Family History

Li-Young Lee was born in Jakarta, Indonesia in 1957, the son of exiled Chinese parents. His mother came from a noble family; her father Yuan Shi-kai was the first president of the Republic of China. Lee’s father, Lee Kuo Yuan, came from a family of gangsters and entrepreneurs. Their marriage received official disapproval; moreover, Lee Kuo Yuan attached himself to a nationalist general in the Chinese civil war. During the course of the war, the general switched sides and Dr. Lee found himself in the position of personal physician to Mao Tse-tsung. This lasted for less then a year, after which the family was exiled and moved to Indonesia. There, Dr. Lee helped found a Christian college, Gamaliel University, where he taught both English and philosophy. However, the tides of politics again turned against the family as the then-dictator of Indonesia, Sukarno, began to stir up anti-Chinese feelings. This movement, combined with a few unguarded, pro-Western conversations, resulted in Dr. Lee’s arrest in 1958 and subsequent sentence to nineteen months in an Indonesian jail. After the completion of the sentence, the whole family began a second, supervised exile to Macau. However, they never reached the Indonesian government’s intended destination; instead, they were rescued from the guarded ship by an ex-student of Dr. Lee’s who brought a boat alongside the ship and spirited the family away to Hong Kong. (See Nationalism)

In Hong Kong, Dr. Lee became a hugely successful evangelist and the head of a million-dollar business. However, in the words of Lee, “He was driven almost solely by emotion and at one point got into an argument with somebody and simply left Hong Kong. We just left it all and came to America.” After a short stint as the greeter for the China exhibit at the Seattle World’s Fair, the family moved to Pittsburgh where Dr. Lee attended seminary. After graduation, Dr. Lee became a Presbyterian minister at a very small church in Vandergrift, Pennsylvania. Though read to frequently by his father, Li-Young Lee did not begin to write himself until he came to the University of Pittsburgh. There, under the guidance of Gerald Stern, he realized his passion, not just for hearing but also for creating poetry. Currently, he lives in Chicago and is one of the few full-time poets in the United States.

Lee’s Poetry

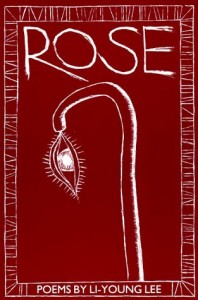

With such a background, it will come as no surprise that Lee’s poetry talks of exile, the Bible, and, most especially, the combined strength and tenderness of his father as some of its many themes. He also often uses the language of poems to create an atmosphere of silence, an atmosphere that is reminiscent of the classic Chinese poets Li Bo and Tu Fu. This may occur in part because of his own silence as a young child — it was not until the age of three that he suddenly began to speak in full sentences. Later, upon his arrival in America, he returned to silence. Feeling ashamed of his inability to speak English, he spent years playing only with other foreign children; though he could not speak their languages either, they shared the common bond from shame of speech. A poem that exemplifies this silence while displaying his father’s mixture of tenderness and austerity is “Early in the Morning” from Lee’s first book Rose. The last two verses are as follows:

My mother combs,

pulls her hair back

tight, rolls it

around two fingers, pins it

in a bun to the back of her head.

For half a hundred years she has done this.

My father likes to see it like this.

He says it is kempt.

But I know

it is because of the way

my mother’s hair falls

when she pulls the pins out.

Easily, like the curtains

when they untie them in the evening.

An Abbreviated History of China in the Early Twentieth Century

In the beginning of the twentieth century, through the influence of new industrial centers and an influx of Western missionaries, China began to feel some unrest. There was a growing awareness of the modernization occurring in the Western world and a desire for a reassertion of China’s national identity. The Qing dynasty fell, leaving several strong forces battling with each other. The one that provided the intellectual force for the revolution wanted more individualism, Western intellectualism, and an increased emphasis on science and technology. However, these intellectuals were mainly centered around the large cities and ports of China and were not trusted by the people living in the country. It was therefore mainly warlords, like Lee’s maternal grandfather, who from 1912 to 1949 inherited most of the power and ruled by force as “chauvinistic nationalists.” Some modernization did occur, but to a large extent the old order of patron-client relationships had broken down without leaving a new order to replace them. Because of this, the farmers and other country people were hugely exploited. (See Hegemony in Gramsci)

During this time of turmoil, various communist rebels moved to the country and began to stir up unrest there. Mao Tse-tsung became the Leader of the Chinese Communist party in 1931, going on to become the chairman of the People’s Republic of China from 1949 to 1959 and chairman of the party until his death. It is no wonder, therefore, that Dr. Lee, a nationalist (anti-Communist) affiliate, did not serve long as Mao Tse-tsung’s physician.

An Abbreviated History of Indonesia in the Early Twentieth Century

The future president of Indonesia, Sukarno, challenged colonialism for the first time in 1929 and was jailed for two years, after which he spent eight years in exile. During World War Two, his fortunes changed and he became the Japanese recruiter for laborers, soldiers, and prostitutes. He then pressured the Japanese for independence and on June 1, 1945, made a famous speech outlining his five principles of Indonesian nationalism: internationalism, democracy, social prosperity, and belief in God. On August 17, he declared Indonesia’s independence and became the first president of the new Republic. The Dutch, meanwhile, did not grant formal independence until 1949.

During the years that followed, while the country did attain a growing sense of “national identity” following the advent of better health care and education, Sukarno himself indulged in wilder and wilder extravagances. In 1956, the parliamentary system was dismantled and Sukarno declared himself the head of a new “Guided Democracy” and “Guided Economy.” Assassination attempts grew more frequent as his cabinet of 100 corrupt ministers became infamous, yet he was still able to engage the nationalistic feelings of the Indonesians in 1965. However, later in 1965, Sukarno arranged a coup that killed his enemies and declared a new revolutionary regime. At this time, another man stepped in, General Suharto, and reversed the coup, taking over Sukarno’s power at the same time. Again, it is easy to see why Sukarno might imprison Dr. Lee for his Western leanings and Christian teachings.

Books by Li-Young Lee

- Lee, Li-Young. The City in Which I Love You. Brockport, N.Y.: BOA Editions, 1990.

- —. Rose. Brockport, N.Y.: BOA Editions, 1986.

- —. The Winged Seed, A Rememberance. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

- —. Book of My Nights. Rochester: BOA Editions Limited, 2001.

- —. Behind My Eyes. New Work: W.W. Norton, 2008.

Works Cited

- “China.” CIA Factbook. Web.

- “East Asian People.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Web.

- “Indonesia.” CIA Factbook. Web.

- “Mao Zedong.” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Web.

- Miller, Matt. “Darkness Visable: Li-Young Lee Lights Up His Family’s Murky Past With Poetry.” Far Eastern Economic Review (30 May): 34-36.

- Moyers, Bill. “Li-Young Lee.” The Language of Life: A Festival of Poets. New York: Doubleday, 1995.

- Muske, Carol. “Sons, Lovers, Immigrant Souls.” New York Times Book Review (27 Jan. 1991): 7.

- “Sukarno” Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Web.

- Xiaojing, Zhou. “Inheritance and Invention in Li-Young Lee’s Poetry.” MELUS. Spring 1996: 113-32.

Selected Bibliography

- “Award-Winning Poet Talks About His First Book of Prose.” Radio Program: Weekend Edition-Sunday—NPR. 26 Mar, 1995.

- Hesford, Walter A. “The City in Which I Love You: Li-Young Lee’s Excellent Song.” Christianity and Literature (Autumn 1996): 37-60.

- Huang, Yibling. “The Winged Seed: A Rememberance.” Amerasia Journal (Summer 1998): 189-191.

- Lynch, Doris. “Arts & Humanities—Poetry: The City in Which I Love You.” Library Journals (1 Sept., 1990).

Author: Hannah Fischer, Fall 2000.

Last edited: May 2017

1 Comment

nice article…