Biography

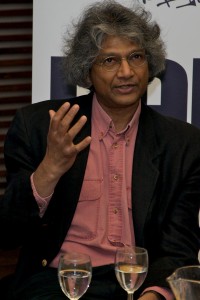

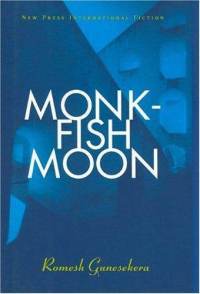

Romesh Gunesekera was born in Sri Lanka in 1954, moving to London in 1972. He grew up speaking both English and Sinhala. Gunesekera won the Liverpool College Poetry Prize in 1972, the Rathborne Prize in Philosophy in 1976, and the first prize in the Peterloo Open Poetry Competition in 1988. Gunesekera’s first book, Monkfish Moon, was a New York Times Notable Book of the Year while his first novel, Reef, was shortlisted for the 1994 Booker Prize.

Gunesekera’s first book, Monkfish Moon, is a collection of stories that provide a narrative of the political upheaval in Sri Lanka. The first story, “A House in the Country,” follows Ray, who returns to Sri Lanka from England, and Siri, Ray’s houseboy. Ray’s returns to Sri Lanka at a very confusing period in Sri Lanka’s history (See Nationalism). In the later story “Baltik,” a husband and wife find themselves struggling to keep their marriage intact. Because Nalini is Sinhalese and her husband, Tiru, is Tamil, they have relocated to London where Nalini finds her lover becoming increasingly distant as the violence at home continues to escalate. In the title story, Peter, a wealthy Sri Lankan businessman, begins to show exactly how far off course his life has moved during an awkward dinner party with family and friends” (Putnam Berkley Group Blurb). Other stories include “Captives,” “Ullswater,” “Storm Petrel,” “Ranvali,” “Carapace,” “Straw Hurts,” and “Monkfish Moon” .

Reef is Gunesekera’s first novel. It describes the childhood and adolescence of Triton, a restaurateur from Sri Lanka. Triton, after burning down a roof in his schoolyard, runs away and finds himself a servant to Mr. Salgado, a wealthy marine biologist. Under the service of Mr. Salgado, Triton grows up, becomes an expert chef, and witnesses the destruction of his country. Triton and Mr. Salgado flee to England, but ultimately, Mr. Salgado returns to Sri Lanka. Triton then must learn to live on his own.

Although Guneskera’s writings may seem to require that the reader have some background knowledge of the history, culture, and politics of Sri Lanka, Gunesekera believes that the reader can appreciate his stories with or without such knowledge. Gunesekera had this to say about his intended audience: “I think at least the kind of writing that I’m interested in doesn’t really demarcate the world in terms of this kind of reader or that kind of reader. The biggest sort of category shift you have, I think, is between people who read and people who don’t read, you know, for lots of reasons.” “Now, at the same time I do know that people who are readers also have a background and also have a physical reality, and they have a set of experiences and they bring all of those to a book when they come and therefore people who, for example, know nothing about the location, the setting of a story or a book, say, Sri Lanka. What they get out of it is going to be very different. What they get out of it is perhaps a discovery of something unfamiliar, but there is a sense of discovery they get, but if they already know the place they get something else. They also get a sense of discovery, but it’s a sense of discovery of the familiar, perhaps” (from an interview by Erney).

Gunesekera has also written The Sandglass (1998), Heaven’s Edge (2002), The Match (2006), The Prisoner of Paradise (2012), and Noon Tide Toll (2013). Much of his work deals with issues of home, the migrant experience, and their connection with time, nostalgia and loss. He is interested in the disjunctures, compressions and conflations of the past with the present, particularly as it relates to Sri Lanka and the conflicts post decolonization.

See Transnationalism and Globalism, Geography and Empire

Works Cited

- Erney, Hans-Georg. “Romesh Gunesekera.”1997. Web. Oct. 21, 1997.

- —. “‘Culture is not contained, it’s all over the place.’ An Interview with Romesh Gunesekera.” October 1997. Web. Oct. 21, 1997.

- Gunesekera, Romesh. Monkfish Moon. New York: Riverhead Books,1996.

- —. Reef. New York: Riverhead Books, 1996.

- —. The Sandglass. New York: New Press, 1998.

- Nasta Susheila. “Romesh Gunesekera”.British Council Literature, 2002. <http://literature.britishcouncil.org/romesh-gunesekera>

- The Putnam Berkley Group. “A NEW YORK TIMES Notable Book of the Year:Monkfish Moon by Romesh Gunesekera.” Web. Oct. 21, 1997.

- “REEF. Romesh Gunesekera. 1994. Granta Books. London.” Web. Oct. 21, 1997.

Selected Bibliography

- “Wild Duck”. 1994. In: Andrew Motion and Candice Rodd (eds.). New Writing 3. London: Minerva. 1994.

- “The Lover”. 1996. In: Christopher Hope and Peter Porter (eds.). New Writing 5. London: Vintage. 1996.

Related Sites

Hans-Georg Erney conducts a personal interview with Romesh Gunesekera

http://webdoc.gwdg.de/edoc/ia/eese/artic97/erney/10_97.html

Section Author: Santanu Biswas, Fall 1997

The Politics of Sri Lanka and Reef

Introduction

In the novel Reef, Romesh Gunesekera describes the lives of a Sri Lankan cook, Triton, and his master, Mister Salgado. Their lives are profoundly affected by the political turmoil surrounding the country, most notably as they flee for England in 1972. The political situation is always on the periphery of this novel. Gunesekera refers to specific historical events obliquely, and generalizes often on the state of civil war. The political history of Sri Lanka becomes vital to understanding the context of the novel. One can only understand Gunesekera’s comment that “the whole country had been turned from jungle to paradise to jungle again, as it has been even more barbarically in my own life” by understanding the history surrounding his story (25).

The Sinhalese and the Tamils

The two major ethnic (and religious) groups in Sri Lanka are the Sinhalese and Tamils, though further distinction can be made between Tamil groups. The Sinhalese are in the majority, comprising approximately 75% of the population. This group is predominantly Buddhist and speaks Sinhala. The Tamils are typically Hindu and comprise about 16% of the total population. Sometimes, this group is divided into Indian Tamils and Sri Lankan Tamils; both groups speak the language Tamil. The different languages add to the difficulties of communication and understanding between the groups. Both the Sinhalese and the Tamils have Christian minorities within their respective communities. Outside of these two major ethnic groups, Moslems also comprise a small percentage of the population. A misconception is “that the Sinhalese are (fair) Aryans and the Tamils are (dark) Dravidians, and thereby impose on Sri Lanka the famous divide in India between its “Aryan” north and “Dravidian” south, and thereby also raise the bogey of racist claims” (Tambiah 5). The idea of racial superiority exacerbates the prejudice between the two groups.

History: 1947-1971

Ceylon (Sri Lanka) became independent from Britain in 1947. Prior to this date, it was a colony of the British Empire. The first elections were held that same year. The United Nationalist Party was formed (UNP), which combined nationalist and communal parties in an umbrella group. Don Stephen Senanayake was elected Prime Minister, although he embodied no significant change from British rule upon arrival to office. Indeed, the political consensus that the government represented embraced the upper 7 percent of the population — the English-educated, Westernized elite groups that shared in the values on which the colonialist structure was founded. To the great mass of Sinhala- and Tamil-educated or illiterate people, these values appeared irrelevant and incomprehensible. The continued neglect of traditional culture as embodied in religion, language, and art forms created a gulf that divided the ruling elite from the ruled (Ara).

In the novel, Mister Salgado’s best friend, Dias, works for this government. Both men are in the elite upper group of society that is increasingly targeted by rebels in later years. In the 1956 elections, the UNP party was voted out of office in favor of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP). This party, led by S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, voted to make Sinhala the official language of the country, as well as promoting Buddhism as the state religion. Thus, it is generally accepted that the government supported Sinhalese culture over Tamil culture and tradition. In September of 1959, Bandaranaike was assassinated. His widow eventually took over his role in the government, and continued to create programs that favored the Sinhalese, such as the nationalization of private, mostly Christian, schools. In 1965, Dudley Shelton Senanayake, son of the former prime minister, came to power representing the UNP. He headed the government until 1970. In the face of increasing unemployment, inflation and the failure of state-run business ventures under the SLFP government, his government tried to restore the economy to a healthy level. However, the SLFP returned to power in 1970, again under Bandaranaike, after forming a coalition with Marxist groups. In 1972, the government officially changed the name of the country from Ceylon to Sri Lanka.

Political Unrest

In Reef, Gunesekera refers to two specific instances of political unrest: the events of 1971, which act as a catalyst for Mister Salgado and Triton to flee to England, as well as the turmoil in 1983. However, political instability had been present for decades. For example, the assassination of the prime minister in 1959, as well as the subsequent problems in finding a replacement for him, demonstrate this turmoil. Within the novel, Wijetunga, Mister Salgado’s assistant, speaks to Triton of the five precepts: “the simplified lessons that explained the crisis of capitalism, the history of social movements and the future shape of a Lankan revolution” (Gunesekera 121). These lessons sought to prove the failure of the executive leadership, as well as the assertion that the majority of citizens had not gained anything from Sri Lanka’s post-independence economic development. Moreover, the lessons strove to instruct the people on how to gain power of the country within 24 hours, using Cuba as an example. In 1971, a revolution was attempted. Sinhalese youth rose up in the “first large scale revolt against the government by youth in this country” (Tambiah 14). Although the government quickly controlled the revolt, this incident indicated the level of anger and rebellion in the population of educated, rural, young Buddhists.

The riots in 1983 started as a relatively small incident. On July 23, Sri Lankan Tamil youth, calling themselves the “Liberation Tigers,” ambushed an army truck and killed 13 Sinhalese soldiers. This attack occurred in Jaffna, which was within Tamil territory under army occupation. Then, army leaders brought the mutilated corpses into Colombo, the capital city, to display them to the people. Some Sinhalese, disgusted and horrified at the sight, went out of control. They began killing Tamils in Colombo, as well as burning houses, businesses and factories. For 3 days, this burning and pillaging continued as the president and government did nothing. On July 25 and July 27, 53 Tamil prisoners were killed within the city jail. All of these events mark the beginning of the civil war between the Tamils and Sinhalese, which officially ended in 2009. About 80,000-100,000 people have died in the 26 year war between the government and the Tamil Tigers. The Tamil Tigers were placed on the US State Department’s list of terrorist groups on Oct. 10,1997.

Selected Bibliography

- Burns, John F. “Bombing’s Fallout Adds to the Gloom Hanging Over Sri Lanka.” New York Times 17 Oct. 1997, final ed.: 7:1.

- Goonetilleke, D.C.R.A. “Sri Lanka’s ‘Ethnic’ Conflict in its Literature in English.” World Literature Today 66.3 (June 1992): 450–53.

- Gunesekera, Romesh. Reef. New York: Riverhead Books, 1996.

- Ismail, Qadri. Abiding by Sri Lanka: On Peace, Place and Postcoloniality. Minneapolis: U of Min-nesota P, 2005.

- Tambiah, S.J. Sri Lanka: Ethnic Fratricide and the Dismantling of Democracy. London: The University of Chicago, 1986.

- Wilson, A. Jeyaratnam. Politics in Sri Lanka: 1947-1973. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1974.

- “Sri Lanka.” Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 09 Apr. 2012. <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/561906/Sri-Lanka>.

- “Sri Lanka Hails Condemning of Tamil Tigers.” New York Times 10 Oct.1997, final ed: 4:3.

Author: Rebecca Makar, Fall 1997

Reef as a Bildungsroman

Bildungsroman

What is a Bildungsroman? The German word Bildungsroman means “a novel of formation,” that is, a novel of someone’s growth from childhood to maturity. Generally, a Bildungsroman is concerned with the protagonist’s development from a young person to a young adult, and the character’s need to either accept or reject the morals and customs of society. Related sub-genres focus on education and training (Erziehungsroman); artistic development (Kunstlerroman); or general growth (Entwicklungsroman).

Why is Reef a Bildungsroman?

Romesh Gunesekera’s first novel, Reef, is a moving portrayal of a boy’s growth set against the backdrop of the political and social changes taking place in his island home, Sri Lanka. In many respects, the development of Triton is a bildungsroman in which we follow the process of maturation of the main character, a Sri Lankan housekeeper.

Triton’s first experience with the social ills existent in this society is embodied in the character of Joseph. Triton states that, “Even in Mister Salgado’s house deceit had found a nest, especially in the head of his servant, Joseph” (Gunesekera 18). One afternoon, when Joseph returns home after a night out drinking, he is fired by Mister Salgado. This is a major milestone for Triton, who is now told that he will take on many of the household responsibilities.

As Triton begins to take charge of the household, he gains a new sense of confidence. He begins to place much emphasis on perfecting his cooking skills, and comes to make quite elaborate meals. The Christmas dinner is a pivotal scene for Triton in that his expertise and mastery of the art of cooking is recognized. Triton’s trip to the sea with Dias and Mr. Salgado mirrors the boy’s growing knowledge of the social changes around him. Triton states about his experience at the sea, “I felt the sea getting closer; each grain of sand closer to washing the life out of us … it made me feel helpless” (Gunesekera 70). Accordingly, the continual encroachment of the sea upon the delicate coral reef is an effective metaphor for the political and social changes effecting the island nation, and is used throughout the novel. Towards the end of the novel, Triton again remarks how, as the coral reef disappears, “there will be nothing but sea and we will all return to it” (182). Triton’s continuing maturity is highlighted in his interactions with Nili, Mr. Salgado’s lover. In Triton’s eyes, Nili treats him like a person instead of a servant, even giving him a cook book for Christmas. Interacting with Nili is Triton’s first experience speaking to women. His curiosity in going through her suitcase and setting up her room is explained in detail by the author. Triton feels that Nili’s presence in the household is a positive influence, and equates the huge changes resulting from her arrival with the changes going on in the outside world.

The last stage in Triton’s maturity begins with his departure with Mr.Salgado for London, and ends in his remaining in London by himself after Mr. Salgado returns to Sri Lanka to be with Nili. In London Triton takes classes, reads all of Mr. Salgado’s books, and ultimately learns to depend on himself. At the end of the novel, Triton has opened a successful restaurant. Clearly, his growth and maturity away from the young dependent servant to the self-sufficient man has been completed.

Works Cited

- Gordon, Neil. Boston Review 20.2. Apr. 1995. 31-2.

- Gunesekera, Romesh. Reef. New York: Riverhead Books, 1994.

Section Author: Erica Felson, Fall 1997

Last edited: May 2017

2 Comments

Too much helpful for us. Thanks a lot.

very gud