 3.

- Lever, Richard, James Wieland, and Scott Findlay. Post Colonial Literatures in English. New York: G.K. Hall & Co. 1996.

Author: Maryann Rose, Fall 1997

Last edited: May 2017