Biography

Léon-Gontran Damas was born in Cayenne, French Guiana in 1912 to a middle-class family. His father was of European and African descent and there was Amerindian and African ancestry on his mother’s side of the family. Young Damas received his primary education in Cayenne, but he later moved to Martinique and attended Lycée Schoelcher there. At Lycée, he shared philosophy classes with young Aimé Césaire, and the two started what would become a lifelong friendship.

From Martinque, Damas moved on to France where he sought higher education. As a young college student he pursued studies in law to please his parents, but he also satisfied his own interests by taking courses in anthropology and developing a keen fascination in radical politics. Once his parents heard of his new interests and activities, they cut him off financially, and Damas was forced to take on a variety of odd jobs in order to support himself. He eventually acquired a scholarship to finance his studies.

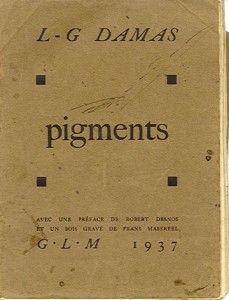

While a student in Paris he teamed up with Cesaire and Sengalese Leopold Senghor to create the foundations for what is now known as the Negritude Movement. The trio created the literary review L’etudiant noir (The Black Student), which was the forerunner of the movement, and Damas was the first of the triumvirate to publish a volume of poetry, Pigments.

Damas served briefly in the French Army in the Second World War, and like his comrades Cesaire and Senghor, he also held political office. He served in the French assembly (1945-1951) as deputy from Guiana, but was not elected for a second term. After his stint in politics he joined the French Overseas Radio Service. Damas also worked for UNESCO, traveling and lecturing widely in Africa, the USA, Haiti and Brazil. Additionally, he served as contributing editor of Prèsence Africaine, one of the most respected journals of Black studies, and as senior adviser to the Society of African Culture.

In 1970 Damas and his wife Mrs. Marietta Campos Damas, a Brazilian, moved to Washington DC. He accepted a summer teaching position at Georgetown University and also taught at Federal City College. Damas later became a professor at Howard University and was named the Acting Director of the university’s African Studies and Research Program. Damas remained at that prestigious institution and was Professor of African Literature at Howard University at the time of his death. He died in January of 1978 and was interred in his home country, French Guiana.

Damas and the Negritude Movement

In 1934, Cesaire, Senghor and Damas founded L’etudiant noir (The Black Student), a publication that aimed to break down the nationalistic barriers that had existed among Black students in France. Damas himself called L’etudiant noir “a fighting and unifying body” (Warner 13). It was greatly influenced by a previous journal called Légitime Défense, which was published in 1932 by a group of Martinican students and quickly suppressed because of the politics it espoused. L’etudiant noir picked up where this previous publication left off and expanded the focus from politics to culture. Many critics consider the creation of L’etudiant noir to be the beginning of the Negritude movement.

Damas was the first of the 3 founders of the Negritude to publish his own book of poems. This volume, Pigments, has been termed the “manifesto of the movement” (Warner 25), and every work of negritude published thereafter is said to have been influenced by it. The word “negritude” was actually coined by Cesaire and it was first published in his “Cahier d’un retour au pays natal” in 1938. The demise of L’etudiant noir in 1940 marked the end of first phase of the Negritude Movement (see also Paul Gilroy: The Black Atlantic).

Poetry

Damas’ poetry is said to differ greatly from that of the other two forerunners of the Negritude Movement. Once source declares that Damas’ “cryptic style is quite different from the ‘rich drapery’ of Senghor’s verse, or the extended explosions of Césaire’s” (Kennedy 43). His style has also been described as blunt and cryptic. It is marked by staccato rhythms, plain language, and vivid images. Some of the stylistic devices often employed in his poetry include alliteration, repetition and enumeration. An example of Damas’s writing which illustrates some of these characteristics is the following excerpt from “They Came That Night”:

How many of ME ME ME

Have died

SINCE THEN

Since they came that night when the

Tom

Tom

Rolled

From

Rhythm

To rhythm

The frenzy

Of eyes

The frenzy

Of hands

The frenzy

Of statue feet

Damas’s work is significantly influenced by the poetry of the Harlem Renaissance, the ideas of French surrealism, and the rhythms and tunes of African American blues and jazz (See African American Studies and Postcolonialism). Damas himself has also commented that in his poems one can “find rhythm” (Warner 24), that his poems “can be danced and they can be sung” (24). One critic also contends that Damas’ poetry contains many elements of Caribbean calypso such as the call/response technique, “the relating of personal experience, the ironic twists, the refrain, the tongue-in-cheek ending” (149). These features are particularly evident in one of Damas’ more popular works, “Hoquet”/ “Hicupps.” Themes that have spanned Damas’s writing include the divided self, exile and return, racial identification and solidarity, and to some extent, love.

Works by Léon-Gontran Damas

- Damas, Léon. Pigments. Paris: Guy Lévis Mano, 1937.

- —. Retour de Guyane. Paris: José Corti, 1938.

- —. Poèmes nègres sur des airs Africains. Paris: Guy Lévis Mano, 1948.

- —. Graffiti. Paris: Seghers, 1952.

- —. Black-Label. Paris: Gallimard, 1956.

- —. Nèvralgies. Paris: Présence Africaine, 1966.

- —. Veillès noires. Ottowa: Leméac, 1972.

Works Cited

- Finn, Julio. Voices of Negritude. London: Quartet Books, 1988.

- Kennedy, Ellen Conroy, ed. The Negritude Poets: An Anthology of Translations from the French. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press, 1989.

- Shapiro, Norman, ed. and trans. Négritude: Black Poetry from Africa and the Caribbean. New York: October House Inc, 1970.

- Warner, Keith Q, ed. Critical Perspectives on Leon Gontran Damas. Washington, DC: Three Continents Press, 1988.

Author: Rochelle M. Smith, Fall 2001

Last edited: May 2017

1 Comment

Leon G. Damas’s last collection of negritude poems can be found at http://www.leondamas-mine-de-rien.com/