“Reading Portis is one of the great pure pleasures – both visceral and cerebral – available in modern American literature” (Rosenbaum 33).

Biography

Charles Portis was born on December 28, 1933 in El Dorado, Arkansas. His father, Samuel, was a public school superintendent, while his mother, Alice Waddell, was an adamant supporter of the literary arts. Portis joined the Marine Corps following his graduation from school, serving from 1952 to 1955. During this time he rose to the rank of sergeant, and following his discharge he received a degree in journalism from the University of Arkansas. He worked as a reporter for several publications, including the Commercial Appeal in Memphis, the Herald Tribune in New York, and the Arkansas Gazette in Little Rock. His position at the Herald Tribune enabled him to interact with journalists such as Dick Schaap, Jimmy Breslin, and Tom Wolfe. The paper promoted him to the position of London correspondent, but he returned to Arkansas shortly thereafter to pursue a career in fictional literature (Idol 361; Colby 697; Magill 1665).

Style

Charles Portis has been described as “one of the most inventively comic writers of western fiction. With an unerring ear for the rhythms of speech and idiosyncrasies of language, he delivers deadpan humor as his characters strive to come to terms with their own limitations and an increasingly cockeyed world” (Cleary 610). He utilizes the effectiveness of humor to define various components of the American character and its spirit. Most often, the characters in his novels novels are Arkies (or residents of Arkansas), and he “takes the cliche of the Arkansas Traveler and stands it on its head” by giving them a broad range of adventures in “a bewildering, and sometimes dangerous, world” (Magill 1667). His novels depict a “clash between the temperaments and values of the old and new South and between traditional Southern traits such as independence and gentility and the untamed, willful quality of the Southwest” (Connaughton 264).

Themes

The primary theme of Portis’ novels is that of conflict between his characters’ desire for travel and adventure and their attraction to the comforts of home and daily routine (Idol 361). A restless disposition is linked to this impasse. Portis “shows that restlessness has its moments of both high humor and profound sadness. He presents this restlessness as a trait of Americans, as well as a universal fact of man’s existence” (Idol 362). Revenge is another motif interwoven throughout his narratives. Portis frequently illustrates the notion of the victim as being treated unfairly by the abuser and that a great injustice has been performed. This is linked to the theme of justice that is present in every aspect of his writing” (Idol 363). Connaughton argues that Portis “is not so much a writer of vision as of observation” and that he is able to select “appropriate actions and descriptive details and constructs sustained, idiomatic voices for his characters, all of whom exhibit a basically good-natured, if slightly askew, view of the world”(267).

The Master of American Dialects

Charles Portis has a gift for representing American dialects, particular Southern ones. His use of dialect allows the novel to explore “how some Americans practice deceit and hypocrisy and try to conceal their inhumanity to man” because they present “slick, hustling, fast-talking characters capable of everything from spreading soulbutter to cranking out position papers for aspiring politicians [who] prey on the innocence, trust, and piety of Portis’ good-hearted people” (Idol 364).

Works By Portis

- Portis. Charles. “I Don’t Talk Service No More.” The Atlantic Monthly, May 1996.

- —. “The New Sound from Nashville.” Saturday Evening Post (February 12, 1966): 30.

- —. “Traveling Light.” Saturday Evening Post (June 18, 1966): 48.

- —. The Dog of the South. New York: Knopf, 1979.

- —. Gringos. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1991.

- —. Masters of Atlantis. New York: Knopf, 1985.

- —. Norwood. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966.

- —. True Grit. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1968.

Brief synopses of the novels

Norwood

A crazy tale of Norwood Pratt, an ex-Marine, from Ralph, Texas. The itch to leave this tiny town takes hold, and so Norwood drives to New York City chasing Marine friend who owes him $70, opening the door for many adventures and the entrance of unique individuals along the way.

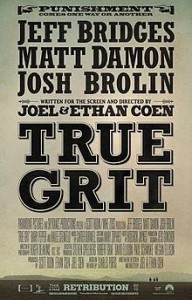

True Grit

Probably Portis’ most well-known novel depicting Mattie Ross’ quest for revenge of her father’s murder. She chases their farmhand, Tom Chaney, who committed the crime, across the Indian Territory. Mattie is accompanied by fat, drunk, middle-aged U.S. Deputy Reuben J. “Rooster” Cogburn and Texas Ranger LaBoeuf in her pursuit of Chaney and Lucky Ned Pepper’s gang. This novel was adapted into two award-winning films in 1969 and 2010.

The Dog of the South

A tale of a man’s quest for his stolen car taken by his wife who has left to join her first husband. Ray Midge follows the paper trail left by his wife, Norma, and her partner on her journey, Guy Dupree, to Texas, Mexico, and, finally, to Honduras, encountering a fair share of odd characters along the way.

Masters of Atlantis

Portis illustrates how a secret society “founded by a con artist and his gullible dupe comes to be a source of genuine meaning and faith for half a century of devotees (with the suggestion that all secret societies pretending to esoteric knowledge, from Skull and Bones to the Masons to the CIA, are all the products of collective self-delusions)” (Rosenbaum 32).

Gringos

Portis takes us on a journey searching for the Inaccessible Lost City of Dawn “that draws, like a magnet, all the lonely and dispossessed, the mad romantics and con artists of the States” to uncover the missing aspects of their lives in the Mayan rain forests (Rosenbaum 33).

Selected Bibliography

- Ditsky, John. “True Grit and ‘True Grit,’” Ariel 4.2 (1973): 18-31.

- Shuman, R. Baird. “Portis’ True Grit: An Adventure or Entwicklungsroman,” English Journal 59 (1970): 367-370.

- Wolfe, Tom. The New Journalism. New York: Harper, 1973.

Works Cited

- Cleary, Michael. “Charles Portis,” Twentieth Century Western Writers. Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1982.

- Colby, Vineta (ed). World Authors 1980-1985. New York: The H.W. Wilson Company, 1991.

- Connaughton, Michael E. “Charles Portis,” Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 6: American Novelists Since World War Two, second series. Detroit: Gale Research Company, 1980.

- Idol, John L. “Charles [McColl] Portis,” Contemporary Fiction Writers of the South: A Bio-Bibliographical Sourcebook. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press, 1993.

- Magill, Frank N. Magill’s Survey of American Literature,Volume 5. New York: Marshall Cavendish Corporation, 1991.

- Rosenbaum, Ron. “Our Least-Known Great Novelist,” Esquire 129.1 (1998): 30.

Related Links

“I Don’t Talk Service No More,” Charles Portis’ short story about an ex-Marine

http://www.theatlantic.com/issues/96may/9605fict/9605fict.htm

Author: Vered Kleinberger, Spring 1999

Last edited: May 2017

1 Comment

Pingback: True Grit by Charles Portis – Fiction Database