Biography

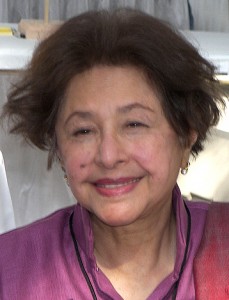

Bapsi Sidhwa is Pakistan’s leading diasporic writer. She has produced four novels in English that reflect her personal experience of the Indian subcontinent’s Partition, abuse against women, immigration to the US, and membership in the Parsi/Zoroastrian community. Born on August 11, 1938 in Karachi, in what is now Pakistan, and migrating shortly thereafter to Lahore, Bapsi Sidhwa witnessed the bloody Partition of the Indian Subcontinent as a young child in 1947. Growing up with polio, she was educated at home until age 15, reading extensively. She then went on to receive a BA from Kinnaird College for Women in Lahore. At nineteen, Sidhwa had married and soon after gave birth to the first of her three children. The responsibilities of a family led her to conceal her literary prowess. She says, “Whenever there was a bridge game, I’d sneak off and write. But now that I’ve been published, a whole world has opened up for me” (Graeber). For many years, though, she says, “I was told that Pakistan was too remote in time and place for Americans or the British to identify with” (Hower 299). During this time she was an active women’s rights spokesperson, representing Pakistan in the Asian Women’s Congress of 1975. (See Gender and Nation)

After receiving countless rejections for her first and second novels, The Bride and The Crow Eaters, she decided to publish The Crow Eaters in Pakistan privately. Though the experience was one she says, “I would not wish on anyone,” it marks the beginning of her literary fame (Sidhwa “Interview” 295). Since then, she has received numerous awards and honorary professorships for these first two works and her two most recent novels, Cracking India and An American Brat. These include the Pakistan National honors of the Patras Bokhri award for The Bride in 1985 and the highest honor in the arts, the Sitari-I-Imtiazin 1991. Her third novel, Cracking India was awarded the German Literaturepreis and a nomination for Notable Book of the Year from the American Library Association, and was mentioned as a New York Times “Notable Book of the Year,” all in 1991. A Bunting Fellowship from Harvard and a National Endowment of the Arts grant in 1986 and 1987 supported the completion of Cracking India. She was awarded a $100,000 grant as the recipient of the Lila Wallace-Reader’s Digest Award in 1993. Her works have now been translated into Russian, French and German. She has also taught college-level English courses at St. Thomas University, Rice University, Mt. Holyoke, and The University of Texas as well as at the graduate level at Columbia University, NY.

Parsi/Zoroastrianism

What is most remarkable about Bapsi Sidhwa’s perspective on the Partition of the Indian Subcontinent is her religious distance from its most immediate effects as a member of the Parsi/Zoroastrian community. The traditional story of the Parsees’ arrival from Iran to India in the 8th century C.E., in which an Indian prince sent Zoroastrian refugees fleeing Islamic expansion a messenger with a glass of milk, signifying that the Indian people were a united and homogenous mixture that should not be tampered with. In response, the Parsees dropped a lump of sugar in the milk, saying that they would blend in easily and make the culture sweeter. It followed that they were granted a home in India because Parsees neither proselytized nor entered into politics. Thus, Bapsi Sidhwa’s heritage allowed her to witness the Partition from a safe distance, since Parsees held a religiously and politically neutral position. In an interview she says, “The struggle was between the Hindus and the Muslims, and as a Parsee (member of a Zoroastrian sect), I felt I could give a dispassionate account of this huge, momentous struggle” (Gutman).

Zoroastrianism’s origins go back to 3000 BCE among the Proto Indo-Iranians. These people inhabited the South Russian Steppes, east of the Volga River. Recognizing the cyclical nature of reality in day and night and the seasons, the Proto Indo-Iranians looked to the sky, land, and water for divinity. However, the discovery of bronze casting around 2000 BCE caused many of these peaceful shepherds to abandon their flocks and become warriors. Zarathustra was born into this society around 1500 BCE. After meditating for several years, he arrived at conversation with one God, Ahura Mazda, “The Lord of Light.” Thus, Zoroastrianism is one of the earliest monotheistic religions. Zarathustra took his dialogues with Ahura Mazda and composed hymns from them called The Gathas. He sung of a God who was all-knowing, beyond idolatry, and active in the present. Drawing on his people’s past, Zarathustra taught that Ahura Mazda’s power is revealed through the precise laws of the universe (Asha). Furthermore, it is believed that Ahura Mazda gave humans the divine gift of the mind (“Voho Manoh”) to recognize their God.

The major tenets of Zoroastrianism surround death and marriage. Dakhma-nashini is the only method accepted for disposing of the dead’s body. The corpse is placed in a stone Dakhma, open to the sky and birds of prey. The body enters the food chain just as any other dead animal or plant does, again emphasizing the life cycle. Dakhma-nashini also ensures that the water supply will not be contaminated. Marriage outside the religion is forbidden as is conversion to preserve ethnic identity and tradition. For the Zoroastrians/Parsees, ethnicity and religion are the same. Bapsi Sidhwa addresses the strain put on the Parsee community as the world becomes increasingly connected in her most recent novel, An American Brat. Presently, the Parsee community numbers about 1 million worldwide. They are generally Anglicized and well educated.

The Faravahar is the sacred figure of Zoroastrianism. It symbolizes the soul’s journey through life and eventual union with Ahura Mazda with the aid of the mind. The belief of the soul’s absolute importance in existence is symbolized by the profile of the man placed in the center of the Faravahar. The soul progresses through its life journey on two outreaching wings. Each wing has five layers of feathers which correlate with the five senses, the five Gathas of Zarathustra, and the five Zoroastrian divisions of the day (Gehs). The two curving legs extending from the male profile’s ship symbolize the two opposing paths of good and evil each soul must navigate consciously. The feathered tail that dips between these two legs represents the rudder of the soul. It has three feather layers for Humata (Good Thoughts), Hukhta (Good Works), and Hvarasta (Good Deeds). The circular ring that the man holds within his hands calls Zoroastrians to remember the cycles of death and birth, success and failure, rebirth, and alternate realms of existence beyond this reality.

Cracking India

In her third novel, Cracking India, Bapsi Sidhwa delicately threads the story of an 8 year old girl named Lenny with the din of violence ready to crash around her world as the Partition moves from political planning into reality. The story is told in the present tense as the events unfold before the young girl’s eyes, though moments of an older Lenny looking back are apparent. Like Sidhwa, Lenny is stricken with polio, lives in Lahore, and is a Parsi. She is clever and extremely observant narrator, though many times her understanding is limited by her young age. This naïveté is apparent when she ponders if the earth will bleed when the adults “crack” India. The historical scene of the Partition is integrated well into the novel through Lenny’s young eyes, though Sidhwa is criticized by some critics for making Lenny’s character too intelligent for her age. As Lenny becomes more aware, she must confront a reality increasingly reduced into categories and labels.

The characters that surround Lenny include “Slave sister,” “Electric Aunt,” “Old Husband,” “Godmother,” “Ayah,” and “Ice-Candy-Man.” Initially, the novel took the name of this last character. However, publishers feared that an American audience might mistake the unfamiliar name for a drug pusher. In fact, the Ice-Candy-Man is a Muslim street vendor drawn like many other men by the magnetic beauty of Ayah, Lenny’s nanny. Lenny observes the transition of the Ice-Candy-Man through the roles of ice cream vendor, bird seller, cosmic connector to Allah via telephone, and pimp. This last role shows the devious methods which some, particularly politicians, will sink to in order to survive. Of the dirtiness of politics, Bapsi Sidhwa says, “As a Parsee, I can see things objectively. I see all the common people suffering while the politicians on either side have the fun” (“Writer-In-Residence”). In contrast, Sidhwa presents us with the Godmother as a truer source of strength and action, through knowledge instead of pride and rhetoric.

Along with political ineffectiveness, Sidhwa draws out the most damaging effect of the Partition, the symbolic desecration of women on both sides of the conflict. Sidhwa recalls the chilling shrieks and moans of recovered women at the time. She asked herself, “Why do they cry like that? Because they are delivering unwanted babies, I’m told, or reliving hideous memories. Thousands of women were kidnapped” (Sidhwa “New Neighbors”). Elsewhere, she continues, “Victory is celebrated on a woman’s body, vengeance is taken on a woman’s body. That’s very much the way things are, particularly in my part of the world” (Graeber). Cracking India includes among all of this tragedy a brilliant sense of humor as well. She explains, “Laughter does so many things for us. It has the quality of exposing wrongs and gets rid of anger and excitement” (“Writer-In-Residence”). Cracking India calls to recollection the pain of old, caked wounds so that they may finally be healed.

Sidwa has a strong creative partnership with Pakistani/Canadian director, Deepa Mehta, with Sidwa involved in two of the three films in Mehta’s film trilogy, Fire, Earth and Water.

Works Cited

- Graeber, Laurel. “The Seeds of Partition.” Review of Cracking India. New York Times Book Review 6 Oct. 1991.

- Gutman, Ruth. “Visiting Prof’s Novel to be in Film.” (27 Feb. 1997) The Mount Holyoke News.

- Hower, Edward. “Ties That Bind.” The World & I. Mar. 1994: 297-301.

- Sidhwa, Bapsi. “Interview with Bapsi Sidhwa.” The World & I. By Fawzia Afzal-Khan. Mar. 1994: 294-295.

- —.”New Neighbors.” (11 Aug. 1997) Time.

- “Writer-in-Residence Bapsi Sidhwa Takes Laughter Seriously.” (28 Mar.1997) The College Street Journal. 2 Apr. 1997. Web. http://www.mtholyoke.edu/offices/comm/csj/970328/sidhwa.html

Bibliography of Related Sources

- Bamji, Soli S.”Zoroastrian Religion.” Soli’s Home Page. 2 Apr. 1997. Web. <http://www3.sympatico.ca/zoroastrian>

- Havewalla, Poris Hami. “Traditional Zoroastrianism: Tenets of the Religion.” (12 Jun. 1995)

- Joshi, Namrata. “The Fire Within.” India Today International. 23 Mar. 1988: 24d-24e.

- Neku, Dr. H.P.B. “The Significance of the Faravahar/Farohar Figure.” (18 Jan. 1997) The Stanford University Zoroastrian Group

- Ross, Robert. “Revisiting Partition.” The World & I. Jun. 1992: 369-375.

- Sidhwa, Bapsi. An American Brat. Minneapolis: Milkweed, 1993.

- —. Cracking India. Minneapolis: Milkweed, 1991.

- —. The Crow Eaters. Minneapolis: Milkweed, 1992.

- —. “Interview with Bapsi Sidhwa” (with Fawzia Afzal-Khan). The World & I. Mar, 1994: 294-295.

- —. “New Neighbors.” (11 Aug. 1997) Time.

- —. The Pakistani Bride. New York: Penguin, 1990.

- Tharoor, Shashi. “Life with Electric-Aunt and Slave sister.” Rev. of Cracking India. New York Times Book Review. 6 Oct. 1991.

Related Sites

Author Website

http://www.bapsisidhwa.com/

Author: Jay Wilder, Spring 1998

Last edited: May 2017